No Higher Honor (16 page)

Authors: Bradley Peniston

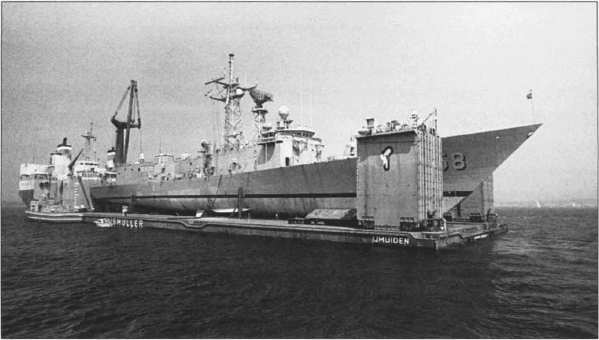

Roberts

was carried from Dubai to Newport, Rhode Island, aboard the semi-submersible heavy-lift ship

Mighty Servant 2

. Here, the frigate is ready for offloading in Narragansett Bay on 1 August 1988.

Photographer's Mate 2nd Class (SW) Jeff Elliott, U.S. Navy

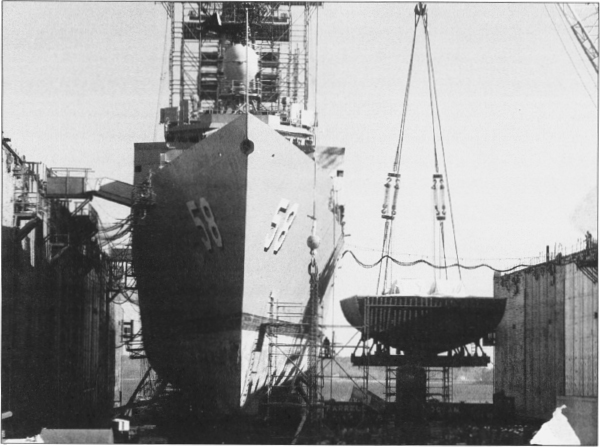

Roberts

's 310-ton replacement engine room module into the dry dock at Bath Iron Works' repair yard in Portland, Maine, ca. 1 December 1988.

Author's collection

Passage to Hormuz

O

ut in the Atlantic, the ships from Newport were soon joined by the guided missile cruiser USS

Wainwright

(CG 28), out of Charleston, South Carolina, and yet another frigate, USS

Jack Williams

(FFG 24), sailing from Mayport, Florida. Together, the quartet of warshipsâby happenstance, all four were products of Bath Iron Worksâmade up Destroyer Squadron 22 (DesRon 22). Their thirty-five-day journey to the Persian Gulf would require the transit of one ocean, three seas, three gulfs, three straits, and a canal. The time would be spent wisely, in preparation for the hazards that would confront them from their very first day in the Gulf.

The commodore of DesRon 22 was Capt. Donald A. Dyer, a gravel-voiced man with a dead-calm manner. He called himself the Redman, after the brand of chewing tobacco he kept in his cheek; even over the scratchy bridge radio, you could practically hear the juice dripping. No one ever heard the Redman get excited. Rinn had gotten to know Dyer during squadron workups off Puerto Rico. He found the commodore as demanding as he himselfâthough Dyer's controlled demeanor contrasted with the occasional explosion from Rinn. And the commodore did not hesitate to take the high-spirited skipper down a notch when necessary.

It had happened once during a large fleet exercise. The

Roberts

had passed a busy and successful couple of days, firing off a pair of missiles and completing numerous other assignments with the ship's usual competence and efficiency. Pressed for time to reach his next assignment, the captain sent a message to Dyer's staff, asking what the commodore intended for his ship and asking permission to depart. As time ticked away with no answer, Rinn jumped the chain of command and sought approval from the staff of the admiral who was running the exercise. This breached naval protocol. In his low voice, the commodore chewed

Rinn out over the radio, and followed it up the next day in writing. “Juniors ârequest' the assistance of their seniors, keep their seniors informed in a timely manner, think ahead, and are ready for flexible response,” Dyer wrote. “Asking you âyour intentions' is my prerogative. Change your tone.”

