Nimitz Class (45 page)

Authors: Patrick Robinson

“Well, I think we should vanish from sight an hour north of the Bosporus. Just so no one has the slightest idea where we are. The Turks will see us come through on the surface, but as the light starts to fade, we will disappear.

“Then, I’d like to be at our Black Sea station, set up and ready, periscope depth, just before dark, around 1930, about thirty-five miles north of the Bosporus entrance. Just so we have enough light to identify a freighter making ten knots in the correct direction, hopefully going right through to the Med.

“We’ll get in behind him. Then we can snort down to the entrance, at PD, get a good charge into the battery, and hope the merchantman doesn’t see us. He probably won’t, because the light will have gone completely within a half hour of our picking him up. With a bit of luck.”

Bill shook his head, and smiled. “Guess I’m talking to the von Karajan of the deep.”

“Who’s he?” grunted the admiral. “U-boats?”

“No, sir. He’s the conductor on the CD Laura sent me. One of the best ever. Maestro Herbert von Karajan.”

“Oh yes, I see. Of course. I’m not much good at opera, really. But it’s good of you to say so, even though it’s not true. I’m just a retired officer volunteering for a job no one else wants.”

“As the personal choice of the Flag Officer of the entire Royal Navy Submarine Service, sir.”

“Yes. Of course, I used to be his boss, too. He’s probably trying to get his own back.”

Dinner was subdued. The topic of conversation was anchored in their own anxieties about the perilous task they faced tomorrow. Bill had never been involved in a crash-stop in a submarine, and he finally summoned the courage to ask the admiral how it worked. He did not mention the real question he wanted to ask—what do we have to do to avoid slamming right into the freighter’s massive propellers?

“It’s only dramatic if you’re not ready,” replied the admiral. “Which makes your sonar team even more critical than usual. They have one vital task—to issue instant warning of any speed change, the slightest indication that the freighter is reducing its engine revolutions.

“Which means they have to keep a close check on the freighter’s props. If she slows, we’re talking split seconds, otherwise we

will

charge right into her rear end, which is apt to be rather bad news.

“If the water’s deep enough, we will slow down, dive, and try to duck right under him. If it’s not, and there’s a bit of room out to the side, we’ll go for the gap. If there’s not enough water, no room to the side, and we’re late slowing down, I think you’ll probably end up at Jeremy Shaw’s court-martial. If any of us survive it, that is.”

“Christ,” said Bill. “Are there any procedures I ought to know about if we have to stop in a hurry?”

“There are a couple of things. All the time we are close to the freighter, we will want to be at diving stations. But we must be on top-line to shut down to a specially modified collision station.

“None of us knows much about the water density changes, and we have no idea if we’ll be in vertical swirls. So we may need old-style trimming parties. That means our watertight doors have to be open for them at all times, so the men can go for’ard or aft at high speed to help keep the boat level.

“I have had several talks with Jeremy Shaw, and I have recommended he posts bulkhead sentries throughout. Everyone will be on

permanent standby. However, when we broadcast ‘crash-stop,’ the bulkhead doors will not be shut and clipped. They’ll be open for the trimming parties.”

Bill chewed his kebab thoughtfully, and then took a long swallow of red Turkish wine. He had never operated in a diesel-electric submarine, but he knew the basic collision procedures. In any tricky situation, the bulkhead doors should be kept shut and clipped in order to contain fire, or onrushing water if the submarine crashes or is holed. He knew too the terrifying dangers, especially if they were running deep.

The admiral remained sanguine, chatting away cheerfully about hair-raising scenarios below the surface of the Bosporus. “Actually, Bill, I’m hoping we’ll get a bit of practice quite early on if the freighter stops to pick up a pilot at the northern end. We’ll be right up his backside at that point, with the current sweeping us down the channel. Then we’ll find out how quick we are, and how easy it is to hold the trim, when two and a half thousand tons of steel traveling at ten knots suddenly slows down.”

Bill took another swig of wine, and they remained in the dining room for only another few minutes before returning to their rooms and turning in for the night. “Possibly my last night,” Bill said as he shut and clipped the bulkhead door of room 1045.

