Niagara: A History of the Falls (18 page)

Read Niagara: A History of the Falls Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Blondin had been content to take up a collection after each exhibition of rope walking. Farini left nothing to chance. He engaged four excursion schooners to bring spectators from various points on Lake Ontario. He hired four bands to play aboard the steamers and then to entertain the paying customers in the enclosures he had erected for half a mile along the gorge. He had seats for forty thousand, who paid a minimum admission of twenty-five cents but more for reserved space.

No detail escaped his entrepreneurial grasp. He persuaded each of the two railways to pay him a bonus of one thousand dollars. He collected another $2,975 as his share of the steamship fares. Following his first performances he spent all day working with his ticket takers, checking receipts against numbers, and found he had collected $9,393.75. He realized an extra thousand dollars in a wager with a man who bet, foolishly as it turned out, that Blondin would draw a larger crowd. There were also small but unexpected profits from bystanders who on their own passed the hat for him as they had for Blondin. All in all, he collected about fifteen thousand dollars for his performance on August 15, 1860. “Not a bad sum for an hour’s work,” he remarked airily, but in fact it involved his most difficult feat.

Farini announced that he would descend to the

Maid of the Mist

, drink a glass of wine with one of the passengers, and then return by climbing up two hundred feet of rope. Off he went with a coil of rope over his shoulder – a slight but solid figure wearing buff tights, his long black hair and whiskers streaming in the wind. He fastened his balancing pole to the slack rope, using it as a seat, undid the coil on his back, let it down until it touched the water, and fastened one end to the rope on which he stood.

Below him, the little steamer, crowded with passengers, rocked and swayed in the rapids. Down he went, hand over hand, until, at the halfway point, the dangling rope began to twist. He was forced to coil one leg around it and close his eyes to ward off giddiness. The danger was lost on those below, who thought he was engaging in a new piece of daring.

He clung to the rope until it stopped twisting. Then he continued on down to the deck of the boat, drank the wine, acknowledged the cheers of the crowd, and started up again.

He had not climbed sixty feet before he was forced to call down to the men holding the rope to let go because the steamer was rocking so wildly in the current. The wind blowing down the gorge was causing the boat to swing back and forth like a pendulum. Farini figured that if he fell, it would be better to plunge into the water than onto the deck of the vessel.

He twisted a leg around the rope to rest his hands, then continued his climb. After another fifty feet he rested again, relieved that the swinging motion had diminished as the pendulum became shorter. He fought off drowsiness. His arms were stiff and tired, but he had another forty feet to go.

Now he had to stop and rest his arms every ten feet. When he was within twelve feet of his goal he almost gave up. His arms were numb, his hands too weak to bear his weight. Yet he forced himself to struggle on until he was within a yard of his objective.

One arm was now useless, the other almost so. He managed to worm his way up to a point where his nose just touched the horizontal rope. Using every last particle of strength left in one of his hands, he hung on while drawing a leg up as far as possible toward the rope and then, straightening his body, pulled his chest over. There he hung, totally exhausted and at his wits’ end to find a way to haul himself upright and continue his walk to the far shore. The only alternative seemed to be to drop into the water.

He continued to push with the leg that was still twisted around the dangling rope. At the same time he threw more of his weight onto his chest, relieving one arm. The arm seemed to be made of lead, but the circulation slowly came back. After a considerable struggle, he was able to get astride the rope. He rubbed his arms and unfastened his balancing pole but was too weak to raise it. He leaned back and threw up his legs, using them to raise the pole until his feet were on the rope. That brought the pole on his knees close to his chin. He bent forward and struggled to an upright position, using his left hand to move the swaying rope from one side to the other as his balance required.

He knew he must make the return crossing, as he had advertised, blindfold and with baskets on his feet. Off he went to the far shore, and with only ten minutes’ rest set out again. At one point he pretended to topple from the rope, a piece of showmanship that brought a chorus of screams. No one had screamed earlier when he was in real danger; all assumed that Farini the Great, struggling and dangling above the gorge, had done it many times before. It was, in fact, his first and only attempt of that kind and one that Blondin did not try to equal.