1

The episode set Rinn back on his heels. “Here I thought we were going to get praise for the good things we were doing,” he said later. Instead, the message was:

you're getting too big for your britches

. Rinn conceded almost immediately that he'd acted unprofessionally, and when the

Roberts

pulled into Mayport for inspections, he sent the commodore a meek blinking-light signal: “Quietly reporting for duty.”

Dyer laughed. “I just needed to get you back in the box,” Rinn recalled him saying. “You were running around doing great stuff, and it was clear that you had gotten to the point where you thought you were invincible, and you were going to get yourself in trouble.”

2

As DesRon 22 made its way across the Atlantic, Dyer kept his four ships on their toes by pitting them against one another in various drills. Glenn Palmer particularly loved the no-notice gunnery contests. The radio would squawk, “Quickdraw, quickdraw, quickdraw, bearing 270, main gun,” and the game would be on.

Deep in the

Roberts

's superstructure, gunner's mates hastened to load their 76-mm gun. Topside, the lookouts and officer of the deck snapped their heads around to ensure that the target area was clear. Down the ladder in CIC, the tactical action officer and his subordinates checked the radar screens, requested the captain's permission to fire, and let fly. Palmer's team, always good, got better. By the time the squadron passed through the Strait of Gibraltar, the

Roberts

could put five rounds down-range in twenty secondsâa very quick reaction.

But gunnery, the defining measure of a warship in an earlier era, had long ago surrendered its primacy among a ship's combat skills. Calls for naval gunfire were all but nonexistent these days. By contrast, the management of information was a crucial, round-the-clock occupation. Captain and crew sorted through a flood of oft-conflicting visual reports and electronic data to figure out what was going on around themâestablishing and maintaining situational awareness, as the military called it. The task had grown more complex with the introduction of radio

networks that shared sensor data between ships. A blip that appeared on one frigate's radar screen automatically appeared on every other warship on the netâin theory. In practice, the computers had a hard time figuring out when two ships were looking at the same aircraft. So sailors spent a lot of time on the radio with their counterparts in other ships, trying to figure out which blips were real. DesRon 22 practiced all the way across the Atlantic. “My job, basically the whole way over, was getting proficient at it,” said Rick Raymond, the sheet-metalworker-turned-operations-specialist.

3

Raymond and the others also learned a brand-new word:

deconfliction

, the process invented to keep Iraq's aircraft from shooting U.S. warships. After the

Stark

incident, American naval officers had visited Baghdad to develop a set of radio calls to ward off approaching Iraqi pilots. And when a missile-laden Mirage lifted from its air base, U.S. radio operators passed the word from ship to ship down the Gulf, like lighting signal fires along a mountain range.

Yet Dyer also endeavored to keep the mood light and the crews loose. “Give the skipper a haircut on the forecastle,” the Redman rumbled over the bridge-to-bridge circuit one day. On four American warships, sailors tumbled over themselves to roust their barbers, run an extension cord out onto the deck, and set clippers buzzing around their captains' heads.

The

Roberts

sonar operators were practicing new skills as well: mine hunting. There would be little call for their award-winning sub-hunting talents on this deployment, for no subs were known to operate in the shallow inland sea.

4

But in the past year, Gulf crews had spotted more than a hundred mines, drifting alone or laid in fields. So the sonar operators had been trained to fire the ship's machine guns at the floating weapons, and on the way over, they practiced shooting empty fifty-five-gallon drums rolled from the flight deck. “SBR has dropped so many simulated mines for targets, we now speak Iranian at meals,” Rinn quipped in one message to Aquilino.

Amid it all, normal training on the

Roberts

went on as usual: fire-and-flooding drills, man-overboard drills, collision drills. Sometimes it seemed like most of the day was spent at general quartersâGQ, the crew called it. Everyone learned to carry their lifejacket and gas mask as they moved about the ship. “GQ was likely to happen every day at all kinds of

hours,” said Chris Pond, the newly arrived hull technician. “Day? Night? You never knew.”

