Nelson: Britannia's God of War (8 page)

Read Nelson: Britannia's God of War Online

Authors: Andrew Lambert

Though Nelson had gone to the West Indies with the backing of the two most important men in the service, his privileged access to Howe and relationship with Hood did not translate into close personal contact. Hood, the closer of the two, did not correspond with him while in the West Indies, and made his views on the Prince William affair clear by distancing himself from Nelson and bringing Schomberg into his own ship. Nelson banked on William becoming admiral, so that he could command one of the ships in his line of battle. His letters to the Prince were both prescient and shameless in their flattery: ‘It is only by commanding a Fleet which will establish your fame, make you the darling of the Nation, and hand down your Name with honour and glory to posterity.’ The same letter even requested a household appointment for Fanny.

24

In 1790 a fleet was mobilised for a possible war with Spain. Despite William’s intervention with Chatham Nelson was ignored.

25

It was obvious to everyone but Nelson that the Prince had no influence. Nor did Hood do anything for Nelson in 1790, or in 1791 when he commanded the mobilisation aimed at Russia. Even in 1793 he remained distant. Nelson had abandoned Hood’s school for William’s entourage, exchanging duty and honour for the coat-tails of a loose-living, hard-drinking lightweight. Had William gone on to better things − and Nelson beleived he could have been a useful flag officer – his move would have seemed astute. In the event, though, it was another royal who rescued Nelson from the unemployed list: his name was Louis, and he had recently lost his head.

CHAPTER II

1

Goodwin, pp. 106–13

2

Goodwin, pp. 113–17 lists the offences, and the number of lashes awarded.

3

According to his first lieutenant James Wallis, who retailed the story to C&M [1840] p. 143. There is a complete transcript of this memo taken from Add. 34,990 in Rawson ed.

Nelson’s

Letters

from

the

Leeward

Islands

, pp. 47–54. Pocock,

Young

Nelson,

p.

194

4

Ritcheson,

Aftermath

of

Revolution:

British

Policy

Towards

the

United

States,

1783

–

1795

, PP. 3–17, 218–21

5

His letters to William frequently refer to this fraud. See 29.12.1786; Nicolas I p. 204

6

Nelson to William Nelson 29.3. and 2.4.1784: Nicolas I p. 101–2

7

Brewer,

The

Sinews

of

Power:

War,

Money

and

the

English

State

1688

–

1783,

pp. 101–5

8

Ehrman,

The

Younger

Pitt:

The

Years

of

Acclaim

. Nelson to Suckling 14.1.1784: Nicolas II, pp. 479–80

9

Nelson to Hughes January 1785, and copied to the Secretary to the Admiralty 18.1.1785: Nicolas I pp. 114–18

10

Rawson ed.

Nelson’s

Letters

from

the

Leeward

Islands

, pp. 23–40

11

Nelson to Suckling 25.9. and 14.11.1785; Nicolas I pp. 140–6

12

Nelson to Locker 5.3.1786; Nicolas I pp. 156–60

13

Nelson to Moutray 6.2.1785 and Nelson to Admiralty 17.2.1785; Nicolas I pp. 118–19, 121–3

14

Fanny’s letters to him were burnt on the eve of the attack on Tenerife.

15

Nelson to Fanny 4.5.1786; Nicolas I p. 167. Vincent notes at p. 71 that this was still being used as a homily for young naval officers in 1954.

16

Nelson to Fanny 6.3.1787; Naish ed.

Nelson’s

Letters

to

His

Wife

and

Other

Documents,

1785

–

1831

,

p. 50

17

William to Hood 9.2.1787: Ranft, ed. ‘Prince William and Lieutenant Schomberg’, in Lloyd, ed.

The

Naval

Miscellany:

Vol.

IV.

London, 1952 pp. 270–2

18

William to Nelson 3.12.1787 and William to Hood 26.12.1787 and 5.1.1788; Ranft pp. 286–95

19

Howe to Hood 2.7.1787; Ranft p. 287

20

Rose recalled this meeting in conversation with Clarke or McArthur. See C&M (1840) I p. 150

21

Nelson to Clarence 10.12.1792; Nicolas I pp. 294–7

22

Ziegler,

King

William

IV

, pp. 37–95, for Prince William’s relationship with Nelson and the Navy.

