Nineteen Seventy-Seven: The Red Riding Quartet, Book Two (21 page)

Read Nineteen Seventy-Seven: The Red Riding Quartet, Book Two Online

Authors: David Peace

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Police Procedural

270 Oldham Street, dark and rain-stained, rotting black bin bags heaped up outside, MJM Publishing sat on the third floor.

I stood at the foot of the stairs and shook down my raincoat.

Soaked through, I walked up the stairs.

I banged on the double doors and went inside.

It was a big office, full of low furniture, almost empty, a door to another office at the back.

A woman sat at a desk near the back door, a bag, typing.

I stood at the low counter by the door and coughed.

Yes? she said, not looking up.

Id like to talk to the proprietor please?

The what?

The owner.

Who are you?

Jack Williams.

She shrugged and picked up the old telephone on her desk: Theres a man here wants to see the owner. Names Jack Williams.

She sat there, nodding, then covered the mouthpiece and said, What do you want?

Business.

Business, she repeated, nodded again, and asked, What kind of business?

Orders.

Orders, she said, nodded one last time, and then hung up.

What? I said.

She rolled her eyes. Leave your name and number and hell call you back.

But Ive come all way over from Leeds.

She shrugged her shoulders.

Bloody hell, I said.

Yep, she said.

Can I at least have his name?

Lord High and Bloody Mighty, she said, ripping the piece of paper out of the typewriter.

I went for it: Dont know how you can work for a bloke like that.

I dont intend to for much longer.

You out of here then?

She stopped pretending to work and smiled, Week next Friday.

Good on you.

I hope so.

I said, You want to earn yourself a couple of quid for your retirement?

My retirement? Youre no spring chicken yourself, you cheeky sod.

A couple of quid to tide you over?

Only a couple?

Twenty?

She came over to the front of the office, a little smile. So who are you really?

A business rival, shall we say?

Say what you bloody well want for twenty quid.

So youll help me out?

She glanced round at the door to the back office and winked, Depends what you want me to do, doesnt it?

You know your magazine

Spunk?

She rolled her eyes again, pursed her lips, and nodded.

You keep lists of the models?

The

models!

You know what I mean.

Yeah.

Yeah?

Yeah.

Addresses, phone numbers?

Probably, if they went through the books but, believe me, I doubt they all did.

If you could get us names and anything else on models thatd be great.

What you want them for?

I glanced at the back office and said, Look, I sold a job lot of old

Spunks

to Amsterdam. Got a bloody bomb for them. If your Lordship is too busy to earn himself a cut, then Ill see if I cant set myself up.

Twenty quid?

Twenty quid.

She said, I cant do it now.

I looked at my watch. What time you finished?

Five.

Bottom of stairs at five?

Twenty quid?

Twenty quid.

See you then.

I stood in a red telephone box in the middle of Piccadilly Bus Station and dialled.

Its me.

Where are you?

Still in Manchester.

What time you coming home?

Soon as I can.

Ill wear something pretty then.

Outside, the rain kept falling, the red box leaking.

Id been here before, this very box, twenty-five years before, my fiancée and I, waiting for the bus to Altrincham to see her Aunt, a new ring on her finger, the wedding but one week away.

Bye, I said, but shed already gone.

I stepped back into the sheets of piss and walked about Piccadilly for a couple of hours, going in and out of cafés, sitting in damp booths with weak coffees, waiting, watching skinny black figures dancing through the rain, the lot of us dodging the raindrops, the memories, the pain.

I looked at my watch.

It was time to go.

Going up to five, I found another telephone box on Oldham Street.

Anything?

Nothing.

At five to five I was huddled at the bottom of the steps, ringing wet.

Ten minutes later she came down the stairs.

Ive got to go back up, she said. Im not finished.

Did you get the stuff?

She handed me an envelope.

I glanced inside.

She said, Its all there. What there is.

I believe you, I said and handed her twenty folded quid.

Pleasure doing business with you, she laughed, walking back upstairs.

Bet it was, I said. Bet it was.

I went down to Victoria where they told me the Bradford train went from Piccadilly.

I ran up through the cats and the dogs and caught a cab for the last bit.

It was almost six when we got there, but there was a train on the hour and I caught it.

Inside, the carriage stank of wet clothes and stale smoke and I had to share a table with an old couple from Pennistone and their sweating sandwiches.