5

It was the same rigorous schedule that Eric Sorensen had helped launch almost two years earlierâwith each new watch, a new exercise.

THE REWARD FOR

the two-week Atlantic voyage was a four-day stop in Palma de Mallorca, a sunny Spanish island town crowded between mountain ridges and attractive beaches.

6

It was the first glimpse of Europe for most of the crew, who swarmed ashore to take in the sights and grab a beer. The cooks restocked the pantry with local goods; bags of bread mix overflowed onto the serving line. Chief Dave Walker departed on an unusual errand: rounding up one of the island's pygmy goats for delivery to the

Jack Williams

, whose skipper had made some sort of crack about the

Roberts

crew “eating goat.”

7

(Walker later denied finding one, which does not explain the photos of a goat aboard ship.)

But the sailors paid for their liberty fun when they ran into a January storm halfway through the Mediterranean. For three days the frigate bulled its way through ten-foot waves that burst over the forecastle and splashed the bridge. The incessant rolling sickened the

Roberts

's young sailors and left even old salts a bit green around the gills. “There were a couple of mornings getting up, where I'd wake up feeling okay, climb down from my third-up rack, and put my feet on the floor,” recalled Joe Baker, the fireman. “The ship would twist, and that would be it. I'd run to the head, puke, and start my day.”

8

At night, Baker and his shipmates tried to wedge themselves into their racks by stuffing boots under the foam mattresses. But the fireman couldn't even trust sleep for solace. One night he dreamed he was looking aft down Main Street, the big passageway between the hangars. He watched the helicopter on the flight deck as the ship tilted back and forth, back and forth. Eventually, the helo fell over the side and disappeared. Then the whole ship turned over. “I remember that dream like it was yesterday,” Baker said. But the fireman's sea legs eventually arrived. “Suddenly, you're walking down a passageway and the ship is forty-five degrees over, and you're just walking, and don't notice,” he said.

9

The squadron ground on through the storm. Fuel was getting low, and they were scheduled for a rendezvous at sea with the oiler USS

Seattle

(AOE 3). The navy relied on underway replenishment, or “unrepping,” the ability to take on fuel without putting into port, to furnish a great tactical advantage over the Soviet navy, which had never quite gotten the knack. Even in fair weather, the maneuver had its risks. The receiving ship approached the larger oiler from behind, slowed to match speeds, and settled into a parallel course. Grunting and yelling, sailors dragged lines and hoses across the hundred-foot gap, all the while keeping a wary eye on the distance between the hulls. The Bernoulli effect created a low-pressure zone in the steel canyon, and ships that drew too close could be sucked into a collision.

Given the thirty-five-knot winds and lashing seas, Dyer wasn't sure unrepping was even possible, but Rinn, to the dismay of his crew, volunteered to give it a shot. There was more than a mite of bravado in the gesture, but there was also a tactical need. The

Roberts

's thirsty gas turbines had burned their way through two-thirds of the ship's fuel, reducing reserves to a level no frigate skipper likes to see. The crew understood the reason for going after the fuel, but the curses that followed the call to refueling stations showed just how little enthusiasm they had for it.

“Everybody was freaking,” Fire Controlman Preston remembered. “âGod, we're gonna die, man, we're going to die,' I remember guys saying. I was back there on a tending line, and it was nastyâraining and cloudy and cold. That big ship wasn't moving much, but we were bouncing all over the place. I remember saying, âOh God, don't let us collide with that thing.' I've seen pictures of what happened when ships collided, and it's not pretty.”

10

Rinn swung his ship around behind the

Seattle

and conned the frigate straight ahead into position off the oiler's starboard side.

11

The crew cursed and held their breath. The sailors got a pilot line across, but could not get the heavy probe to follow.

12

Rinn eventually conceded defeat, but he remained proud that the commodore had allowed him to try.

A few days later the squadron arrived at the far end of the Mediterranean, and the

Roberts

led the squadron through the Suez Canal. Dyer, embarked aboard the

Simpson

, sent Rinn a pat on the back. A signal lamp blinked in Morse code across the blindingly blue water: “You do nice work, Paul.”

13