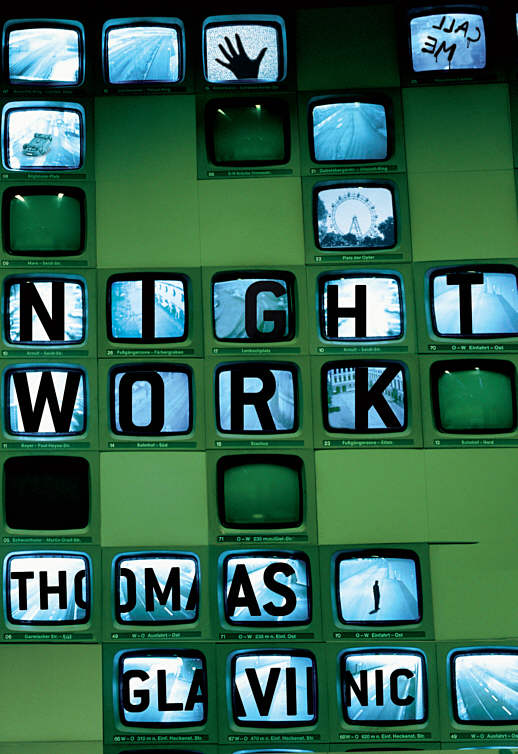

Night Work

Authors: Thomas Glavinic

THOMAS GLAVINIC

Translated from the German by

John Brownjohn

There’s no happiness in living,

in bearing one’s suffering self through the world.

But being, being is happiness. Being: transforming

oneself into a fountain into which

the universe falls like warm rain.

Milan Kundera,

Immortality

Title Page

Epigraph

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Also by Thomas Glavinic, Available in English

Copyright

‘Good morning!’ he called as he entered the kitchen-cum-living-room.

He carried the breakfast things to the table and turned on the TV. He sent Marie a text:

Sleep well? Dreamt about

you, then found I was awake. ILU

.

Nothing on the screen but snow. He zapped from ORF to ARD: no picture. He tried ZDF, RTL, 3sat, RAI: snow. The Viennese local channel: snow. CNN: more snow. French-language channel, Turkish-language channel: no reception.

No

Kurier

on the doormat, just an old advertising leaflet he’d been too lazy to remove. Shaking his head, he pulled one of last week’s papers from the pile in the hall and went back to his coffee. Made a mental note to cancel his order. They’d already failed to deliver it once last month.

He surveyed the room. The floor was strewn with shirts, trousers and socks, and last night’s dirty plates stood beside the sink. The waste bin stank. Jonas pulled a face. He yearned for a few days’ sea air. He ought to have gone with Marie, although he disliked visiting relations.

When he went to cut himself another slice of bread the knife slipped and bit deep into his finger.

‘Damn! Ah! What the …?’

Gritting his teeth, Jonas held his hand under the cold tap until the blood stopped flowing. He examined the wound. He’d cut himself to the bone, but he didn’t appear to have damaged a tendon. It didn’t hurt, either. There was a neat, gaping slit in his finger, and he could see the bone.

He felt queasy, took some deep breaths.

No one, himself included, had ever seen what he could see. He’d lived with this finger for thirty-five years without ever knowing what it looked like inside. He had no idea what his heart looked like, or his spleen. Not that he’d have been particularly interested in their appearance, far from it. But this bare bone was unquestionably a part of him. A part he’d never seen until now.

By the time he had bandaged up his finger and wiped the table, he’d lost his appetite. He sat down at the computer to check his emails and skim the world news. His browser homepage was set to Yahoo. A server error message appeared instead.

‘Damn and blast!’

He still had time, so he dialled the help line. The automated voice listing alternatives didn’t answer. He let it ring for a long time.

*

At the bus stop he took the weekend supplement from his briefcase. He hadn’t had time to read it before. The morning sun was dazzling. He felt in his jacket pockets, then remembered that his sunglasses were lying on the chest in the hall. He checked to see if Marie had texted him back, opened the paper again and turned to the Style section.

He found it hard to concentrate on the article. Something was puzzling him.

After a while he realised he was reading the same sentence over and over again without taking it in. He clamped the newspaper under his arm and took a few steps along the pavement. When he looked up he saw there was no one else in sight. Not a soul or a car to be seen.

A practical joke was his first thought. Then: it must be a public holiday.

Yes, that would account for it, a public holiday. Telephone engineers took longer to repair a faulty line on public holidays. Buses were more infrequent too. And there were fewer people in the street.

Except that 4 July wasn’t a public holiday. Not in Austria, at least.

He walked to the supermarket on the corner. Shut. He rested his forehead against the glass and shaded his eyes with his hands. No one there. So it had to be a public holiday. Or a strike, and he’d missed the announcement.

