Niagara: A History of the Falls (3 page)

Read Niagara: A History of the Falls Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

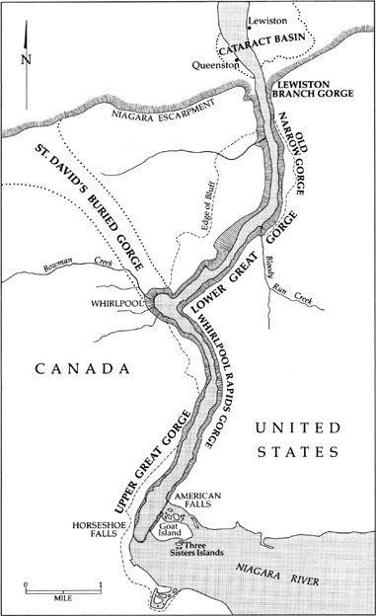

Through the process of erosion, the great cataract has created five distinct gorges through which the Niagara River has flowed between Queenston and the present site. That wearing away cannot be halted. All that human beings can do is to try to slow it down.

The shape of each gorge derives from the different volumes of water that once flowed out of old Lake Erie at varying speeds during the retreat of the last ice sheet. These were not constant. Sometimes the ice acted as a dam, changing the direction of flow from the Great Lakes Basin to the sea. There were times when most of the water spilled northeast toward the St. Lawrence. There were other times when it flowed southeast to the valley of the Hudson. When Erie was thus isolated, only a small amount of water poured over the Falls, digging out a narrow gorge, but when the entire flow from the Great Lakes filled the Niagara, a broader passage was created.

The five gorges of the Niagara River

The first gorge to be chiselled out by the cataract, known today as the Lewiston Branch Gorge, was a canyon that ran upstream for two thousand feet before it changed character. When the Falls reached that point, the volume of water lessened. The eastern side of Lake Tonawanda had dried up when Lake Erie could no longer supply as much water as formerly. The main flow from the vast inland ocean known as Lake Algonquin (it covered three of the present Great Lakes) followed a different route through the region of the Trent River valley to Lake Iroquois, bypassing ancestral Lake Erie and reaching the sea by way of the Hudson. Erie became temporarily independent of its sister lakes. With so little water available, the Falls carved out a much narrower gorge (called the Old Narrow Gorge). The surrounding land, released slowly from the crushing pressure of the retreating ice, rose and tilted imperceptibly, and the drainage took new directions. Eventually, the Algonquin waters that had once flowed east and north flowed again into Erie. This increased volume produced the broad channel known today as the Lower Great Gorge. And here the cataract, fighting its way slowly upstream, encountered the subterranean remains of a much older watercourse.

A few thousand years before the last advance of ice smothered the Escarpment, an earlier Niagara River flowed northwest, gnawing out a gorge all the way back from the site of the town of St. Davids to the head of the present Whirlpool Rapids Gorge. Re-advancing ice had filled this channel with the usual debris of broken rocks and soil so that it was hidden beneath a mantle of earth and vegetation until the Falls, working upstream from the edge of the Escarpment above Queenston, collided with it.

The softer debris in the buried gorge offered less resistance than did the hard dolostones of the Lower Great Gorge. The Niagara River could then quickly tumble over the wall of the glacial rubble and scour out the soft clays and sands, creating the Whirlpool Basin and re-excavating the Whirlpool Rapids Gorge. The fascinating Whirlpool Basin marks the intersection of the older and the younger channels of the Niagara River. The evidence is in the northeast wall for all to see.

Goat Island

The retreat of the ice led to the draining of Lake Iroquois and the lowering of the water level of the subsequent Lake Ontario. A new route east through the valleys of the Mattawa and Ottawa rivers acted as drainage for Lake Algonquin, lowering its level and drying up its outlet through Lake Erie.

