Nocturne (2 page)

“Why do you suppose he shot the cat?” Monroe said.

“Maybe the cat was barking,” Monoghan suggested.

“They got books with cats in them solving murders,” Monroe said.

“They got books with all

kinds

of amateurs in them solving murders,” Monoghan said.

Monroe looked at his watch.

“You got this under control here?” he asked.

“Sure,” Carella said.

“You need any advice or supervision, give us a ring.”

“Meanwhile, keep us informed.”

“In triplicate,” Monoghan said.

There was a double bed in the bedroom, covered with a quilt that looked foreign in origin, and a dresser that definitely was

European, with ornate pulls and painted drawings on the sides and top. The dresser drawers were stacked with underwear and

socks and hose and sweaters and blouses. In the top drawer, there was a painted candy tin with costume jewelry in it.

There was a single closet in the bedroom, stuffed with clothes that must have been stylish a good fifty years ago, but which

now seemed terribly out of date and, in most instances, tattered and frayed. There was a faint whiff of must coming from the

closet. Must and old age. The old age of the clothes, the old age of the woman who’d once worn them. There was an ineffable

sense of sadness in this place.

Silently, they went about their work.

In the living room, there was a floor lamp with a tasseled shade.

There were framed black-and-white photographs of strange people in foreign places.

There was a sofa with ornately carved legs and worn cushions and fading lace antimacassars.

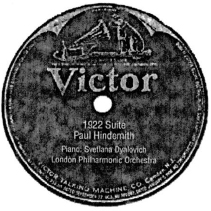

There was a record player. A shellacked 78 rpm record sat on the turntable. Carella bent over to look at the old red RCA Victor

label imprinted with the picture of the dog looking into the horn on an old-fashioned phonograph player. The label read:

Albums of 78s and 33⅓s were stacked on the table beside the record player.

Against one wall, there was an upright piano. The keys were covered with dust. It was apparent that no one had played it for

a long while. When they lifted the lid of the piano bench, they found the scrapbook.

There are questions to be asked about scrapbooks.

Was the book created and maintained by the person who was its subject? Or did a second party assemble it?

There was no clue as to who had laboriously and fastidiously collected and pasted up the various clippings and assorted materials

in the book.

The first entry in the book was a program from Albert Hall in London, where a twenty-three-year-old Russian pianist named

Svetlana Dyalovich made her triumphant debut, playing Tchaikovsky’s B-flat Minor Concerto with Leonard Horne conducting the

London Philharmonic. The assembled reviews from the London

Times

, the

Spectator

and the

Guardian

were ecstatic, alternately calling her a “great musician,” and a “virtuoso,” and praising her “electrical temperament,” her

“capacity for animal excitement” and “her physical genius for tremendous climax of sonority and for lightning speed.”

The reviewer from the

Times

summed it all up with, “The piano, in Miss Dyalovich’s hands, was a second orchestra, nearly as powerful and certainly as

eloquent as the first, and the music was spacious, superb, rich enough in color and feeling, to have satisfied the composer

himself. What is to be recorded here is the wildest welcome a pianist has received in many seasons in London, the appearance

of a new pianistic talent which cannot be ignored or minimized.”

There followed a similarly triumphant concert at New York’s Carnegie Hall six months later, and then three concerts in Europe,

one with the La Scala Orchestra in Milan, another with the Orchestre Symphonique de Paris and a third with the Concertgebouw

Orchestra in Holland. In rapid succession, she gave ten recitals in Sweden, Norway and Denmark, and then went on to play five

more in Switzerland, ending the year with concerts in Vienna, Budapest, Prague, Liège, Anvers, Brussels, and then Paris again.

It was not surprising that in March of the following year, the then twenty-four-year-old musical genius was honored with a

profile in

Time

magazine. The cover photo of her showed a tall blond woman in a black gown, seated at a grand piano, her long, slender fingers

resting on the keys, a confident smile on her face.

