No Variations (Argentinian Literature Series) (16 page)

Read No Variations (Argentinian Literature Series) Online

Authors: Darren Koolman Luis Chitarroni

In that not too distant past, Henrietta [it’s Bonham-Carter] held the position of [consul] “sympathetic interpreter” (although she couldn’t speak Spanish) for the British Council’s department of cultural exchange. And I had converted one of her nieces into an avid cineaste, for we often went to the cinema together, although I rarely looked at the screen, the object of my gaze being not a projection of light but a girl of flesh and blood, a girl with whom I fell in love not far from where that cinema was located—in Cambridge—while on a picnic beside a stream. But despite the romantic setting, there were no declarations of love, only intimations. Neither were there declarations of independence (I say this because, the previous evening, we had discussed the famous picnic that, according to Auden, inaugurated literature’s independence: the July 4 picnic of 1862 which the Reverend Dodgson and three little girls had in a narrow boat.)

But the evening that concerns us—that of Henrietta’s disapproval—we (Henrietta, Melchior, Nigel, and I) had conversed for quite a long time, and not on academic topics, but about French

chanteurs

[and American

songwriters

], particularly those Henrietta liked best—Brassens and Brel—but also Trenet, Reggiani, and Gainsbourg. [[and Leonard Cohen, [Loudon Wainwright, Harry Chapin, and Gordon Lightfoot]. We stuck with the French ones]] And Tony Gaos, my Argentine friend, also mentioned Polnareff and Dutronc, boasting of his meager knowledge, for which he was forgiven because he was a greenhorn, while I was dueling surreptitiously with the overcooked lamb, trying to forget the taste of the undercooked potatoes, which the wine had barely masked. It was a French cabernet, awful. I expected a lecho de piedra.

I am Spanish. I work, without much passion or conviction, in the publishing industry. I’d like to say our publications are all commercial failures, the kind of literature that must be wary of success, for I certainly have an intuition for such writing—a feel, a nose, if you will—and I’m not bad at the business side of things, and if it weren’t for that pretentious clan of pseudonymous scribblers, here (or I should say “there,” for I’m writing pretty far from where it all happened) we call them “hacks,” and if it weren’t for those tightwad publishers, whose trust [in a noble lineage] helps me to recognize my colleagues under the veil, I can honestly say, and without boasting, that things would be going great.

F. R. Leavis looked like the kind of man he was, or must have been: like a guardian of integrity, a professional who knew how to do his job well, and a man who had a special dedication to his art. Moreover, the old photos I saw of him were a record, despite their weathering, of a man who ensured even his posture should attest to the probity of his criticism, a man whose corrugated features were an index of his candor, of his contempt of ostentation (although there are various anecdotes that give lie to some of these descriptors). Work by Peter Greenham, the varied palette, the tense, nervous brushstrokes: a less rustic-looking Augustus John. The Metropolitan, Urbana. [

Farouche and Uncouth

cancel each other out—the names of those two jokers who made our stay in Stratford-upon-Thames so uncomfortable]. It’s [truly] convenient to be born late and be able to calumniate our precursors and ancestors who rest silent in the grave.

It’s terribly convenient, easy even, or it was back then.

And I recalled an observation of Hugh Kingsmill’s, a man who was always ready to calumniate. He even compiled an anthology of abuses and invectives in which he assured the reader that “invective” is when we do it to them, while “abuse” is when they do it to us. Despite having child-like fingers and a face like a porcelain doll, Ada Antonia (Nonham, according to an Argentine friend) tore apart her bun with as much grace as ferocity, before doling out the same treatment to one of the compositions—seasoned, thanks to her reading, with useless inkhorn terms, vague nonliterary importations, portmanteaus, archaicisms, provincialisms—which I condemned as violating the criterion of those of us who resolved—who were chosen—to dwell on the isle of

understatement

. We

happy few

, of whom there were still a few who were suspicious of immediate happiness. The world is still just an expensive toy we share among us. A large toy, but free, and amusingly adjectival.

I voiced my opinion guardedly, for I knew it was quite possible I was mistaken. But despite trying to appear modest, I was lambasted for the fault; and in being quick with a reply, I was then lambasted for being vain. Commentary between the lines,

footnote for DrScholars

. And not for my sake, but in order to dissuade the others of my opinion, Ada Antonia showed her disapproval in the same idiosyncratic way her sister did. And I was beginning to feel that anything else I said would invite the condemnation of a hypothetical third sister. Of course, I later learned there was indeed a third sister.

But I too had my chance to disapprove. I had objected to Tony’s long tractate on Spenser’s

Mutabilitie Cantos

. It wasn’t just his writing on English poets that irritated me, but his way of speaking the English language—and it wasn’t just me, but quite a few of our friends. But, luckily, none of these were present that night. Take, for example, his odd anachronisms. When he answered the phone, he wouldn’t say

“Hello,”

like normal people, instead he’d say in an affected tone,

“Well

,

are you there?”

His cinematic counterparts were definitely David Niven’s Phileas Fogg and Peter O’ Toole’s Mr. Chips. And if a waiter happened to serve his whiskey neat, he’d ask for a “single rock.”

The story was one of Gerhardie’s tales from

Pretty Creatures

: “The Big Drum.”

