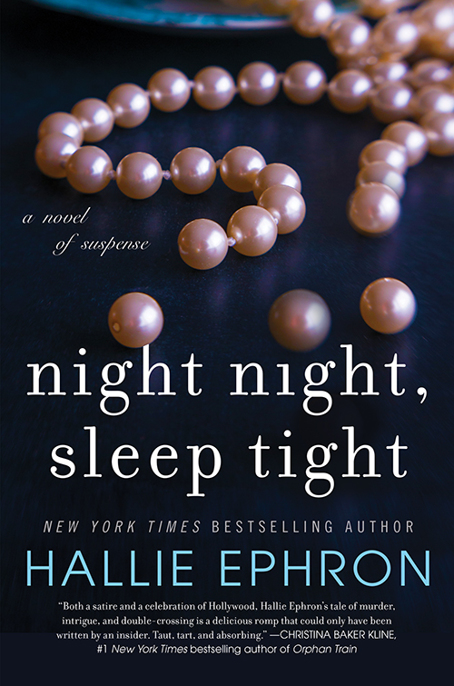

Night Night, Sleep Tight

Read Night Night, Sleep Tight Online

Authors: Hallie Ephron

O

ne of the pleasures of writing this book was taking a trip back in time, remembering what it was like to grow up in Beverly Hills. A special thank-you to the folks in the “Beverly Hills in the 50s & 60s” Facebook group for sharing their remembrances, as well as to friends Jodyne Roseman and Ellen Kozak. For a sanity check on Hollywood and the movie business, thanks to my sister Delia Ephron.

Thanks to Lee Lofland for help on police procedure; to Deb Duncan on insurance fraud; to Paula Shelby on the workings of a Harley dealership; to Susannah Charleson on arson investigation; to Clarissa Johnston, MD, on trauma; and to Michelle Clark on death investigation.

For help working my way out of plot holes, thanks to generous fellow writers Paula Munier, Roberta Isleib, Hank Phillippi Ryan, and Jan Brogan.

I am deeply indebted to my agent, Gail Hochman, and my editor, Katherine Nintzel, for their clearheaded critiques and encouragement. Seriously. Thank you. Thanks to assistant editor Margaux Weisman for help shepherding this manuscript through to publication.

Thanks to Joanne Minutillo, Danielle Bartlett, Tavia Kowalchuk, and the other amazing folks in publicity at HarperCollins for their talent and enthusiasm launching this book.

Thanks to Jim and Anne Hutchinson, whose generous donation to Raising a Reader purchased a character name for their son Jack.

And finally, thanks to my husband, Jerry. Without his patience and forsaken weekend outings, this book never could have been written. He, more than anyone, was glad to see it finished.

Contents

A

rthur Unger slides open the glass door and steps out onto his flagstone patio. He’s had a few drinks but he doesn’t feel them. It’s late at night, and though the sky is clear and there is no moon, there are no stars, either. There never are. Between ambient light and air pollution, he’d have to drive to Mount Baldy to see Orion’s Belt.

The sky is . . . He gazes up at it.

Opaque? Inky? Like warm tar?

His ex-wife would have nailed it. She was great at narrative description and dialogue. And of course, she could type. He was the plotmeister. Arthur takes a final drag on his cigarette, the tip glowing in the dark, and stubs it out in one of the dirt-filled, terra-cotta planters in which Gloria once cultivated gladiolus. Or was it gardenias? Something with a

G

.

He picks up one of three cut-glass tumblers sitting on the table on the patio, left over from tonight’s unpleasantness. Why does he have to rehash what was agreed on and settled years ago? He did what he promised.

D

E

B

T

P

A

I

D

I

N

F

U

L

L

should be stamped across his forehead, and he has the paperwork to prove it.

He raises the glass in a toast.

To the end of old debts and life without gardenias.

He knocks back lukewarm, scotch-flavored ice melt, then reaches into the house and flips a light switch. The water in the pool—it’s just twenty-five meters long, not the size to which he feels entitled, not what he expected to have earned by this point in his life—glows radiant turquoise against a row of coral tiles above the waterline.