They kept turning pages.

Year after year, review after review hailed her extraordinary interpretive gifts. The response was the same everywhere in

the world. Words like “breathtaking talent” and “heaven-storming octaves” and “conquering technique” and “leonine sweep and

power” became commonplace in anything anyone ever wrote about her. It was as if reviewers could not find vocabulary rich enough

to describe this phenomenal woman’s artistry. When she was thirty-four, she married an Austrian impresario named Franz Helder

…

“There it is,” Hawes said. “Mrs. Helder.”

“Yeah.”

… and a year later gave birth to her only child, whom they named Maria, after her husband’s mother. At the age of forty-three,

when Maria was eight, exactly twenty years after a young girl from Russia had taken the town by storm, Svetlana returned to

London to play a commemorative concert at Albert Hall. The critic for the London

Times

, displaying a remarkable lack of British restraint, hailed the performance as “a most fortunate occasion” and went on to

call Svetlana “this wild tornado unleashed from the Steppes.”

There followed a ten-year absence from recital halls—“I am a very poor traveler,” she told journalists. “I am afraid of flying,

and I can’t sleep on trains. And besides, my daughter is becoming a young woman, and she needs more attention from me.” During

this time, she devoted herself exclusively to recording for RCA Victor, where she first put on wax her debut concerto, the

Tchaikovsky B-flat Minor, and next the Brahms D Minor, one of her favorites. She went on to interpret the works of Mozart,

Prokofieff, Schumann, Rachmaninoff, Beethoven, Liszt, always paying strict attention to what the composer intended, an artistic

concern that promoted one admiring critic to write, “These recordings reveal that Svetlana Dyalovich is first and foremost

a consummate musician, scrupulous to the nth degree of the directions of the composer.”

Shortly after her husband’s death, Svetlana returned triumphantly to the concert stage, shunning Carnegie Hall in favor of

the venue of her first success, Albert Hall in London. Tickets to the single comeback performance were sold out in an hour

and a half. Her daughter was eighteen. Svetlana was fifty-three. To thunderous standing ovations, she played the Bach-Busoni

Toccata in C Major, Schumann’s Fantasy in C, Scriabin’s Sonata No. 9 and a Chopin Mazurka, Etude and Ballade. The evening

was a total triumph.

But then …

Silence.

After that concert thirty years ago, there was nothing more in the scrapbook. It was as if this glittering, illustrious artist

had simply vanished from the face of the earth.

Until now.

When a woman the super knew as Mrs. Helder lay dead on the floor of a chilly apartment at half past midnight on the coldest

night this year.

They closed the scrapbook.

The scenario proposed by Monoghan and Monroe sounded like a possible one. Woman goes down to buy herself a bottle of booze.

Burglar comes in the window, thinking the apartment is empty. Most apartments are burglarized during the daytime, when it’s

reasonable to expect the place will be empty. But some “crib” burglars, as they’re called, are either desperate junkies or

beginners, and they’ll go in whenever the mood strikes them, day

or

night, so long as they think they’ll score. Okay, figure the guy sees no lights burning, he jimmies open the window—though

the techs hadn’t found any jimmy marks—goes in, is getting accustomed to the dark and acquainted with the pad when he hears

a key sliding in the keyway and the door opens and all at once the lights come on, and there’s this startled old broad standing

there with a brown paper bag in one hand and a pocketbook in the other. He panics. Shoots her before she can scream. Shoots

the cat for good measure. Man down the hall hears the shots, starts yelling. Super runs up, calls the police. By then, the

burglar’s out the window and long gone.

“You gonna want this handbag?” one of the techs asked.

Carella turned from where he and Hawes were going through the small desk in the living room.

“Cause we’re done with it,” the tech said.

“Any prints?”

“Just teeny ones. Must be the vic’s.”

“What was in it?”

“Nothing. It’s empty.”

“Empty?”

“Perp must’ve dumped the contents on the floor, grabbed whatever was in it.”

