Nightblind (2 page)

Authors: Ragnar Jónasson

Tags: #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #British Detectives, #International Mystery & Crime, #Police Procedurals, #Thrillers & Suspense, #Crime, #Murder, #Suspense, #Literature & Fiction, #Contemporary Fiction, #Crime Fiction, #Noir, #Traditional Detectives, #Thrillers

RAGNAR JÓNASSON

translated by Quentin Bates

To Natalía, from Dad

The events of

Nightblind

take place approximately five years after

Snowblind

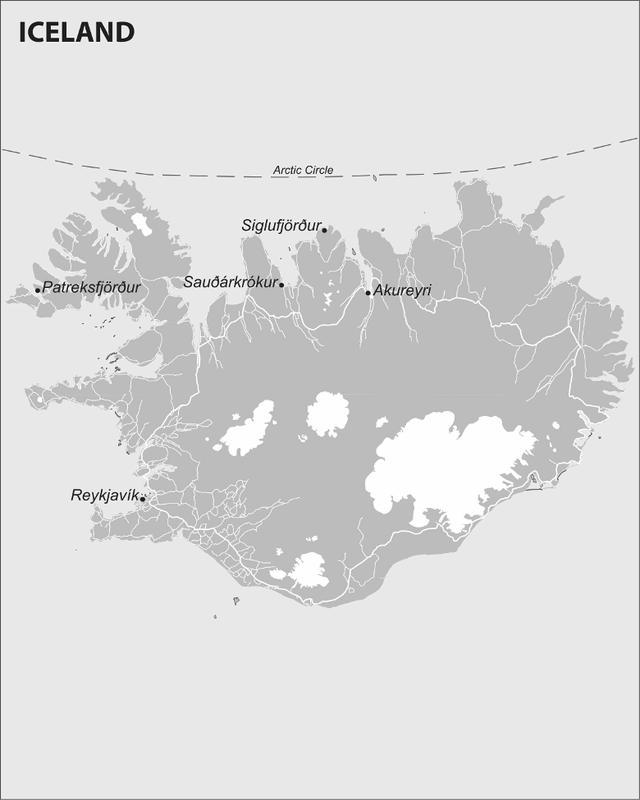

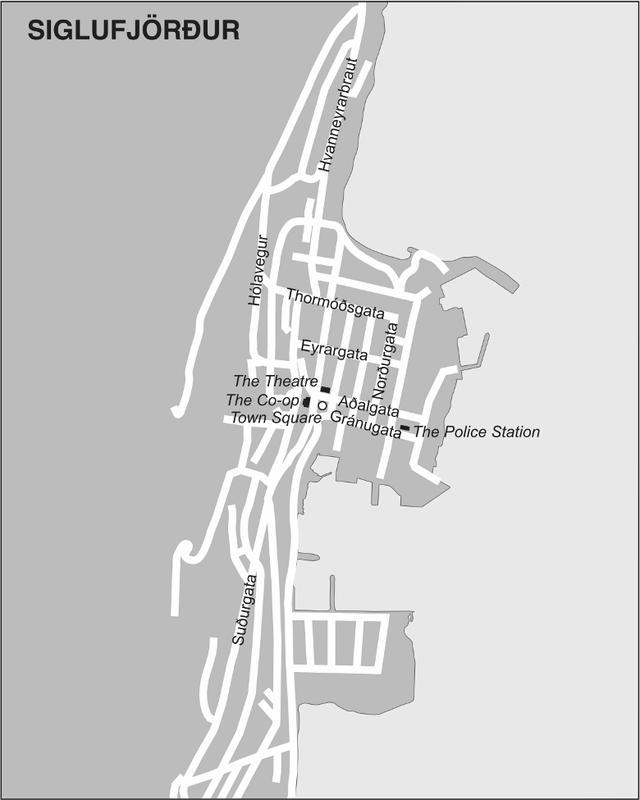

. Ari Thór Arason is still working as a police officer in the small town of Siglufjördur. Tómas, his boss, has moved down south, to the capital city of Reykjavík. The new inspector is a man called Herjólfur. Ari Thór has been reunited with his girlfriend Kristín, and they now have a ten-month-old son.

The next book in the series,

Blackout

, picks up the story again directly after the events of

Snowblind

, with the following two books set to complete the series of events linking

Snowblind

and

Nightblind

.

Something goes astray

In men and weather,

Men and words…

From the poem ‘Broken’, by Þorsteinn frá Hamri

(Skessukatlar, 2013)

Unsettling.

Yes, that’s the word. There was something unsettling about that ancient, broken-down house. The walls were leaden and forbidding, especially in this blinding rain. Autumn felt more like a state of mind than a real season here. Winter had swiftly followed on the heels of summer in late September or early October, and it was as if autumn had been lost somewhere on the road north. Herjólfur, Siglufjördur’s police inspector, didn’t particularly miss it, at least not the autumn he knew from Reykjavík, where he had been brought up. He had come to appreciate the summer in Siglufjördur, with its dazzlingly bright days. He enjoyed the winter as well, with its all-enveloping darkness that curled itself around you like a giant cat.

The house stood a little way from the entrance to the Strákar tunnel and as far as Herjólfur had been able to work out, it was years since anyone had lived in the place, located some distance from where the town proper hugged the shoreline. It looked as if it had simply been left there for nature’s heavy hands to do as she wished with the place, and her handiwork had been brutal.

