Nemesis: The Last Days of the American Republic (24 page)

Read Nemesis: The Last Days of the American Republic Online

Authors: Chalmers Johnson

Although Italian political leaders have steadfastly maintained that they did not collaborate in any way with this kidnapping, it is obvious that police authorities knew a great deal about it. The nineteen-person CIA abduction team of commandos, drivers, and lookouts left an astonishing trail of evidence that suggests they were utterly indifferent to the possibility that they were being observed. The first operative arrived in Milan on December 7, 2002, and stayed at the Milan Westin Palace, according to court documents. The others started arriving in early January and by February 1, 2003, virtually all of them were there. They did not hide in safe houses or private homes but checked into four-star palaces like the Milan Hilton ($340 a night) and the Star Hotel ($325 a night). Seven of the Americans stayed at the Principe di Savoia—billed as “one of the world’s most luxuriously appointed hotels”—for between three days and three weeks at nightly rates of $450. Eating lavishly at gourmet restaurants, they ran up bills of at least $144,984, which they paid for with Diners Club cards that matched their fake passports. At each hotel, the staff photocopied their passports, which is how the police obtained their photos if not their real names.

117

After the delivery of Abu Omar to Aviano, four of the Americans checked into luxury hotels in Venice and others took vacations along the picturesque Mediterranean coast north of Tuscany, all still on the government tab.

Most embarrassingly, the U.S. embassy in Rome had supplied the CIA agents with a large number of Italian cell phones, on which they communicated with each other while planning the abduction, during the actual operation, and en route to Aviano. All their transmissions were recorded

by the Italian police. No one can explain this lapse in tradecraft. Unless its power is completely off and its antenna retracted, a European mobile phone remains in constant contact with the nearest cell-base station even when not in use. Since a phone is served by several base stations at any given time, investigators can easily triangulate its location. In cities like Milan, where the network of base stations is dense and overlapping, such tracking can be done with a margin of error of just a few yards.

118

Thus, the Italian police were able to follow everything that the nineteen agents did both prior to and on the actual day of the rendition.

After Abu Omar’s disappearance, the Italian police opened a missing person s investigation but did not pursue it very vigorously. That changed radically in April and May 2004, when Omar unexpectedly telephoned his wife from Cairo and explained that he had been kidnapped and taken to U.S. air bases in Italy and Germany, flown to Cairo, and tortured by the Egyptian police. The Italian authorities recorded these calls, having kept the wiretap on Omar’s apartment in place. He informed his wife that he had been let out of prison but remained under house arrest. There is speculation that, as a result of reports on these conversations in Italian newspapers, the Egyptian police rearrested him. In any case, as far as is known, he remains in Egyptian custody, not charged with any crime but allowed occasional visits by his mother.

There is still no explanation for the CIA’s sloppy work in Milan— except that some of its operatives seemed to have wanted a nice holiday at the taxpayers’ expense and believed they could operate with complete impunity in Silvio Berlusconi’s Italy. The Milan case goes into the record books as one more foolish and counterproductive felony committed by the CIA on the orders of the president. Ironically, the Milan CIA station chief had bought a house in Asti, near Turin, and planned to retire there. As the police bore down on him, he and his wife hurriedly fled their home, and a comfortable old age in Italy ceased to be an option for them.

Unfortunately, carrying out extraordinary renditions such as the ones in Sweden and Italy, torturing captives in secret prisons, shipping weapons to Islamic jihadists without checking their backgrounds or motives, and undermining democratically elected governments that are not fully on our political wavelength are the daily work of the Central Intelligence Agency. That was not always the case nor was it the intent of its founders or the expectations of its officials during its earliest years. As conceived in

the National Security Act of 1947, the CIAs main function was to compile and analyze raw intelligence to make it useful to the president. Its job was to help him see the big picture, put the latest crisis in historical and economic perspective, give early warning on the likely crises of the future, and evaluate whether political instability in one country or another was of any importance or interest to the United States. It was a civilian, nonpartisan organization, without vested interests such as those of the military-industrial complex, and staffed by seasoned, occasionally wise analysts with broad comparative knowledge of the world and our place in it. As the

New York Times’s

Tim Weiner notes, “Once upon a time in the Cold War, the CIA could produce strategic intelligence. It countered the Pentagon’s wildly overstated estimates of Soviet military power. It cautioned that the war in Vietnam could not be won by military force. It helped keep the Cold War cold.”