Carella thought this over for a moment.

“Shot her first, do you mean? And then emptied the bag and scooped up whatever was in it?”

“Well … yeah,” the tech said.

This sounded ridiculous even to him.

“Why didn’t he just run off with the bag itself?”

“Listen, they do funny things.”

“Yeah,” Carella said.

He was wondering if there’d been money in that bag when the lady went downstairs to buy her booze.

“Let me see it,” he said.

The tech handed him the bag. Carella peered into it, and then turned it upside down. Nothing fell out of it. He peered into

it again. Nothing.

“Steve?”

Cotton Hawes, calling from the desk.

“A wallet,” he said, holding it up.

In the wallet, there was a Visa card with a photo ID of the woman called Svetlana Helder in its left-hand corner.

There was also a hundred dollars in tens, fives and singles.

Carella wondered if she had a charge account at the local liquor store.

They were coming out into the hallway when a woman standing just outside the apartment down the hall said, “Excuse me?”

Hawes looked her over.

Twenty-seven, twenty-eight, he figured, slender dark-haired woman with somewhat exotic features spelling Middle Eastern or

at least Mediterranean. Very dark brown eyes. No makeup, no nail polish. She was clutching a woolen shawl around her. Bathrobe

under it. Red plaid, lambskin-lined bedroom slippers on her feet. It was slightly warmer here in the hallway than it was outside

in the street. But only slightly. Most buildings in this city, the heat went off around midnight. It was now a quarter to

one.

“Are you the detectives?” she asked.

“Yes,” Carella said.

“I’m her neighbor,” the woman said.

They waited.

“Karen Todd,” she said.

“Detective Carella. My partner, Detective Hawes. How do you do?”

Neither of the detectives offered his hand. Not because they were male chauvinists, but only because cops rarely shook hands

with so-called civilians. Same way cops didn’t carry umbrellas. See a guy with his hands in his pockets, standing on a street

corner in the pouring rain, six to five he was an undercover cop.

“I was out,” Karen said. “The super told me somebody killed her.”

“Yes, that’s right,” Carella said, and watched her eyes. Nothing flickered there. She nodded almost imperceptibly.

“Why would anyone want to hurt her?” she said. “Such a gentle soul.”

“How well did you know her?” Hawes asked.

“Just to talk to. She used to be a famous piano player, did you know that? Svetlana Dyalovich. That was the name she played

under.”

Piano player, Hawes thought. A superb artist who had made the cover of

Time

magazine. A piano player.

“Her hands all gnarled,” Karen said, and shook her head.

The detectives looked at her.

“The arthritis. She told me she was in constant pain. Have you noticed how you can never open bottles that have pain relievers

in them? That’s because America is full of loonies who are trying to hurt people. Who would want to hurt

her?

” she asked again, shaking her head. “She was in so much pain already. The arthritis.

Osteo

arthritis, in fact, is what her doctor called it. I went with her once. To her doctor. He told me he was switching her to

Voltaren because the Naprosyn wasn’t working anymore. He kept increasing the doses, it was really so sad.”

“How long did you know her?” Carella asked.

Another way of asking How

well

did you know her? He didn’t for a moment believe Karen Todd had anything at all to do with the murder of the old woman next

door, but his mama once told him everyone’s a suspect till his story checks out. Or

her

story. Although the world’s politically correct morons would have it “Everyone’s a suspect until

their

story checks out.” Which was worse than tampering with the jars and bottles on supermarket shelves—and ungrammatical besides.

“I met her when I moved in,” Karen said.

“When was that?”

“A year ago October. The fifteenth, in fact.”

Birthdate of great men, Hawes thought, but did not say.

“I’ve been here more than a year now. Fourteen months, in fact. She brought me a housewarming gift. A loaf of bread and a

box of salt. That’s supposed to bring good luck. She was from Russia, you know. They used to have the old traditions over

there. We don’t have any traditions anymore in America.”