He opened the CD pack, and took out the two slim, sealed plastic holders and the glossy libretto booklet. No obvious message there. No note from Laura. He tipped up the outer box. Nothing there either. Then he began to leaf through the booklet.

He found it stapled to page 105. It read very simply:

I am back in Edinburgh now, and feeling a bit desolate not being able to talk to you. Please, Bill, look after my father, and for God’s sake look after yourself. I don’t think I could bear it if anything should happen to you both.

She signed it,

“Laura”

and placed a small line of three crosses beneath her signature.

But beneath the note were greater depths. Outlined in a pink highlighter were three lines sung by Carmen in the divine duet with Carreras during the ninth scene of Act One—translated from the French: “

It’s not forbidden to think! I’m thinking of a certain officer who loves me, and whom in my turn, I might very well love!”

“That Bizet,” said Bill. “A guy with real perception.”

After a night disturbed by nerve-racked dreams, he felt unaccountably full of energy when finally he packed his bag and headed downstairs to meet the admiral. He paid both accounts with a credit card, and they headed down to the docks in a cab.

The ride out through the harbor, south along the Sea of Marmara, afforded them a spectacular view of Istanbul, the great pointed minarets of the Blue Mosque, Hagia Sophia, and the Topkapi Palace. The specter of the giant Bogazi Road Bridge, which spans the Bosporus three miles upstream from the Golden Horn, shimmered in a light heat-mist this morning as cars streamed across, two hundred feet above the water.

The captain of HMS

Unseen

held her stationary in the current just north of the Turkish Naval anchorage on the Asian bank. In flat, calm water Bill Baldridge, the admiral, and the pilot made their ship-to-ship transfer, bags being hauled by sailors with hooked ropes.

Both officers and the Turkish pilot expertly climbed the rope ladder, and were helped up onto the casing by two brawny young lieutenants. The newcomers joined Lieutenant Commander Jeremy Shaw on the bridge for the surface ride north through the Bosporus.

The CO greeted Admiral MacLean with the due deference Bill Baldridge had witnessed in all of his travels. He was more welcoming to Bill, and briefly outlined the high points of the long journey out from Barrow-in-Furness to Turkey. He was pleased with the submarine, and the crew had easily mastered the systems in the two-week workup period before they left England. It usually takes five weeks, but of course on this occasion they had not had to bother with weapons.

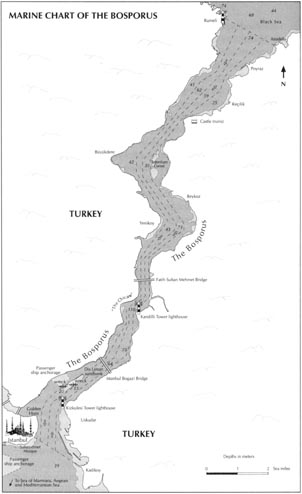

The ride north was highly instructive. Admiral MacLean assessed the width of the channel, the lights on the two big bridges,

particularly those on the much narrower one, three miles north of the Bogazi, the Fatih Sultan Mehmet, already nicknamed by

Unseen

’s crew as the “Fatty Sultan.”

He noted the water depths in the narrow right-left “chicane” immediately south of the bridge, marked by the navigation control station at Kandilli, on the Asian side. The first big corner they would meet, a hard left and then a hard right, was equally as dangerous because the channels narrowed dramatically. The admiral took notes in small neat handwriting: “

two bloody great shoals to port, five meters only

.”

The sunlit waters of the Bosporus seemed wide on the surface, and not at all menacing. Only the charts revealed the hazardous nature of the seabed below. All the way north, Admiral MacLean was trying to establish the treacherous shape of the underwater contours.

Two hours after they set sail,

Unseen

cleared the Bosporus, and the men on the bridge said good-bye to the disembarking pilot. Then Captain Shaw ordered a northerly course, zero-three-zero, across a calm sea to their waiting point.

At 1730, Captain Shaw decided they should vanish: “Officer of the Watch, dive the submarine.”

“Aye, aye, sir.”

“Clear the bridge.”

“Upper lid shut, one clip…both clips on.”

“Open main vents…Group up…half ahead main motor.”