Tolstoyan, was how Melchior described it; Chekhovian, insisted Henrietta; at which, my Argentine friend rolled his eyes and sank into his chair with weary exasperation. Seeing that he wasn’t paying attention, I brought the subject of Leavis up again. Malcolm said he doesn’t merit consideration let alone denunciation (Henrietta had already denounced him without the need of words), and that he had the same opinion of Lawrence, at least the Lawrence who wrote

St Mawr

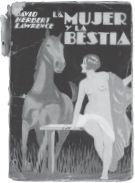

. I recalled my first reading of Lawrence’s

nouvelle

in an edition (I believe it was Argentinian) entitled

La mujer y la bestia

, which I found on my uncle Rafael’s transatlantic bookcase, where it rested alongside works by Joaquín Belda, El caballero Audaz [

The Bolshevik Venus

], Barón Biza, Pitigrilli, and the elusive pornographer, Dionisio Aranciba. I wanted to consult my Argentine friend, but he was in a world of his own. And although an expert on cheap editions of books, I’m not sure if he’d have agreed that in certain cases—translation, for example—Argentine writers are any better or worse than Spanish ones, but I believe in the case of D. H. Lawrence, who for some reason he called “the English Arlt,” his contempt for the writer would’ve only prejudiced his assessment.

Finally we (the survivors of that night—Henrietta, Malcolm, Melchior, and I) discussed

St. Mawr

, although, by that stage, our patience and our level of intoxication had reached saturation point (I suppose I mentioned this already), so that none of us were then innocent of the sins of exaggeration, repetition, superfluity, and digression, and none guilty of the virtues of ingenuity, perspicacity, or insight.

The place in which these events took place, by the way, was Downing College. I mention this because once we finally gave up our ramblings and left, the noise of some students rehearsing a play could still be heard coming from somewhere. But at that hour of night, even Shakespeare would be disagreeable. So, walking down the corridor, all I could hear, all I could think about, were (the bard’s) words, words, words.

Treasons

,

stratagems

,

and spoils

.

But maybe the play was offensive for being crude, as all drama coming out of Oklahoma: a challenge to the audience to forget where we were, where we came from, and even where we’re going, as if a representation—or the cosmetic or zodiacal parody of a representation—could instruct us as to the extent of the will, or better yet, its limits.

We left Downing College, passing through the inconspicuous gateway it shared with a psychiatric clinic. We always enjoyed passing through that gateway at night, moving through the shadows, pretending we were in a spy film.

We (Tony and I) were ambling along casually as the drizzle began to descend, neither of us rushing to get back to our rooms (one of those casual walks we privately relished, during which we avoided all conversation), when we suddenly heard—or, at least,

I

heard—a noise [coming from behind us]: soft plashes, as if our shadows had fallen behind and were playing catch up. I quickly spun around … nothing. Some minutes later, while continuing our walk, I was startled by the recollection of what I believed I saw. It was a face. But the glimpse was so brief, I dismissed it almost immediately. Eventually, I broke the customary silence and said casually to Tony, “I think I saw a face just there … when I turned round … but the features seemed to blend with the backdrop, as if camouflaged … it was like it wasn’t even there.” At which he said, “Really? I just saw the same thing. But it was in front of us.” And it was true. A face with angular features was watching us from the heath; waiting for us; the same face [or countenance] that had followed us at such close distance.

—Allow me to introduce myself: I’m Bertram Fortescue Wynthrope-Smyth, chimney sweep … a quite fortunate fellow really … and in possession of a great fortune too, thanks to all those English chimneys, and the sooty little whelps in one’s employ. And because one is such a busybody, running about the city here and there, one was lucky enough indeed to have caught a part of your conversation. Yes, and one couldn’t ignore the fact you were speaking of something that pertained to the Society of St. Mawr …

Tony looked at me, stupefied: in trying to figure out what exactly was going on, he’d missed part of what this apparition had said. It all seemed like a bad dream, but I knew very well that it wasn’t. And Bertram Fortescue Wynthrope-Smyth seemed to appreciate this.

—As times and fashions have changed—he continued—so have all the [obvious] signs; but the most important ones, the less obvious [hidden] ones, have existed since time immemorial, since before there was any fashion. Nonetheless, when the ephemerals entered one’s consciousness, one tried to behave as if nothing had changed. But one has to admit things are certainly better now that we have words. One is aware you have many questions, but one would rather not answer them. You already know the answers. You may have noticed one speaks English. This is one’s greatest limitation. Indeed, it is the greatest limitation one can possess, but never mind. The reason one came was to extend to you an invitation to a meeting next Friday of the society you so modestly spoke of.

He spoke with that aristocratic accent I despised. “One” this, and “one” that, avoiding at all costs the all too plebeian “I.”

—You must understand it

cum grano salis

—he continued—; if you manage to decipher the words they use, you will be forced to join. But know this: chimneys and books are not so dissimilar; the same skepticism follows from the realization of the bland inconsequence of both ashes and words. There will be no talk of literature, but we should be honored if you choose to accept our invitation.

He gave us a card on which was printed the name of the society and the address where the meeting was to take place. Then he disappeared, leaving us perplexed and almost completely sober.

Until

[Perplexity guaranteed we wouldn’t sleep that night, but not that we wouldn’t be drunk. Tony had a bottle of Tamnavulin in his room. It was standing on his copy of

Old Mortality

. Bertram Fortescue Wynthrope-Smyth had addressed himself as if he were dictating a letter to an esteemed editor (it’s true, we were both editors, but esteemed?) … And Tony was suspicious of this icy character, the chill of his formal diction, his low stature. “Don’t forget, my good friend,” said Tony once the bottle was empty and I was getting ready to leave, “the college and asylum share a gateway.” With no more whiskey to offer, I suppose his generosity prompted a parting platitude.]

[I spent most of the following day in my room. Tony had given me his old TV set. First, I watched an English film that I remembered having seen before on Spanish television. I was surprised on recalling what it was about, and had to conclude it was a sign, a portent: it’s a film about a boy who rides his rocking horse until he almost goes mad, and was inspired by a D. H. Lawrence short story.]