The woman smiled, I smiled back and the husband bit into a large red apple.

I opened the envelope and took out tissue-thin pieces of duplicate paper, three in all.

There were lists of payments, cash or cheque for February 1974 through to March 1976, payments to photoshops, chemists, photographers, paper mills, ink works, and models.

Models

.

I ran down the list, out of breath: Everything stopped, dead.

Everything stopped, dead.

Clare Morrison

, known to be Strachan.

Everything stopped.

I took out Oldmans memo:

Jane Ryan

, read Janice.

Everything

Sue Penn

, read Su Peng.

Stopped

Read Ka Su Peng.

Dead.

There on that train, that train of tears, crawling across those undressed hells, those naked little hells, those naked little hells all decked out in tiny, tiny bells, there on that train listening to those bells ring in the end of the world:

1977.

In 1977, the year the world broke.

My world:

The old woman across the table finishing the last sandwich and screwing up the silver foil into a tiny, tiny ball, the egg and cheese on her false teeth, crumbs stuck in the powder on her face, her face smiling at me, a gargoyle, her husband bleeding his teeth into that big red apple, this big red, red, red world.

1977.

In 1977, the year the world turned red.

My world:

I needed to see the photographs.

The train crawled on.

I had to see the photographs.

The train stopped at another station.

The photographs, the photographs, the photographs.

Clare Morrison, Jane Ryan, Sue Penn

.

I was crying and I wanted to stop, wanted to pull myself together but, when I tried, the bits didnt fit.

Pieces missing.

1977.

In 1977, the year the world fell to bits.

My world:

Going under, to the sea-bed, better off dead, that evil, evil bed, those secret underwater waves that floated me up bloated, up from the sea-bed.

Beached, washed up.

1977.

In 1977, the year the world drowned.

My world:

1977 and I needed to see the photographs, had to see the photographs, the photographs.

In 1977, the year

1977.

My world:

An imagined photograph.

Wear something pretty

I didnt stop in Bradford, just changed trains for Leeds and sat on another slow train through hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell, hell:

Hell.

In Leeds I ran through the black rain along Boar Lane, stumbling, through the precinct, tripping, on to Briggate, falling, into Joes Adult Books.

Spunk?

Back issues?

By the door.

You got every issue?

I dont know. Have a look.

On my knees, through the pile, stacking doubles to one side and holding on to every different issue I came to, clutching their plastic wrappings.

This it?

Maybe some in the back.

I want them.

All right, all right.

All of them.

I stood there while Joe went into the back, stood there in the bright pink light, the cars outside in the rain, the blokes browsing, giving it to me sideways.

Joe came back, six or seven in his hands.

That it?

You must have them all.

I looked down and saw Id got a good thirteen or fourteen.

It still going?

No.

How much?

He tried to take them from me but then said, How many you got there?

I counted, dropping them and then picking them up, until I said, Thirteen.

Eight forty-five.

I handed him a tenner.

You want a bag?

But I was gone.

In the Market toilets, the cubicle door locked, on the floor, ripping open plastic bags, tearing through the pages, through the pictures and the photographs, the photographs of bums and tits, cunts and

cuts,

the hairy bits, the dirty bits, the bloody, bloody red bits, until I came came to the yellow bits.

This is why people die.

This is why people.

This is why.

I stood upright in another box and dialled.

George Oldman, please.

Whos calling?

Jack Whitehead.

Just a moment.

I stood and waited inside the box.

Mr Whitehead?

Yes.

Assistant Chief Constable Oldmans office is not accepting any more calls from the press. Could you please call Detective Inspector Evans on

I hung up and puked down the inside of the red telephone box.

On my bed, a bed of paper and pornography, in prayer, the telephone ringing and ringing and ringing, the rain against the windows falling and falling and falling, the wind through the frames blowing and blowing and blowing, the knocks on the door knocking and knocking and knocking.

What happened to our Jubilee?

Its over.

To remission and forgiveness, an end to penance?

I cant forgive the things I dont even know

I do, Jack. I have to.

The telephone was ringing and ringing and ringing and she was still beside me on the bed.

I lifted up her head to free my arm, to stand.

Barefoot, I went to the telephone.

Martin?

Jack? Its Bill.

Bill?

Christ, Jack. Where you been? All bloody hells broken loose.

I stood there in the dark, nodding.