3

Farini the flirt

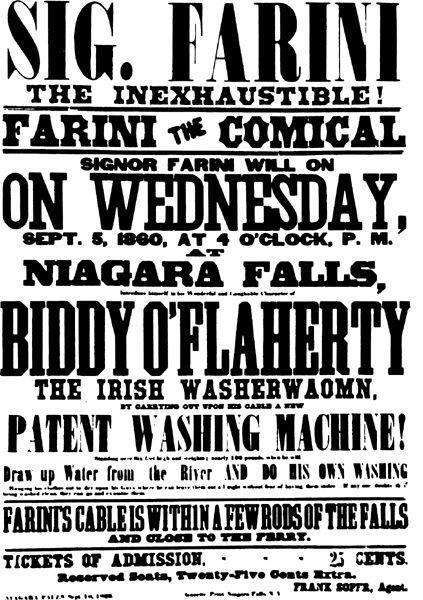

In the weeks that followed, Signor Farini matched Blondin feat for feat and sometimes topped him. He stood on his head, hung face downward by his toes, and carried a lanky volunteer, Rowland McMullen, across on his back. When Blondin walked the gorge in a sack, it did not cover his feet; Farini’s did. When a manacled Blondin crossed dressed as a Siberian slave, Farini countered by jigging across as an Irish washerwoman. Blondin had taken a stove out onto the tightrope and cooked an omelet. Farini carried a wash tub, lowered a pail into the river, and rinsed out a dozen pocket handkerchiefs. He had no difficulty obtaining these. They were pressed on him by admiring women who gasped at his daring, strove for introductions, ogled him at the receptions and balls held in his honour, and were delighted when the handsome twenty-two-year-old responded to their approaches, not always wisely but sometimes too well.

For Farini was not only a good businessman, he was also an unregenerate flirt. He had an eye for the ladies and they had an eye for him. In his memoirs he is not modest about his appeal, but he had reason to be cocky. With his tanned and bearded face, his long, jet-black hair, his muscular body, and, above all, his reputation as a daredevil, he had no difficulty in attracting women admirers.

After a grand ball given in his honour at Niagara in mid-August 1860, following his first performance, he was presented to “the wives and daughters of some of the most prominent men in America,” who showered him with cards and invitations. He was introduced that night to “a very beautiful Southern lady … with whom in consequence of her being too beautiful to resist,” he said, “I commenced a flirtation.” He found, however, that he was “encountering an adept at the art.” Apparently she matched him simper for simper. Nonetheless, “I did not do so badly for a beginner.” Just as he was in the middle of “a pretty series of compliments” another young woman seized him by the arm and bore him off. For the rest of the evening, he said, “my attentions were so evenly divided that to carry on the particular flirtation … was impossible, so I turned it into a general one and enjoyed myself considerably.”

“It is a wonder,” he wrote later, “my vanity did not overcome my reason.” When he retired for bed, he examined the various cards that had been given him that evening and found himself “in possession of invitations from ladies residing in every State in the Union.” The unfinished and unpublished memoirs of Farini are replete with such hyperbole. Yet there is a certain charm in the young man’s naïveté and insouciance, especially in those moments of Victorian melodrama that enliven his versions of various encounters.

He tells, for instance, of “a venturesome young lady whose recklessness was a source of much anxiety to me, feeling as I did morally responsible for her safety.” He had been escorting her through a passage behind the Luna Falls known as the Cave of the Winds and was standing with some others on the rough rocks near the water’s edge when he heard her scream. She had wandered off and, to his horror, tumbled into the rapids and disappeared beneath the foam.

Farini dove in head first and was instantly spun about by a whirlpool that dashed him against a rock. He thought the young woman had been sucked under, but then a movement near the surface caught his eye. He plunged back in and struck his head against her foot. His guide dragged them both out of danger, whereupon Farini performed a form of artificial respiration and with the help of others brought her around. “I picked up the fragile willful piece of loveliness and bore her through the passage, under the Falls, to the dressing room where I laid her on the sofa and administered some brandy and water.” Having observed her recovery, the gallant youth departed.