23

Clarence to Nelson 3.10.1796; Add. 34,904 f. 400

24

Nelson to William 2.6.1788; Nicolas I pp. 275–6

25

Nicolas I p. 288

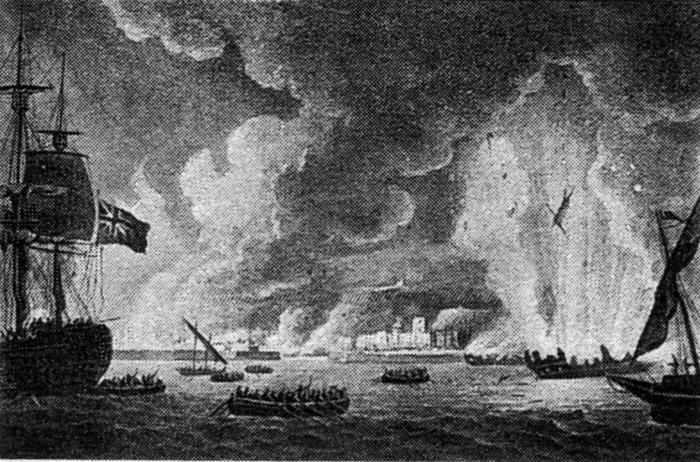

The burning of the French fleet at Toulon

CHAPTER III

In late 1792, as the European situation deteriorated and war with France came closer, the Navy began to mobilise. Once again, Nelson reminded the Board that he was anxious to serve. This time he did not rely on Hood, whom he had not spoken to since 1790. Within the month, however, he had seen Lord Chatham at the Admiralty, and had been promised a sixty-four as soon as it was ready, or a seventy-four if he was prepared to wait. Characteristically – and fortunately, as it would turn out – Nelson went for the more immediate prospect, although he was anxious to commission the ship at Chatham, rather than Portsmouth or Plymouth. He got his way, and his exuberance at the prospect was clear from his report of the interview to Fanny: duty called, and in his mind he was already off to sea. By late January he knew the name of his ship: the

Agamemnon,

then refitting at Chatham.

1

The symbolism of a ship named for the king of men might have been lost on the crew, who referred to her as ‘Eggs and bacon’, but it would be appropriate: over the next three years, the

Agamemnon

would make Nelson a prince among captains.

To man his new ship, Nelson called back many old

Albemarle

and

Boreas

officers and petty officers, recruited in Norfolk, and asked Locker, then commanding at the Nore, to find a clerk and extra men. There was a personal and parochial strain to his selections: his new-entry

midshipmen included Josiah Nisbet, a Suckling cousin, and William Hoste, son of another Norfolk parson. He would make them all captains, although only Hoste became a naval hero.

As he rushed back and forth between Burnham, London and Chatham, Nelson was still Hood’s man. Only slowly would he come to rely on his own judgement, and he never dreamt of refusing Hood’s orders as he had those of Hughes a decade earlier. While Hood held command Nelson deferred to him, although unlike most of his fellow captains he never ceased learning from the master. His period under Hood’s orders would be the penultimate stage of his education in leadership and command.

War was finally declared on n February 1793. Initially, the British government had not been unduly concerned by the outbreak of war between Austria and revolutionary France in 1792. The Prime Minister, Pitt, had convinced himself and his colleagues that the internal condition of France was a force for peace, leaving the Ministry profoundly unprepared later in the year when the French extended their war into the Austrian Netherlands (modern Belgium), an area of fundamental concern to Britain.

The French occupation of Antwerp undermined the basis of British security: a hostile fleet at Antwerp was ideally placed to attempt an invasion, far better than at any French base. Preventing the city from falling into the hands of a major rival had been the basic tenet of British policy since the Tudor period. The threat from the north-east would be a major issue throughout the next twenty-two years of war.

In 1793 Britain lacked the troops to take on France in the Low Countries, her old ally Holland was no longer a major power, and the military resources of the three eastern monarchies – Austria, Prussia and Russia – were largely occupied by the partition of Poland. In addition all three were close to bankruptcy. The minor powers and petty principalities of Europe were no better placed. The only assets that Britain could use to secure her strategic interests were her fleet, and her credit.

2

Pitt, committed as he was to fiscal stability, was convinced the French would be defeated by the collapse of their economy. To this end, Britain applied her major military effort to the French West Indian islands, the motor of their economy and source of key maritime resources, ships and seamen. The islands would also be useful assets for any peace negotiations, and end the threat to the immensely valuable West India shipping from locally based warships or privateers.