Herjólfur had a special interest in this abandoned building and it was something that worried him. He was rarely fearful, having trained himself to push uncomfortable feelings to one side, but this time he’d been unsuccessful, and he was far from happy. The patrol car was now parked by the side of the road, and Herjólfur was hesitant to leave it. He shouldn’t even have been on duty, but Ari Thór, the town’s other police officer, was down with flu.

Herjólfur sat still for a moment, the patrol car lashed by the bitter chill of the rain. His thoughts travelled to the warm living room at home. Moving up here had been something of a culture shock, but he and his wife had managed to make themselves comfortable, and their simple house had been gradually transformed into a home. Their daughter was at university in Reykjavík; their son had remained with his parents, living in the basement and attending a local college.

Herjólfur had a few days’ holiday coming up, assuming Ari Thór was fit to return to work. He had been planning to surprise his wife with a break in Reykjavík. He had booked flights from Akureyri and secured a couple of theatre tickets. This was the type of thing he tried to make a habit, to take a rest from the day-to-day routine whenever the opportunity presented itself. Now, in the middle of the night, and while he was still on duty, he fixed his mind on the upcoming trip, as if using it as a lifeline to convince himself that everything would be fine when he entered the house.

His mind wandered back to his wife. They had been married for twenty-two years. She had become pregnant early in the relationship, and so they were married soon after. There hadn’t been any hesitation or, indeed, choice. The decision wasn’t anything to do with faith, but more with the traditions of decency to which he clung. He had been properly brought up – a stern believer in the importance of setting a good example. And they were in love, of course. He’d never have married a woman he didn’t love. Then their daughter was born and she became the apple of his eye. She was in her twenties now, studying psychology, even though he had tried to convince her to go in for law. That was a path that could have brought her to work with the police, connected in some way to the world of law and order; his world.

The boy had come along three years later. Now he was nineteen, a stolid and hard-working lad in his final year at college. Maybe he’d be the one to go in for law, or just apply straight to the police college.

Herjólfur had done his best to make things easier for them. He

had plenty of influence in the force and he’d happily pull strings on their behalf if they decided to choose that kind of future; he was also guiltily aware that he was often inclined to push a little too hard. But he was proud of his children and it was his dearest hope that they would feel the same about him. He knew that he had worked hard, had pulled himself and his family up to a comfortable position in a tough environment. There was no forgetting that the job came with its own set of pressures.

The family had emerged from the financial crash in a bad way, with practically every penny of their savings having gone up in smoke overnight. Those were tough days, with sleepless nights, his nerves on edge and an unremitting fear that cast a shadow over everything. Now, at long last, things seemed to have started to stabilise again; he had what appeared to be a decent position in this new place, and they were comfortable, even secure. Although neither of them had mentioned it, he knew that Ari Thór had applied for the inspector’s post as well. Ari Thór had a close ally in Tómas, the former inspector at the Siglufjördur station, who had since moved to a new job in Reykjavík. Herjólfur wasn’t without connections of his own, but Tómas’s heartfelt praise of and support for Ari Thór hadn’t boded well. And yet, the post had gone to him and not to Ari Thór – a young man of whom Herjólfur still hadn’t quite got the measure. Ari Thór had not proved to be particularly talkative and it wasn’t easy to work out what he was thinking. Herjólfur wasn’t sure if there was a grudge there over the way things had turned out. They hadn’t been working together for long. Ari Thór’s son had been born at the end of the previous year, on Christmas Eve, and he had gone on to take four months’ paternity leave plus a month’s holiday. They weren’t friends or even that friendly, but it was still early days.

Herjólfur’s senses sharpened, and all thoughts of his colleague were pushed from his mind as he stepped out of the car, and gradually approached the house. He had that feeling again.

The feeling that something was very wrong.

If it came to it, he reckoned he could easily hold his own with one man; two would be too much for him now that age had put paid to the fitness of his earlier years. He shook his head, as if to clear away ungrounded suspicions. There was every chance the old place would be empty. He was surprised at his discomfort.

There was no traffic. Few people found reason to travel to Siglufjördur at this time of year, least of all in the middle of the night and in such foul weather. The official first day of winter, according to the old Icelandic calendar, was next weekend, but that would only confirm what everyone already knew up here in the north – winter had arrived.

Herjólfur stopped in his tracks, suddenly aware of a beam of light – torchlight? – inside the old building. So there

was

someone there in the shadows, maybe more than one. Herjólfur was becoming increasingly dubious about this call-out and his nerves jangled.

Should he shout and make himself known, or try unobtrusively to make his way up to the house and assess the situation?

He shook his head again, and pulled himself together, striding forward almost angrily.

Don’t be so soft. Don’t be so damned soft!

He knew how to fight and the intruders were unlikely to be armed.

Or were they?

The dancing beam of light caught Herjólfur’s attention again and this time it shone straight into his eyes. Startled, he stopped, more frightened than he dared admit even to himself, squinting into the blinding light.

‘This is the police,’ he called out, with as much authority as he could muster, the quaver in his voice belying his bravado. The wind swept away much of the strength he’d put into his words, but they must have been heard inside, behind those gaping window frames.

‘This is the police,’ he repeated. ‘Who’s in there?’

The light was directed at him a second time and he had an overwhelming feeling that he needed to move, to find some kind of refuge. But he hesitated, all the time aware that he was acting against his own instincts. A police officer is the one with authority,

he reminded himself. He shouldn’t let himself be rattled, feel the need to hide.

He took a step forward, closer to the house, his footsteps cautious.

That was when he heard the shot, deafening and deadly.