“Main vents open, sir…Telegraph to half ahead…Group up, sir.”

“Five down. Seventeen and a half meters.”

“Twelve meters, sir.”

“Ease the bubble, Cox’n.”

“Eighteen meters. Bubble forward, sir.”

“Very good. Shut main vents. Group down.”

“Up ESM…particularly looking for commercial X-band radars coming in from the north, say three-one-five to zero-four-five.”

“Looks a pretty good trim,” said Captain Shaw. “I want you to

stay in this position while we find a merchantman heading for the Bosporus. He’ll want to be under ten knots. An eight-knotter will do us fine. Stay reasonably furtive. Though he won’t be looking for the likes of us. Tell me if you get one, please.”

“Aye, sir. Blue watch…watch diving…patrol quiet state.”

“I’ll be in the wardroom with the admiral and our American guest. You have the ship, Number One.”

“I have the ship, sir.”

The Commanding Officer, the admiral, and Lieutenant Commander Baldridge immediately retired to the wardroom for a conference.

“The bottom’s mostly marked as shingle, Admiral,” the C.O. said. “We don’t want to be stern-down if we hit it. The trimming parties are going to be very important to us. But I can’t help feeling that in the narrows a lot of that shingle will turn out to be rock, which could be very nasty. Thus, I intend to stay at periscope depth, at almost any cost, well outside normal rules.”

“I think you need my written approval for that, Jeremy,” said Admiral MacLean. “I’ll enter it in the log. But I do agree with you—it’d be much better to write off a periscope on the bottom of a freighter, than leave yourself with a bloody great rock shoved straight through the hull.”

The three men stared at the chart. Jeremy Shaw was frowning, and said suddenly, “The tricky bits are here…here…and here.” He pointed to the big sharp bends with his index finger. We are going to call them Tattenham Corner—after the left-hander on the English Derby racecourse—and the Chicane. Usual reasons. Men under a lot of pressure often react faster to familiar words. These places are all unpronounceable Turkish, and represent mass confusion to everyone.”

“Good idea,” said the admiral.

“On the left-handers here I expect our leading freighter to keep right and not cut the corners. But he may be tempted to do so if there’s nothing coming up the other way. If he stops or does something bloody silly, and I can’t stop, or get under him, I’ll evade to port. And that’s when we may have to correct trim in a big hurry.”

“Yes, Jeremy. But if we have to evade, and there is a queue coming up the other way, I think we’d be better to surface astern of him, for a bit more control. You never know, he might not even notice. Amazing what you can get away with if you have enough brass nerve.”

“Yes,” Bill chimed in. “I once heard of a really insolent British warship getting right up to one of our carriers disguised as a curry-house.”

Jeremy Shaw burst out laughing. The admiral feigned innocence. “What about depths, Jeremy?” he said.

“Well, sir, we need seventeen and a half meters to run at periscope depth, plus five meters below…about twenty-two and a half meters minimum. The worst bit, easily, is right below the Bogazi Bridge, where the chart shows twenty-seven meters, but there’s a couple of wrecks marked right in the middle of the channel, one of ’em only fifteen meters below the surface.

“Right there, I can’t go to the right, because of the mooring buoys, and the merchant-ship anchorage. I can’t go down the middle because of the wrecks, and I can’t go left, because you can’t see round the big bend. This makes the other lane very, very dangerous. Not least because it’s only thirty meters deep anyway, which would prevent us ducking under a big oncoming freighter.

“If our leader looks as if he’s going to drive straight over the wrecks, I think we’ll

have

to surface, for a half-mile, only three minutes. Trouble is, it’ll be damned bright up there from the shore lights. That’s where the Turks might spot us.”

“I suppose we’ll just have to keep our fingers crossed, then,” said Sir Iain. “And hope for the bloody best. By the way, have you got a personal list of ‘call off’ factors, Jeremy? Like visibility, etc.”

“Just the usual things, sir. Defects on the nav system, losing our leader early on, before the last narrows, the Turks making it damned obvious they’ve seen us, or if trimming the ship is just too damned difficult in the currents. Aside from those, anything sudden, unexpected, which takes us beyond the last limit of our already-stretched margins for error.