On his way back to the bus stop he looked round to see if the 39A was turning the corner. It wasn’t.

He called Marie’s mobile. No reply, not even her recorded message.

He dialled his father’s number. He didn’t answer either.

He tried the office. No one picked up the phone.

Werner and Anne were both unobtainable.

Bewildered, he replaced the mobile in his breast pocket. At that moment it occurred to him how utterly quiet everything was.

He went back to the flat and turned on the TV again. Snow. He turned on the computer. Server error. He turned on the radio. White noise.

He sat down on the sofa, trying to collect his thoughts. His palms were moist.

He went to the corkboard in the kitchen and consulted a grubby slip of paper Marie had pinned up years ago. It bore the phone number of the sister she was visiting in

the north of England. He dialled it. The ringing tone was different from the Austrian one, lower and consisting of two short purring sounds. After listening to it for the tenth time, he hung up.

*

When he went outside again he peered in both directions. He didn’t pause on his way to the car, just glanced over his shoulder a couple of times. Then he stood and listened.

Nothing to be heard. No hurrying footsteps, no throat-clearing, not a breath. Nothing.

It was stuffy inside the Toyota. The steering wheel was so hot, he could only touch it with the balls of his thumbs and his bandaged forefinger. He wound the window down.

Nothing to be heard outside.

He turned on the radio. White noise on all stations.

He drove across the deserted Heiligenstädter Brücke, where the traffic was usually nose-to-tail, and along the embankment towards the city centre. He kept an eye open for signs of life, or at least for some indication of what might have happened here, but all he saw were abandoned cars neatly parked as if their owners had merely nipped inside for a moment.

He pinched his thighs, scratched his cheeks.

‘Hey! Hello!’

On Franz-Josefs-Kai, driving at over seventy k.p.h. because he felt safer that way, he was flashed by a speed camera. He turned off onto the ring road that separates the centre of Vienna from the rest of the city and upped his speed still more. At Schwarzenbergplatz he debated whether to stop and look in at the office. He sped past the Opera, the Burggarten and the Hofburg doing ninety. At the last moment he braked and drove through the gate into Heldenplatz.

Not a soul in sight.

At a red light he screeched to a halt and killed the engine. Nothing to be heard but metallic pings from under the bonnet. He ran his fingers through his hair and mopped his brow, clasped his hands together and cracked his knuckles.

Something suddenly struck him: there wasn’t even a bird to be seen.

*

He skirted the 1st District at high speed until he found himself back in Schwarzenbergplatz. Turning right, he pulled up just beyond the next intersection. Schmidt & Co.’ s offices were on the second floor.

He looked in all directions. Stood still and listened. Walked the few metres back to the intersection and peered down the adjoining streets. Parked cars, nothing else.

Shading his eyes, he squinted up at the office windows and called his boss’s name. Then he pushed the heavy door open. Cool, stale air wafted to meet him. He blinked, still dazzled by the brightness outside. The lobby was as gloomy, grimy and deserted as ever.

Schmidt & Co. occupied the whole of the second floor, six rooms in all. Jonas toured them one by one. He noticed nothing out of the ordinary. Computer screens on desks with stacks of paper beside them. Walls hung with garish amateur daubs by Anzinger’s aunt. Martina’s pot plant in its usual place on the window sill. Rubber balls, building bricks and plastic locomotives lying forlornly in the crèche corner installed by Frau Pedersen. His progress was obstructed at every turn by bulky parcels containing the latest consignment of catalogues. The smell hadn’t changed either. A blend of wood, cloth and paper. You either got used to it at once or handed in your notice within days.

He went to his desk, booted up his computer and tried to access the Internet.

‘This page cannot be displayed. There may be technical problems, or you should check your browser settings.’

He clicked on the address line and typed:

www.orf.at

‘This page cannot be displayed.’

www.cnn.com

‘This page cannot be displayed.’

www.rtl.de

‘This page cannot be displayed. Try the following: Click on “update” or repeat the procedure later.’

The old floorboards creaked beneath his feet as he toured the offices once more, closely scrutinising them for something that hadn’t been there on Friday evening. He picked up Martina’s phone and dialled a few stored numbers. Answering machines only. He blurted out some incoherent messages followed by his phone number. He had no idea who he was speaking to.

He went to the kitchenette, took a can of lemonade from the fridge and drained it in one.

After the final swallow he swung round abruptly.

No one there.

He removed another can from the fridge without taking his eyes off the door. This time he paused between swallows and listened, but all he could hear was the lemonade fizzing in the can.

Please call me ASAP! Jonas

He stuck the Post-it on Martina’s computer screen and hurried to the exit without checking the other offices again. It was a spring lock, so he didn’t bother to double lock the door. He ran down the stairs three at a time.