To address the European dimension of the French problem, Pitt needed to build coalitions based on mutual interest, money and sea power. Mediterranean strategy was driven by the need to secure a friendly base within the Straits. Gibraltar was unable to handle a large fleet, and without a major base, like Minorca, Naples or Malta, the fleet would be hard-pressed to protect British merchant ships, let alone exert any influence over France. As Hood’s fleet was assembling, British diplomacy was building a useful coalition. Piedmont-Sardinia signed a treaty in April, promising to keep fifty thousand troops in the field, in return for an annual subvention of

£

200,000 and the presence of a major fleet. The King of Sardinia was anxious to recover Nice and Savoy, which the French had seized in 1792. In July, Naples promised to provide six thousand troops and a naval squadron at no expense, although the British would have to transport the soldiers.

3

Further treaties with Spain and Portugal completed a Mediterranean system that encircled France, while providing bases and troops. Keeping the French fleet inside the Straits would greatly simplify the defence of oceanic trade, while providing distant cover for the West Indian campaign.

4

With a fleet in place, and allied armies to hand, France could be invaded on all fronts, her resources stretched along her frontier from Dunkirk to the Pyrenees.

As Commander in Chief in the Mediterranean, Hood was taking on the most complex task that fell to a British officer in wartime. While his primary task, like that of Howe off Brest, was to watch the French fleet and give battle if it came out, he was also responsible for theatre strategy, alliance-building and coalition warfare. Naval dominance, by battle or blockade, would enable Britain to use the Mediterranean for trade, diplomacy and strategy. He was to use any opportunity of ‘impressing upon the States bordering on the Mediterranean an Idea of the strength and Power of Great Britain’. This would require the fleet to be spread across the theatre.

By staying in port the French would force Hood to keep his battlefleet concentrated, while trying to protect trade from Gibraltar to the Dardanelles, cooperate with allies and clients and exert diplomatic leverage over the Barbary states. In conducting these multifarious tasks he would have to rely on his own judgement, forming his plans on the basis of local information supplied by British diplomatic representatives, and any intelligence that could be gleaned from passing ships, local newspapers, and chance occasions. Furthermore he would

have to operate without a major base, or dry-dock. It was a task that called for a range of skills above and beyond fleet command – it needed a self-sufficient, confident personality, with the political courage to take responsibility for major initiatives without being able to consult London. Only Hood and Nelson truly rose to the challenge of commanding the Mediterranean theatre.

*

In March the

Agamemnon

went down the Medway to Sheerness: Hood hinted that Nelson should prepare for a cruise and then join the fleet at Gibraltar. The combination of getting to sea and a letter from Hood put Nelson in fine spirits; he told Fanny that ‘I was never in better health’.

5

While the ship completed for sea Nelson’s personal possessions arrived on coasters from Wells. A short stretch down to the Nore in mid-April demonstrated a key feature of his command: ‘we appear to sail very fast’.

6

Desperate to join Hood, and fearful that his orders might change, he found every delay for bad weather a terrible trial. The vigour with which he drove two French frigates and a corvette into La Hougue, while cruising off the Normandy coast, spoke volumes about his anxiety to prove himself.

Nelson was anxious to get on with the war, and found another Channel cruise with Admiral Hotham’s division between Guernsey and Land’s End doubly annoying as neutral ships reported that the French Atlantic ports were full of captured British merchant ships.

7

Not content to do as he was told, Nelson needed to know the purpose of his orders, spending much mental effort trying to understand their rationale. This was an important lesson in command: as a result of his frustration, he himself would always take junior commanders into his confidence, ensuring they understood the broader mission so they could exercise their judgement rather than relying on orders.

The purpose of the cruise only became clear to Nelson later on: because the Channel fleet would take some time to mobilise, detachments preparing for the Mediterranean were being used to cover the western approaches before proceeding to their proper station. On 25 May Hood brought his division out to join Hotham, and took command of the fleet. The master quickly took his charges in hand, conducting tactical exercises as they waited off the Scilly Isles to cover the incoming Mediterranean convoy against a French fleet sortie. An outbound East India convoy also passed through this dangerous choke point. The next day the fleet headed for Gibraltar, and Nelson called

on Hood on board his flagship, HMS

Victory.