Turns out the dead prostitute in Bradford, its only Frasers bloody girlfriend and that its him theyre holding.

I looked back over at the bed, at her still on the bed.

Jane Ryan

, read Janice.

Bill was saying, Then Bradford got a letter from Ripper and they didnt say anything to Oldman or anyone and theyve only gone and fucking printed it in the morning edition, and sold it on to

The Sun.

I stood there, in the dark.

Jack?

Fuck, I said.

Shit creek, mate. You better come in.

I dressed in the dawn light, the dim light, and left her still on the bed.

On the stairs, I looked at my watch.

It had stopped.

Outside, I walked down the road to the Paki shop on the corner and bought a

Telegraph & Argus

.

I sat on a low wall, my back in a hedge, and read:

RIPPER LETTER TO OLDMAN?

Yesterday morning the Telegraph & Argus received the following letter from a man claiming to be Yorkshires Jack the Ripper killer

.

Tests carried out by independent experts and information from reliable police sources lead us here at the Telegraph & Argus to believe that this letter is genuine, and not the first such letter this man has sent

.

We here at the Telegraph & Argus, however, believe the British Public should have the right to judge for yourselves.

From Hell

.

Dear George

I am sorry I cannot give my name for obvious reasons. I am the Ripper. Ive been dubbed a maniac by the Press but not by you, you call me clever cause you know I am. You and your boys havent a clue that photo in the paper gave me fits and that bit about killing myself, no chance. Ive got things to do. My purpose is to rid streets of them sluts. My one regret is that young lassie Johnson, did not know cause changed routine that nite but warned you and XXXX XXXXXXXXX at

Post.

Up to number five now you say, but theres a surprise in Bradford, get about you know

.

Warn whores to keep off streets cause I feel it coming on again

.

Sorry about young lassie.

Yours respectfully

Jack the Ripper

.

Might write again later I not sure last one really deserved it. Whores getting younger each time. Old slut next time hope

.

The next headline:

DID THE POLICE AND THE POST KNOW?

I sat on the low wall, bile in my mouth, blood on my hands, crying.

This is why people die.

This is why people.

This is why.

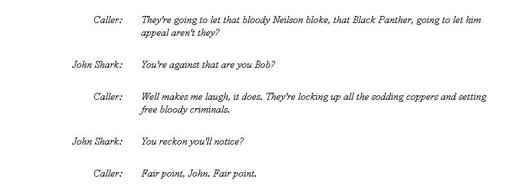

The John Shark Show

The John Shark Show

Radio Leeds

Tuesday 14th June 1977

Chapter 18

I open my eyes and say:

I didnt do it.

And John Piggott, my solicitor, stubs out his cigarette and says, Bob, Bob, I know you didnt.

So get me fucking out of here.

I close my eyes and say:

But I didnt do it.

And John Piggott, my solicitor, a year younger and five stone fatter, says, Bob, Bob, I know.

So why the fuck do I have to report to Wood Street bloody Nick every fucking morning?

Bob, Bob, lets just take it and get you out of here.

But this means they can just pick me up any fucking time they want, haul me back in here.

Bob, Bob, they can anyway. You know that.

But theyre not going to charge me?

No.

Just suspend me without pay and have me report in every fucking morning until they find a way to fit me up?

Yes.

The Sergeant on the desk, Sergeant Wilson, he hands me my watch and the coins from my trousers.

Dont be buying no tickets to Rio now.

I say, I didnt do it.

No-one said you did, he smiles.

So keep it fucking shut, Sergeant.

And I walk away, John Piggott holding the door open for me.

But Wilson calls after me:

Dont forget: ten oclock, tomorrow, Wood Street.

In the car park, the empty car park, John Piggott unlocks the car door.

Take a deep breath, he says, doing just that.

I get into the car and we go, Hot Chocolate on the radio again.

John Piggott pulls up on Tammy Hall Street, Wakefield, just across from the Wood Street Police Station.

Ive just to nip in and get something, he says and heads into the old building and up the stairs to his first-floor office.

I sit in the car, the rain on the windscreen, the radio playing, Janice dead, and I feel like Ive been here before.

She was pregnant

.

In a dream, in a vision, in a buried memory, I dont know which or where, but I know Ive been here before.

And it was yours

.

Where to? asks Piggott as he gets back in.