*

For years his father had been living in Rüdigergasse, in the 5th District. Jonas liked the area but had taken an instant dislike to the flat, which was too dark and too overlooked. He loved to look down on the city from above. His father didn’t mind passers-by gawping at him in his living room. It’d been like that before and he was used to it. Besides, he’d wanted to make things easier for himself since his wife’s death. The flat was a few steps from a supermarket and there was a GP’s surgery on the floor above.

On his way into the 5th District, Jonas had an idea: why not make a racket? He honked his horn as if he were in a wedding convoy. The speedo needle quivered on twenty. The engine stuttered.

Some streets he drove along twice. He looked left and right to see if a door or a window opened. It took him almost half an hour to cover the short distance to the flat.

He stood on tiptoe and peered through his father’s window. The light was off. So was the TV.

He inspected the street, taking his time. This car’s wheels were touching the kerb, that one was parked further out. A bottle protruded from a dustbin, the plastic cover on a bicycle saddle flapped gently in the breeze. He counted the motorbikes and mopeds outside the building. He even tried to memorise the position of the sun. Only then did he get out his duplicate key and open the front door.

‘Dad?’

Quickly, he locked the door behind him and turned on the light.

‘Dad, are you there?’

He called before he entered every room, trying to make his voice sound deep and forceful. From the lobby he went into the kitchen, then back through the hallway and into the living room. Next, the bedroom. He didn’t forget the bathroom and toilet. He even stuck his head into the larder, with its chill smell of fermentation, of apples and cabbage.

His father, an inveterate collector and hoarder who spread butter on mouldy bread and heated up out-of-date tins in a double saucepan, was not there any more.

Like everyone else.

And, like everyone else, he’d left no clue behind. The whole place looked as if he’d just gone out. Even his reading glasses were lying in their usual place on top of the TV.

In the fridge Jonas found a jar of pickled gherkins that still looked edible. There wasn’t any bread, but he unearthed a packet of rusks in the kitchen cupboard. They would have to do. He didn’t feel like opening the larder door again.

While eating he tried, without much hope, to get a TV channel. He couldn’t entirely dismiss the possibility, because it had occurred to him that his father’s set was connected to a satellite dish. Perhaps only the cable network was affected, in which case some TV channels should be accessible via satellite.

Snow.

*

In the bedroom his father’s old wall clock was steadily beating time. He rubbed his eyes and stretched.

He looked out of the window. Nothing had changed as far as he could tell. The piece of plastic was still flapping in the breeze. None of the cars had moved. The sun was hovering in its accustomed place and seemed to be on course.

Jonas hung his shirt and trousers on a coat hanger. He listened once more for any sound other than that of the clock. Then he slid beneath the bedclothes. They smelt of his father.

*

Semi-darkness. At first, he didn’t know where he was.

In the half-sleep that preceded his awakening, the ticking of the clock, a sound familiar to him since his childhood, had lulled him into the false belief that he was in a different place at a different time. He had heard it ticking as a child while lying on the sofa in the living room, where he was meant to take his afternoon rest. He seldom closed his eyes, just daydreamed until his mother came to wake him with a mug of cocoa or an apple.

He turned on the bedside light. Half-past five. He’d slept for over two hours. The street was so narrow and the sun so low in the sky that its rays were illuminating only the upper floors of the buildings across the way. Inside the flat it was like late evening.

He shuffled into the living room in his underpants. It looked as if someone had just left. As if they’d tiptoed out so as not to wake him. He could positively sense that someone’s lingering imprint on the flat.

‘Dad?’ he called, knowing he wouldn’t get an answer.

While dressing he looked out of the window. The piece of plastic. The motorbikes. The bottle in the dustbin.

No change of any kind.

*

Back home he found some tinned food in the kitchen cupboard. While the plate was rotating in the microwave he wondered when he would go to a restaurant again. He watched the countdown on the display. Another sixty seconds. Another thirty, twenty, ten.

He eyed the food, hungry but with no appetite. Covering the plate with some foil, he shoved it aside and went over to the window.

Below him lay the Brigittenauer embankment. His view of the cloudy, softly gurgling waters of the Danube Canal

was partly obscured by a row of lush, luminous green trees. Looming up on the far side were the trees that flanked the Heiligenstädter embankment. The two big Ö3 logos on the roof of the radio station continued to revolve as usual on the right of the BMW building. On the skyline the city was bounded by the wooded local mountains: the Hermannskogel, Dreimarkstein and Exelberg. And soaring above the Kahlenberg, where Jan Sobieski had gone into battle against the Turks over three centuries earlier, was the huge television mast.