Arthur imagines his yard is a movie set. A camera dolly backs up in front of him as he strides across the lawn in terrycloth slippers, an open Hawaiian shirt, and bathing trunks. A pair of amber-tinted swim goggles hangs loose around his neck. He reaches to unlatch the gate in the utilitarian chain-link fence surrounding the pool, but it’s already open. Careless. He once had to scoop a neighbor’s Chihuahua from that pool, and he has no desire to fish another dead animal from the water.

He slips through the gate and latches it behind him. Tosses a towel over a chaise longue made of aluminum tubing and white vinyl strapping. Takes off his shirt and drapes it there, too.

Arthur is in his late fifties, conscious of once taut muscles in his chest that sag if he exhales and relaxes at the same time. Even alone in his own backyard he tries not to let down his guard. Tonight he looks tired, the dark pouches under his eyes echoing the flab in his gut. He needs his thirty laps to drain away anxiety, get his blood flowing, and make him feel sufficiently worn out to fall asleep without a Valium and another scotch.

The pool has been skimmed, at least. That’s supposed to be his son’s job, but Henry rarely notices that it needs skimming. Rarely notices much at all, in fact. Henry seemed stunned when Arthur told him the house has to go on the market, though this would be patently obvious to anyone living here and even minimally aware of anyone’s needs but his own.

Time to grow up, baby boy.

That’s a line from a musical comedy Arthur and his wife wrote.

Show Off

was supposed to star Judy Holliday and Dean Martin, but she dropped out to have throat surgery. And then, of course, there was the breast cancer. Tragic for her. Tragic for audiences to lose such a brilliant comedic talent.

Arthur first met Judy way back when . . . He closes his eyes and tries to remember. He must have been working as assistant stage manager at the long-ago razed Center Theatre in Manhattan, a gorgeous art deco ark at Forty-Ninth and Sixth. Late nights, after the show, he’d take the subway down to the Village where Judy performed a cabaret act with Betty Comden and Adolph Green, accompanied at the piano by fellow unknown Leonard Bernstein. They were all so young. So talented.

Show Off

could have been big. Should have been big. Would have kicked his and Gloria’s career back into high gear. Plus he’d have scored a producing credit and points on the back end. Even with the studio’s creative bookkeeping, eventually it might have earned him a decent-sized pool and enough in the bank that he could have offered to help out his kids when they needed it.

But he’s not out of the game yet. His book could catapult him back onto the A-list. It’s the quintessential Horatio Alger story. He’ll write the screenplay. Direct the film version. Cast a great actor in the lead. Someone capable of nuance. Subtlety. A little comedic flair. Maybe he’ll give himself a walk-on cameo.

Arthur runs his fingers back and forth through his hair, still dark and thick and curly, about the only good thing that both he and Henry inherited from Arthur’s father. Then he stretches, arms wide, fingers splayed. Inhales deeply. Coughs. He tries to imagine his girls,

ingenues

as they were once called, perched around the edge of the pool. He sees the camera panning from one to the next, sliding appreciatively across cleavage and shapely leg, then over to him as he smiles benevolently back at them.

Give a little, get a little.

That’s always been his motto. Only lately he’s been getting just that. A little. And sometimes not even that.

He adjusts his swim goggles over his eyes. His girls, if they were really there, would be a golden blur now. The camera dolly would have faded into murky darkness. He imagines it tracking him as he steps slowly, deliberately to the deep end of the pool. The wall of his garage, lit by a wavery glow, makes an eerie backdrop as his shadow creeps up it, nearly reaching the windows of his second-floor office. In a film, it would feel like foreshadowing. Very dramatic. Perhaps a bit melodramatic—at least that’s what Gloria would have said, and she’d have been right.

Arthur faces the pool. Centers himself. Three long strides and he feels the concrete apron around the pool under his bare foot. A leap and he’s airborne, outstretched and arcing in a racing dive. He lands more heavily than he’d like and the water is a lot colder than he expects, but the initial shock quickly recedes.