The land around the Great Lakes, continuing its recovery from the crushing pressure of the ice, slowly tilted south, changing the drainage pattern so that once again the waters of Algonquin flowed out into Lake Erie and surged into the Niagara. As the volume increased, the erosion of the canyon accelerated and widened. The cataract, moving at a rate that may have reached six feet a year, continued to work its way upstream. Thus was begun, at the time of the building of the pyramids, the broader chasm known as the Upper Great Gorge that leads to the present site of Niagara Falls.

Here, some five hundred years ago, the river encountered an obstacle that caused it to split into two channels. This was Goat Island, created of silts and clays that had originally lain on the bottom of the vanished Lake Tonawanda. On the eastern side of the island, the American Falls took shape, on the western side, where the river makes an abrupt, ninety-degree turn, the Horseshoe. The island’s sheer northwestern face, rising 170 feet from the basin below the furious waters, divides the two cascades.

The waters immediately surrounding Goat Island are relatively shallow and studded with small islets and large isolated rocks, many of them the scenes of dramatic rescues and rescue attempts. Goat Island is so close to the American shore that only a small amount of Niagara’s flow plunges over the edge on that side. As a result, the American Falls are not as effective at erosion as the Horseshoe. The channel here is broken by well-known landmarks such as Bath Island, long used as an anchor for the bridge to Goat. Luna Island divides the American cataract, forming a third waterfall, slender and shimmering, variously known as Luna Falls, Iris Falls, or Bridal Veil Falls.

On the Canadian side of Goat Island, several historic pinpoints of rock stand out from the shore, washed by the spray of the racing river. The Three Sisters islands at the southwest end of the island are the best known, but at one time the Terrapin Rocks, so called because they resembled gigantic tortoises, were equally famous. The water here was so shallow that a slender bridge was constructed out to the rocks and a stone tower built on the very lip of the Horseshoe Falls. The tower did not last out the nineteenth century; the danger from erosion caused the owners to destroy it. But Terrapin Point remains. In 1955 the area was permanently drained of water and back-filled to create an artificial viewing space, perhaps the best of all the vantage points. Here, on the western rim of Goat Island, thousands of visitors look down over the cataract at the very point where the waters hurl themselves over the precipice, 170 feet to the vortex below.

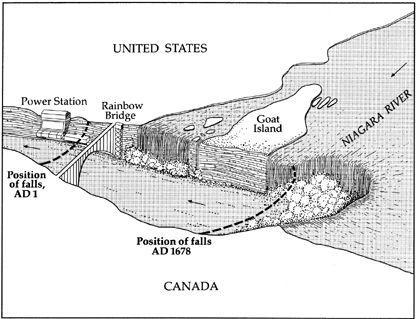

Farther out from Goat Island toward the Canadian shore, the river deepens. Here the current is so strong that the shape of the cataract is constantly changing. Since the first white man, Father Hennepin, reported on the Falls more than three centuries ago, the waterfall has moved about a third of a mile upriver and changed from a gentle curve to a horseshoe bend to today’s gigantic inverted V with it point upstream, where the tumbling waters, tearing away at the dolostone, have created a deep notch. It will change again, for it appears to have oscillated between horseshoe-shape and notch-shape over the centuries depending on the rate of recession.

The shape of the American Falls is also changing. Once this fall was likened to a gigantic weir, its crest a straight line between Goat Island and the opposite shore. But once again the implacable river, tearing out the softer shale, has caused the hard dolostone cap to crumble, leaving a familiar V-shaped notch at the western side to destroy the symmetry.

So powerful is the thrust of the water plunging off the Horseshoe that it has gouged out a hollow beneath the level of the riverbed some two hundred feet deep. On the American side, the pressure of the water is not strong enough to move the piles of talus – broken rock – that are heaped up to more than half the cataract’s height.

The Falls can never be totally controlled, even though modern engineers have come close. The cataract can now be turned off at the pull of a lever. And even at the peak tourist periods in the daylight hours of summer, Niagara Falls is not quite what it once was. Today less than half the river’s flow (and even less than that in the dark of winter) pours over the precipice. The remainder is carefully channelled into tunnels and canals to feed the great power stations that face each other across the gorge just south of Queenston.