The Redbeck, I say.

On the Doncaster Road?

Yeah.

She lay down beside me on the floor of Room 27 and I felt grey, finished

.

I close my eyes and shes under them, waiting.

She stood before me, her cracked skull and punctured lungs, pregnant, suffocated

.

I open my eyes and rinse cold water over my face, down my neck, grey, finished.

John Piggott comes in with two teas and a chip sandwich.

It stinks out the room, the sandwich.

Fuck is this place? he asks, eyes this way and that.

Just somewhere.

How long you had it?

Its not really mine.

But you got the key?

Yeah.

Must cost a bloody fortune.

Its for a friend.

Who?

That journalist, Eddie Dunford.

Fuck off?

No.

I stepped out of the old lift and on to the landing

.

I walked down the corridor, the threadbare carpet, the dirty walls, the smell

.

I came to a door and stopped

.

Room 77

.

I wake and Piggotts still sleeping, wedged under the sink. I count coins and head out into the rain, collar up.

In the lobby, under the on/off strip lighting, I dial.

Speak to Jack Whitehead, please?

One moment.

In the lobby, under the on/off lighting, I wait, everything gone quiet.

Jack Whitehead speaking.

This is Robert Fraser.

Where are you?

The Redbeck Motel, just outside Wakefield on the Doncaster Road.

I know it.

I need to see you.

Likewise.

When?

Give us half an hour?

Room 27. Round the back.

Right.

In the lobby, under the on and the off, I hang up.

I open the door, Piggott awake, bringing a bucket of rain in with me.

Where you been?

Phone.

Louise?

No, and know I should have.

Who did you call?

Jack Whitehead.

From the

Post?

Yeah. You know him?

Of him.

And?

The jurys still out.

I need a friend, John.

Bob, Bob, you got me.

I need all the bloody ones I can get.

Well, watch him. Thats all.

Thanks.

Just watch him.

Theres a knock.

Piggott tenses.

I go to the door, say: Yeah?

Its Jack Whitehead.

I open the door and there he is, standing in the rain and the lorry lights, a dirty mac and a carrier bag.

You going to let me in?

I open the door wider.

Jack Whitehead steps into Room 27, clocking Piggott and then the walls:

Fuck, he whistles.

John Piggott sticks out his hand and says, John Piggott. Im Bobs solicitor. Youre Jack Whitehead, from the

Yorkshire Post?

Right, says Whitehead.

Have a seat, I say, pointing at the mattress.

Thanks, says Jack Whitehead and we all squat down like a gang of bloody Red Indians.

I didnt do it, I say, but Jacks having trouble keeping his eyes off the wall.

Right, he nods, then adds: Didnt think you did.

What have you heard? asks Piggott.

Jack Whitehead nods my way, About him?

Yeah.

Not much.

Like?

First we heard was thered been another murder, in Bradford, everyone over there saying it was a Ripper job, his lot saying nothing, next news theyd suspended three officers. That was it.

Then?

Then this? says Whitehead, taking a folded newspaper out of his coat and spreading it over the floor.

I stare down at the headline:

RIPPER LETTER TO OLDMAN?

At the letter.

Weve seen it, says Piggott.

Bet you have, smiles Whitehead.

A surprise in Bradford, I whisper.

Kind of puts you in the clear.

Youd think so, yeah, nods Piggott.

Whitehead says, You think it was the Ripper?

Who killed her? asks Piggott.

Whitehead nods and they both look at me.

I cant think of anything, except she was pregnant and now shes dead.

Both of them.

Dead.

Eventually I say, I didnt do it.

Well, Ive got something else. Another hat for the ring, says Whitehead and tips a pile of magazines out of his plastic carrier bag.

Fucks all this? says Piggott, picking up a porno mag.

Spunk

. You heard of it? Whitehead asks me.

Yeah, I say.

How?

Cant remember.

Well, you need to, he says and hands me a magazine open at a bleached blonde with her legs spread, mouth open, eyes closed, and fat fingers up her cunt and arse.

I look up.

Look familiar?

I nod.

Who is it? asks Piggott, straining at the upside-down magazine.

I say, Clare Strachan.

Also known as Morrison, adds Jack Whitehead.

Me: Murdered Preston, 1975.

What about her? You know her? he asks and hands me another woman, Oriental, black hair with her legs spread, mouth open, eyes closed, and thin fingers up her cunt and arse.