119

One of the CIA’s best-known historians, Thomas Powers, laments, “The resignation of Porter Goss after 18 months of trying to run the Central Intelligence Agency and the nomination [subsequently confirmed] of General Michael Hayden to take his place make unmistakable something that actually occurred a year ago: the CIA, as it existed for 50 years, is gone.”

120

I think it was actually gone long before. My own view is that President Bush’s manipulation of intelligence to deceive the country into going to war and then blaming his failure on the CIA’s “false intelligence” delivered only the final coup de grace to the CIA’s strategic-intelligence function. Henceforth, the CIA will no longer have even a vestigial role in trying to discern the forces influencing our foreign policies. That work will now be done, if it is done at all, by the new director of national intelligence. The downgraded CIA will attend to such things as assassinations, dirty tricks, renditions, and engineering foreign coups. In the intelligence field it will be restricted to informing our presidents and generals about current affairs—the “Wikipedia of Washington,” as John McLaughlin, deputy director and acting director of central intelligence from October 2000 to September 2004, calls it.

121

Thomas Powers is unquestionably correct when he writes, “Historically the CIA had a customer base of one—the president.” But equally historically, it was not understood at the beginning that the CIA would become the president’s private army as well as his private adviser. Over the years, presidents shaped what the CIA would become. They increasingly

believed that its strategic intelligence was a nuisance while its covert side greatly enhanced their freedom of action. Perhaps the idea of supplying leaders with strategic perspectives from an independent, nonpolitical source was always unrealistic. It seemed that the CIA only worked more or less as it was intended when the secretary of state and the director of central intelligence were brothers—as John Foster and Allen Dulles were under President Eisenhower. The reality was and is that presidents like having a private army and do not like to be contradicted by officials not fully under their control. Thus the clandestine service long ago began to surpass the intelligence side of the agency in terms of promotions, finances, and prestige. In May 2006, Bush merely put strategic analysis to sleep once and for all and turned over truth-telling to a brand-new bureaucracy of personal loyalists and the vested interests of the Pentagon.

This means that we are now blinder than usual in understanding what is going on in the world. But, equally important, our liberties are also seriously at risk. The CIAs strategic intelligence did not enhance the power of the president except insofar as it allowed him to do his job more effectively. It was, in fact, a modest restraint on a rogue president trying to assume the prerogatives of a king. The CIAs bag of dirty tricks, on the other hand, is a defining characteristic of the imperial presidency. It is a source of unchecked power that can gravely threaten the nation—as George W. Bush’s misuse of power in starting the war in Iraq demonstrated. The so-called reforms of the CIA in 2006 have probably further shortened the life of the American republic.

U.S. Military Bases in Other People’s Countries

The basing posture of the United States, particularly its overseas basing, is the skeleton of national security upon which flesh and muscle will be molded to enable us to protect our national interests and the interests of our allies, not just today, but for decades to come.

—COMMISSION ON REVIEW OF OVERSEAS MILITARY FACILITY STRUCTURE,

Report to the President and Congress,

May 9, 2005

9/11 has taught us that terrorism against American interests “over there” should be regarded just as we regard terrorism against America “over here.” In this same sense, the American homeland is the planet.

—The 9/11 Commission Report,

Authorized Edition (2004)

Wherever there’s evil, we want to go there and fight it.

