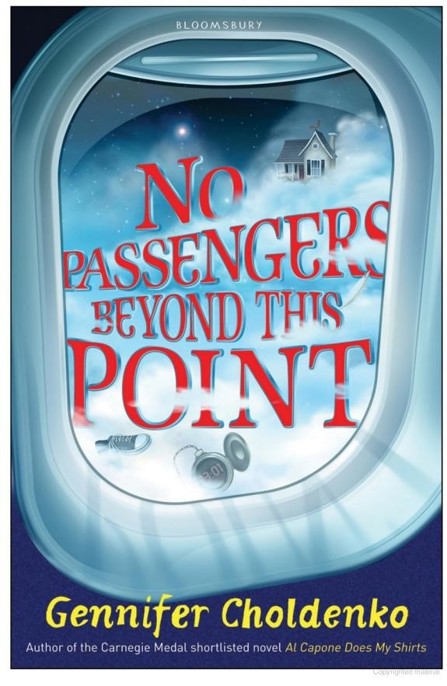

No Passengers Beyond This Point

Read No Passengers Beyond This Point Online

Authors: Gennifer Choldenko

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #General, #Fantasy & Magic

Table of Contents

DIAL BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS

A division of Penguin Young Readers Group

Published by The Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand,

London WC2R 0RL, England

A division of Penguin Young Readers Group

Published by The Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand,

London WC2R 0RL, England

Art copyright © 2011 by Tyson Mangelsdorf

All rights reserved

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Choldenko, Gennifer, date.

No passengers beyond this point / by Gennifer Choldenko.

p. cm.

Summary: With their house in foreclosure, sisters India and Mouse

and brother Finn are sent to stay with an uncle in Colorado until

their mother can join them, but when the plane lands,

the children are welcomed by cheering crowds to a strange place where each of them has a

perfect house and a clock that is ticking down the time.

Choldenko, Gennifer, date.

No passengers beyond this point / by Gennifer Choldenko.

p. cm.

Summary: With their house in foreclosure, sisters India and Mouse

and brother Finn are sent to stay with an uncle in Colorado until

their mother can join them, but when the plane lands,

the children are welcomed by cheering crowds to a strange place where each of them has a

perfect house and a clock that is ticking down the time.

ISBN : 978-1-101-56643-5

[1. Fantasy. 2. Brothers and sisters—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.C446265No 2011

[Fic]—dc22

2009051661

PZ7.C446265No 2011

[Fic]—dc22

2009051661

To Glenys, Grey, Jody, and Herb—

time stood still

in the backseat

on the way

to Red Mountain

time stood still

in the backseat

on the way

to Red Mountain

BLACK CROWS

You have to wait for good things to happen—wait and wait and work so hard—but bad things occur out of the blue, like fire alarms triggered in the dead of night, blaring randomly, a shock of sound, a chatter of current from which there is no turning back.

There’s only the day that starts like any other, and when it ends, it leaves you shaken, wobbly, unsure of where you stand, the patch of ground that holds your feet dissolving, disintegrating from under you. Often there’s a sign, a harbinger of what’s to come. Sometimes there are many signs, like black crows scattered in the road, but they blend into the scenery on the path ahead. You can only spot them when you look back.

CHAPTER 1

A CLOCK STOPS

M

y mom says worry is like a leaky faucet—every drip makes you imagine something bad on the way . . . trouble . . . trouble . . . trouble . . . do something . . . do something . . . do something.

y mom says worry is like a leaky faucet—every drip makes you imagine something bad on the way . . . trouble . . . trouble . . . trouble . . . do something . . . do something . . . do something.

But when you’re twelve and the only guy in the house, you’re responsible for an awful lot. It isn’t just catching mice and taking out the garbage either. You’ve got to be aware.

My sisters don’t worry at all. And my mother? She keeps her concerns to herself. When I ask her what’s wrong she just says nothing . . . nothing . . . nothing.

Still, the evidence is stacking up. The phone rings and my mom dives for it when the caller ID says

Home Fi,

short for Home Finance, which is the people we pay for our house. At dinner there’s mac and cheese and spaghetti and soup—but never chicken, steak, or takeout Chinese. And when it’s team night, there’s no money for pizza. I have to borrow from my six-year-old sister, Mouse, who counts five bucks from the dimes she tapes to the inside of her shoe.

Home Fi,

short for Home Finance, which is the people we pay for our house. At dinner there’s mac and cheese and spaghetti and soup—but never chicken, steak, or takeout Chinese. And when it’s team night, there’s no money for pizza. I have to borrow from my six-year-old sister, Mouse, who counts five bucks from the dimes she tapes to the inside of her shoe.

My older sister, India, has her head in girl world. On a good day, she resembles the crabby cafeteria lady who guards the ketchup with the voice of God. On a bad day . . . let’s not go there.

It’s amazing how little penetrates India’s head. She doesn’t see how jumpy Mom is. She doesn’t notice how Mom spends all her time on her cell under the McFaddens’ big oak tree. Sure, the reception in our house is iffy, but we have a landline . . . why wouldn’t she use that?