No, I say.

Sue Penn, Ka Su Peng?

Me: Assaulted Bradford, October 1976,

Give the boy a prize, says Whitehead quietly and hands me another magazine.

I open it.

Page 7, he says.

I turn to page 7, to the dark-haired girl with her legs spread, her mouth open, her eyes closed, a dick in her face and come on her lips.

Who is it? Piggotts asking.

Im sorry, says Jack Whitehead.

Piggott still asking: Who is it?

But the rain outside, its loud, deafening, like the lorry doors as they slam shut, one after another, in the car park, endlessly.

No food, no sleep, just circles:

Her cunt.

Her mouth.

Her eyes.

Her belly.

No food, no sleep, just secrets:

In her cunt.

In her mouth.

In her eyes.

In her belly.

Circles and secrets, secrets and circles.

I ask: MJM Publishing? You checked it out?

I was over there yesterday, says Whitehead.

And?

Your run-of-the-mill porn publisher. Slipped a disgruntled employee twenty quid for the names and addresses.

John Piggott asks, How did you find out about it?

Spunk?

Yeah.

An anonymous tip.

How anonymous?

Young lad. Skinhead. Said hed known Clare Strachan when she was calling herself Morrison and living over here.

I say, You got a name?

For him?

Yeah.

Barry James Anderson, and Id seen him before. Local. Hell be in the files.

I swallow;

BJ

.

What files? asks Piggott, playing catch-up, years behind.

Cant you have a word with Maurice Jobson, presses Whitehead, ignoring Piggott. The Owls taken you under his wing, hasnt he?

I shake my head. Doubt it now.

You told him anything about any of this?

After that last time we spoke, I went to him to get the files.

And?

Gone.

Fuck.

A Detective Inspector John Rudkin, my bloody boss, he checked them out in April 1975.

April 75? Strachan wasnt even dead then.

Yeah.

And he never brought them back?

No.

Not even after she did die?

Never even fucking mentioned them.

And you told Maurice Jobson all this?

He worked it out for himself when he tried to pull the files.

Which files? asks Piggott again.

Whitehead, foot down, ignoring him again: What did Maurice do?

Told me hed deal with it. Next time I saw Rudkin it was when they came and picked me up.

He say anything?

Rudkin? No, just took a fucking swing.

And hes suspended?

Yes, says Piggott, a question he can answer.

You spoken to him?

He cant, says Piggott. It was one of the stipulations of his release. No contact with DI Rudkin or DC Ellis.

What about Maurice?

Thats OK.

You should show him these, says Whitehead, pointing at the carpet of pornography before us.

I cant, I say.

Why not?

Louise, I say.

Your wife?

Yeah.

The Badgers daughter, smiles Whitehead.

Piggott: You going to tell me which fucking files youre talking about. I think I should know

Mechanically I say, Clare Strachan was arrested in Wakefield under the name Morrison in 1974 for soliciting, and was a witness in a murder inquiry.

Which murder inquiry?

Jack Whitehead looks up at the walls of Room 27, at the pictures of the dead, at the pictures of the dead little girls and says: Paula Garland.

Fucking hell.

Yeah, we both say.

Jack Whitehead comes back with three teas.

Im going to go see Rudkin, he says.

Theres someone else, I say.

Who?

Eric Hall.

Bradford Vice?

I nod, You know him?

Heard of him. Suspended, isnt he?

Yeah.

What about him?

Turns out he was pimping Janice.

And thats why hes suspended?

No. Peter Hunters mob.

And you think I should pay him a visit?

He must know something about these, I say, pointing at the magazines again.

You got home addresses for them?

Rudkin and Hall?

He nods and I write them out on a piece of paper.

You should talk to Chief Superintendent Jobson, Piggott is telling me.

No, I say.

But why? You said you need all the friends you can get.

Let me talk to Louise first.

Yeah, says Jack Whitehead suddenly. You should be with your wife. Your family

You married? I ask him.

Was, he says. A long time ago.

I stand in the lobby, under the on/off strip lighting, and I die:

Louise?

Sorry, its Tina. Is that Bob?

Yeah.

Shes at the hospital, love. Hes almost gone.

In the lobby, under the on/off lighting, I wait, everything gone.

Bob? Bob?

In the lobby, under the on and the off, I hang.