—GENERAL CHARLES WALD

, deputy commander

of the U.S.’s European Command, June 2003

If you dream that everyone might be your enemy, one day they may become just that.

—NICK COHEN,

Observer,

April 7, 2002

Five times since 1988, the Pentagon has maddened numerous communities in the American body politic over an issue that vividly reveals the grip of militarism in our democracy—domestic base closings. When the high command publishes its lists of military installations that it no longer needs or wants, the announcement invariably sets off panic-stricken lamentations among politicians of both parties, local government leaders, television pundits, preachers, and the business and labor communities of

the places where military facilities are to be shut down. All of them plead “save our base.” In imperial America, garrison closings are the political equivalents of earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, or category five hurricanes.

1

The military, financial, and strategic logic of closing redundant military facilities is inarguable, particularly when some of them date back to the Civil War and others are devoted to weapons systems such as Trident-missile-armed nuclear submarines that are useless in the post-Cold War world. At least in theory, there is a way that this local dependence on “military Keynesianism”—the artificial stimulation of economic demand through military expenditures—could be mitigated. The United States might begin to cut back its global imperium of military bases and relocate them in the home country.

After all, foreign military bases are designed for offense, whereas a domestically based military establishment would be intended for defense.

2

The fact that the Department of Defense regularly goes through the elaborate procedures to close domestic bases but continues to expand its network of overseas ones reveals how little interested the military is in actually protecting the country and how devoted to what it calls “full spectrum dominance” over the planet.

Once upon a time, you could trace the spread of imperialism by counting up colonies. America’s version of the colony is the military base; and by following the changing politics of global basing, one can learn much about our ever more all-encompassing imperial “footprint” and the militarism that grows with it. It is not easy, however, to assess the size or exact value of our empire of bases. Official records available to the public on these subjects are misleading, although instructive. According to the Defense Department’s annual inventories from 2002 to 2005 of real property it owns around the world, the

Base Structure Report,

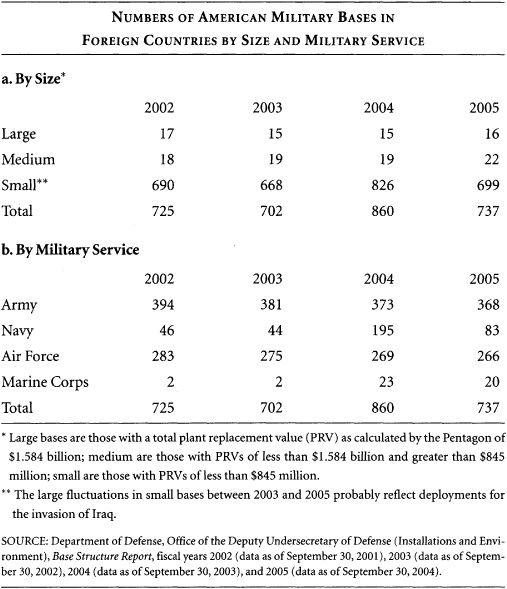

there has been an immense churning in the numbers of installations. The total of America’s military bases in other people’s countries in 2005, according to official sources, was 737. Reflecting massive deployments to Iraq and the pursuit of President Bush’s strategy of preemptive war, the trend line for numbers of overseas bases continues to go up (see table 1).

Interestingly enough, the thirty-eight large and medium-sized American facilities spread around the globe in 2005—mostly air and naval bases for our bombers and fleets—almost exactly equals Britain’s thirty-six naval bases and army garrisons at its imperial zenith in 1898. The Roman

Empire at its height in 117 AD required thirty-seven major bases to police its realm from Britannia to Egypt, from Hispania to Armenia.

3

Perhaps the optimum number of major citadels and fortresses for an imperialist aspiring to dominate the world is somewhere between thirty-five and forty.

TABLE 1 NUMBERS OF AMERICAN MILITARY BASES IN FOREIGN COUNTRIES BY SIZE AND MILITARY SERVICE