The following day he was invited to dinner by the lady’s parents, who insisted she apologize for having caused him so much trouble. Holding out “the prettiest little hands I ever saw,” she apologized for being “such a mad, silly thing” and told him she would be forever in his debt. She sat next to him at dinner that night and engaged him in a lively discussion of rope walking. After the meal, Farini excused himself, but only after “Miss V.,” as he discreetly called her, gave him her hand. “I felt a gentle pressure as she softly whispered, ‘I must see you again before you go.’ ”

The next morning as he took his customary walk along the shaded paths of Goat Island, he saw Miss V. wending her way through the birch trees in his direction. She seemed uneasy, greeting him with a faltering voice. He suggested a stroll toward the three half-submerged rocks in the rapids known as the Three Sisters. She slipped “her delicate little gloved hand” in his and the two gazed down into the dancing waters. Suddenly, she grasped his arm, as though in terror, and in true Victorian fashion fell insensible upon his breast.

He laid her down and splashed water on her face. She recovered and told him the purpose of her visit – he was “to refuse nothing papa may offer.”

“He was talking last night to mother,” she told him, “about presenting you with a testimonial, and I knowing your independent spirit was sure that if it assumed a pecuniary shape you would decline it with asperity and deem yourself insulted. To oblige me, I want you to accept what he offers.”

To which the chivalrous rope dancer, who had accepted – nay, encouraged – substantial donations following each of his exhibitions, declared that “the act of being of service to yourself is ample compensation and the look and smile you gave me on opening your eyes made me your debtor.” In fact, he insisted, the incident had contributed to his popularity. The press had gone mad over the rescue. Every paper had a different version, including one report that had her father insisting that they marry, and that he, Farini the Great, had agreed. As for him, a smile from her was his reward.

“Please do not think me unladylike,” the young lady responded, “if I say I wished … wished … no, I cannot say it, it’s too indelicate.”

“Say whatever you like, Miss V., I am no lover of the conventional.”

“Can’t you guess?” she whispered. “Can’t you form an idea of my meaning?”

He feigned ignorance, urged her to say what was on her mind, offered to turn away if it would save her embarrassment.

“No, no!” she cried passionately. “Do not turn away and I will tell you what my wish was, it was that the account given in the paper was true.”

With that avowal, tears sprang to her eyes, leaving Farini nonplussed. He told her that she had paid him the greatest compliment any woman could pay a man, that he had no language adequate to express his admiration for her, but he pointed out gently that she had a romantic and impulsive nature and there were others “whose opinions you must respect and whose happiness you must consult.” She would, he declared, think kindly of him for what he had said.

No Victorian novelist could have improved on Farini’s version of his final rejection: “At some future date I may meet you on equal terms, both in wealth and love, and then should your mind be unchanged, I will not hesitate to ask the consent of your parents to my being the caretaker for life of a treasure infinitely more valuable than all their money. Such a course as this, I am sure, is preferable to my accepting you in payment of a debt which never existed and showing myself to be more rapacious than Shylock who demanded a pound of Christian flesh for a real debt, while I should be carrying off many pounds for an imaginary one.”

At that she called him cruel and cold and, pressing his hand, whispered goodbye. That night, one of the waiters at the International Hotel on the American side brought him an envelope containing five one-hundred-dollar bills and a note of thanks. The family had already left Niagara, but Farini insisted the hotel mail the money to the father. Shortly afterward, the proprietor’s wife, Mrs. John Fulton, handed him a note that Miss V. had left for him. It said: “Something tells me that we may never meet again.… Amidst all the excitement and danger of your calling, do not forget that the life you saved is ever yours.… –V.”

There were other assignations. After one of his performances in August, Farini found himself involved in an equally dangerous encounter with “a very handsome lady” who struck up a conversation with him following the performance and, seeing his face beaded with sweat, handed him a silk handkerchief to wipe his brow. As he counted the day’s proceeds, his mind went back to the incident. Had she forgotten the handkerchief? Or had she left it on purpose? He must find out. He saw that it was embroidered with the monogram L.M., but there was nobody with those initials to be found on the International’s register. He tried the Cataract House, and there the desk clerk told him that a Miss Louisa Montague had just returned to Buffalo with a party of friends.