He was relieved to find Hood very civil, and told Fanny ‘I dare say we shall be good friends again.’ This personal warmth was vital, since without Hood’s approval Nelson would have cut a very sorry figure. Had he joined the Channel fleet, under the austere, uncommunicative Howe, his ardour for the service may have cooled.

As the fleet passed Cape Trafalgar heading for the Mediterranean, Hood detached ships to water at the Spanish naval base of Cadiz. For the first time in a century the British were welcome – inspecting the fleet, dining on the flagship and taking in the obligatory bullfight. A week in Spain left Nelson with mixed emotions: admiration for the large, well-built Spanish three-deckers, and confidence that as Spain lacked the sailors to man them they would be worth very little in battle. The failure of the Cartagena division to form a line of battle a week later only confirmed his estimate. Nor was he pleased by the savage spectacle of the bullring. For a man who would spend the critical hours of his life amidst the bloody shambles of the quarterdeck in close-quarters battle, he was remarkably sensitive about the maltreatment of animals.

Back at sea Nelson, already picked to lead one of the three divisions of the fleet, continued to ponder the purpose that led Hood to hasten the fleet out of Gibraltar Bay, confident the French ships would remain safely tucked up in Toulon. He started to keep a sea journal, a daily record of activity with reflections on his favourite subjects: men, measures and the weather. The journal was also used to produce letters home, appropriate segments being assembled with a more personal introduction for Fanny, Clarence, Locker, Edmund, William and uncle Suckling, among others.

8

These were usually replies to letters received; he did not have the leisure to pursue a polite correspondence.

Nelson’s active and enquiring mind was soon hard at work processing the intelligence gathered from neutrals, much of it unreliable ‘in my judgement’. Rumours that the French would fit their ships with furnaces to produce red-hot shot should, he believed, have been kept from the fleet. Ever the optimist, he hoped the blockade of Toulon and Marseilles would force the French fleet to come out.

9

Nor did he spare his colleagues, readily adopting Hood’s opinion that the first encounter between British and French warships had been mishandled.

10

Once off Toulon he could see the enemy: rumour had it that their flagship,

Commerce

de

Marseilles

, a vast ship of 136 guns, had

impenetrable sides. Nelson shared Hood’s hope that the blockade would force a battle, and picked up many more opinions from the flagship. The fast and handy

Agamemnon

and her dedicated young captain were constantly on the move. Consequently Hood’s offer of a seventy-four was refused – ‘I cannot give up my officers,’ he told Fanny. As the fleet was ready for battle and the war could not last long, it was the wrong time to leave a proven ship.

11

Cruising off Toulon, Nelson realised that Provence wanted a separate republic from Paris, but had no interest in restoring the monarchy, and that as Marseilles and Toulon were desperately short of food they might be handed over to the fleet. This might bring him home for the winter. Clearly in Hood’s confidence, Nelson told his father:

In the winter we are to reduce Ville France and Nice for the King of Sardinia, and drive the French from Corsica. It seems no use to send a great fleet here without troops to act with them.

12

Three days later, on 23 August, Hood signed a convention at Toulon that placed the fortress, fleet, town and arsenal in British hands in trust for a restored monarchy. Hood displayed remarkable political courage in seizing the opportunity, although his declaration was at variance with the views of the government, which was not committed to work for any specific regime in France. The example was not lost on Nelson, who would take more than one high-risk political decision in pursuit of strategic aims. Hood had taken twenty-two sail of the line, a fortress and a major arsenal from the enemy – by a stroke of the pen.

The government had considered a range of Mediterranean options, including attacking Toulon to destroy the French fleet, and securing Corsica as a fleet base. When Hood occupied Toulon in late August some in London saw it as a potentially war-winning stroke, opening the prospect of a counter-revolution. Yet the ministers had not anticipated this opening, and had no spare troops to exploit the opportunity, while Austria showed no interest in the project. After landing the troops on board the fleet as marines, Hood had to rely on Spain, Naples and Sardinia for most of his troops: Spain limited her involvement to a thousand men, yet still restricted Hood’s freedom of action, anxious that the French fleet should not pass to the British or be destroyed.

13

Although Hood worked well with the Spanish Admiral Gravina, he found the pessimistic British Generals O’Hara and Dundas a trial, and relied on his own officers for many key posts ashore.