Nobody can see the cataract today in all its splendour as the Victorian visitors in their top hats and bonnets saw it. But then, the Victorians in their turn could not see Niagara Falls as the native peoples and the early explorers saw it – a terrifying display of thundering water, hidden at the end of a dizzy gorge, framed in a luxuriant jungle of foliage, half-concealed by the pillaring mists, unprofaned by the hand of humankind.

Each era has had its own vision of Niagara Falls. Some have seen it as a manifestation of the Deity’s omnipotence, others as a Gothic horror lurking among nameless dangers. For every person entranced by its beauty, there has been another seduced by its power. Some have seen it as a backdrop for a non-stop carnival; others have wanted to preserve it exactly as the first explorers found it; and more than a few have wished to destroy it in the interests of science and commerce.

The noble cataract reflects the concerns, the fancies, and the failings of the times. If we gaze deeply enough into its shimmering image, we can perhaps discern our own.

2

A prodigious cadence

Within half a century of the discovery of the New World, the European explorers began to hear whispers of an immense waterfall hidden away in the wild heart of the unknown continent. Jacques Cartier may have had a hint of it from the Indians as early as 1535. Samuel de Champlain was told of it in 1603 and marked it on the map simply as “waterfall.” That exotic forest creature Etienne Brûlé, the first white man to reach the Great Lakes, almost certainly saw the Falls sometime before the Hurons killed him in 1633. But he left no personal record of his journeys and adventures.

In the seventeenth century, the Falls was a place of mystery and even magic. A sort of medical missionary, François Gendron, gave a hearsay account, in 1660, of how spray from the Falls was petrified into a form of rock or salt, “of admirable virtue for the curing of sores, fistules, and malign ulcers.” Two centuries later, confidence men would still be hawking “congealed spray” from the cataract.

The first eyewitness description of Niagara Falls did not appear until 1683, when Father Louis Hennepin, a Recollet priest who had accompanied René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, on his journey in search of the Mississippi, published his

Description de la Louisiane

, an instant best-seller that went into several editions. Fifteen years later he expanded and revised, not always accurately, his first brief report on the cataract.

A butcher’s son from the Belgian town of Ath, Hennepin by his own account “felt a strong inclination to fly from the world” and so joined the austere missionary order of Recollets, mendicant friars who owned nothing but the grey cloak and cowl that was their habit. Hennepin was a mass of contradictions. He wanted to retire from the world, and yet he longed to travel to strange lands and yearned for high adventure in exotic places. Sent on a mission to the port of Calais, he fell “passionately in love with hearing the relations that Masters of Ships gave of their Voyages.” Often he would hide behind the doors of taverns, eavesdropping as sailors talked of “their Encounters by Sea, the Perils they had gone through, and all the Accidents which befell them in their long Voyages.”

His dreams were realized in 1675 when, at the age of about thirty-five, and no doubt at his own urging, he was selected as one of five of his order to take passage for New France. The ship’s company included two great figures of the French regime, François de Laval, the first Bishop of Quebec, and La Salle, the future explorer.

Hennepin and La Salle, whose subsequent westward expedition he was to join, struck sparks off one another from the outset. A single incident suggests a great deal about Hennepin – his prudery, his belligerence, his sensitivity. On board ship was a group of young women, a small contingent belonging to that grand company of more than one thousand

filles du roi

, the “King’s Daughters,” sent out to New France as prospective wives for settlers and soldiers. The zealous young cleric found their behaviour immodest and took it upon himself to lecture them for “making a lot of noise with their dancing” on the transparent pretext that they were keeping the sailors from their rest. He had no sooner rebuked the women than La Salle rebuked

him

. A cantankerous argument followed, which the touchy Hennepin would never forget. La Salle, he was to claim, turned pale with rage and from that point on persecuted him.