He swims, stroke after stroke after stroke, a turn of his head to take a breath. He reaches the far end, barely pausing before pushing off and surging in the opposite direction. Back and forth. He’s nearing the zone, the place where his mind lets go and muscle memory takes over. He starts to review his work in progress the way he used to work through a movie script, running the maze of major and intermediate plot points; unpacking the emotions, goals, and obstacles that drive them; probing at knots and dead ends until he’d worked them through.

But what rises to the surface, like the taste of a bad oyster, is last week’s phone call and tonight’s meeting. Arthur feels his shoulders tensing up, his breathing begin to labor. If he wanted to be dictated to, told what he could and couldn’t write, he’d be working on a screenplay.

He’s not looking forward to tomorrow’s meeting with the Realtor. She advised him to list the house at 899K. Apparently nine hundred is a barrier for buyers, and even though the market is hot, his house is not. How did she put it in the ad copy?

A classic open-plan home with lots of possibilities.

In other words, a dump. But hey, it’s Beverly Hills, even if it is in the flats south of Sunset, and Arthur is determined to list his house for an even mil. Let them underbid and think they’re getting a bargain. One thing he’s learned: you don’t ask, you don’t get.

His daughter, Deirdre, agreed to drive up from San Diego tomorrow and spend a few days helping him get the place ready to go on the market. He called to remind her before coming out for his swim, but she didn’t pick up the phone. Probably sleeping—Arthur loses track of the time. It’s no big deal because Deirdre has never needed reminding. Even when she was little, she got out of bed and dressed for school without having to be coaxed. She did her homework. As grueling as the physical therapy was, she just did it, never complaining, even when it was clear that it wasn’t going to make any difference.

Once he’d have taken Deirdre for granted. But having someone he can depend on is something he cherishes now. Especially since he hasn’t exactly earned her undying loyalty. She blames him for the car accident that crippled her, and how could she not? It’s the kind of thing that apologies can’t fix, though Lord knows he’s offered them up.

Apologies. Excuses. Anything but the truth. It really wasn’t his fault, but he can’t tell her that, because if it wasn’t his fault, then whose was it? He can’t go there. Not yet, anyway. Maybe never. Besides, it’s the last thing Deirdre wants to hear and it won’t bring her the peace he wishes he had to give her.

He strokes across the pool. Turns.

He means to thank Deirdre properly this time. Maybe send flowers to that art gallery of hers. Her constancy is such a support these days. Henry seems incapable of fulfilling even the smallest commitment unless it involves one of his dogs or his muscle bikes. Gloria left years ago. Oh sure, they talk on the phone, though only occasionally, and not since Gloria began a monastic retreat. Tibetan Buddhist, shaved head, vegan diet, the works.

He tries to let go, to push away unfinished business as he pushes off from the end of the pool. As he strokes, he tells himself,

There’s always tomorrow

. A wrong-answer buzzer goes off in his head. As Gloria often chided him:

Focus on the now.

In this moment, as he swims in a steady rhythm, he is the star of his own movie, his life story brought to the silver screen, his backyard the set. The director, hidden in darkness behind the camera, has long ago called for

Quiet! Roll camera! Action!

Fade in.

All attention is focused on Arthur as he turns again at the far end of the pool.

A beat.

He plunges back in the opposite direction, stroking powerfully toward the spotlight where . . . Who? Billy Wilder and Elizabeth Taylor, he decides, are waiting for him to surface and accept a golden statuette with his name engraved on the base. Recognition of his lifetime achievement, something even his kids can feel proud of.

Ready for his close-up, Arthur reaches the opposite end of the pool, raises his head, and hangs there for what he thinks will be just a moment, basking in the illusion that he’s the star of his own show. Realizing too late that the spotlight he sees through the goggles—a yellow, water-streaked glow—is real and getting bigger, until it’s bright and blinding and right in his face.

He blinks and looks away, and in that split second the light goes out. And we hear the sound that Arthur can’t—the thud of heavy metal connecting with Arthur’s head, his prefrontal cortex to be precise, the part of his brain responsible for a lifetime’s worth of lousy decisions and selfish moves.

It’s a wrap.