Mom’s not limping or coughing or skipping meals. There are no new doctor appointments on the calendar. But nothing else is written down either.

India rolls her eyes when she talks to me about this. “She put the calendar online, Finn, get a grip, you’re like a little old man the way you worry.”

“She hasn’t been using her credit cards either, have you noticed that?”

“We’re broke.” India shrugs. “What’s new about that?”

There’s no telling what Mouse makes of all this. Mouse is like Einstein on a sugar high. If Emily Dickinson and Galileo had a kid, that would be Mouse.

And then there’s Bing, her invisible friend. We’ve told her scientists don’t have invisible friends, but she insists we’re wrong. I don’t know where she gets her information. Do all invisible friends know each other? Is there a clearinghouse for invisible facts? A social network? A chat room? These are the kind of questions you find yourself asking around Mouse.

On the other hand, it makes sense that Mouse’s best friend is imaginary. What other six-year-old thinks the Internet is the secret way zeroes travel at night and the problem with prime numbers is they can’t have babies.

And together, how do Mouse and India get along . . . like two sheets of sandpaper rubbing against each other.

Still, part of me keeps hoping India is right. Maybe we are just broke . . . which isn’t that unusual.

I’m headed for the kitchen to pour myself a bowl of cereal—it’s a little-known fact that guys can’t think without cereal. Only, all that’s left is one lone piece of shredded wheat so stale you could build a bunker with it. I toss the box in the recycling and Mouse pounces on me. She’s holding a picture she made of the backyard with our dog, Henry, and my basketball hoop. All of the refrigerator space down low is taken, so she orders me to put her drawing under the top magnet where my mom keeps PTA forms and permission slips.

That’s when I see how many field trip forms are late. My mom is a teacher. She gets everything back on time.

I track her down walking back from the McFaddens’, cell in hand.

“Mom.” I wave the permission slips in her face.

She nods as if she understands.

My mom has long, straight brown hair like India’s and the same brown eyes as her too—big like in cartoons—only people don’t stare at her the way they stare at India. Coach P. said that’s because India’s “drop-dead gorgeous.”

Not what I want to hear. It would be a lot easier to keep an ugly sister out of trouble, believe me.

Mouse takes after our father’s side of the family. Her hair is a mess of red curls like a football helmet two sizes too large for her tiny freckled face. I resemble both sides: straight brownish reddish hair, lighter skin than my mom’s and India’s, but not freckly like Mouse. I’m short too—we’re all short.

I could grow, though. It could happen. If you’re a short basketball player, you have to be three times better than anybody else. I’m not three times better than everyone else—not even close . . . but I’m working on it.

I’m out there every morning before school doing drills, and I go to practice every afternoon. I help out so I don’t have to pay the league fees. I

make myself useful,

as my mom always suggests. I keep track of the water and the snacks and the drills we do each day. If Coach P. needs help rolling the basketball hoops to the parking lot to create an extra court, I’m the guy.

make myself useful,

as my mom always suggests. I keep track of the water and the snacks and the drills we do each day. If Coach P. needs help rolling the basketball hoops to the parking lot to create an extra court, I’m the guy.

At school I’m the person you borrow an eraser from or call for the homework assignment. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not a teacher’s pet or anything. Kids like me okay. If you’re inviting a bunch of kids, you include me, but if you’re inviting one, I’m never the one. Everybody knows my first name: Finn. No one knows my last name: Tompkins.

We’re inside now and my mom’s scanning the kitchen, her eyes skittering from cupboard to cupboard as if she’s developed a nervous tic. Oh no! What if she has MS? She’s not going to up and die on us like Dad did. Is she?

“What’s the matter?” I ask her.

She holds her breath, then lets the air out in a nervous burst. “Family meeting.”

Family meeting? Why couldn’t she just have said

nothing,

like she usually does?

nothing,

like she usually does?

I try not to hyperventilate as we head for the living room, which is also the den, the dining room, and my mom’s bedroom.

Mouse is skipping and hopping next to Mom. In Mouse World, family meetings are fun.

“India.” My mom raps on the bathroom door.

“Do you mind? I’m peeing,” India snarls.

“No she’s not,” Mouse calls. “She flushed already.”

“Shut up, Mouse!” India shouts, tossing something against the door—the toilet paper roll probably, but a minute later the knob turns and she’s out. The skin around her nose is red and irritated as if it’s been freshly tortured.

Other books

For Everything by Rae Spencer

The Sweetest Love (Sons of Worthington Series) by Higgins, Marie

Craving a Hero: St. John Sibling Series, book 3 by Barbara Raffin

Sea Sick: A Horror Novel by Iain Rob Wright

The Secrets of Silk by Allison Hobbs

Airship Desire by Riley Owens

A Different Game by Sylvia Olsen

Hearts of Smoke and Steam by Andrew P. Mayer

The President's Daughter by Barbara Chase-Riboud

Claiming the Courtesan by Anna Campbell