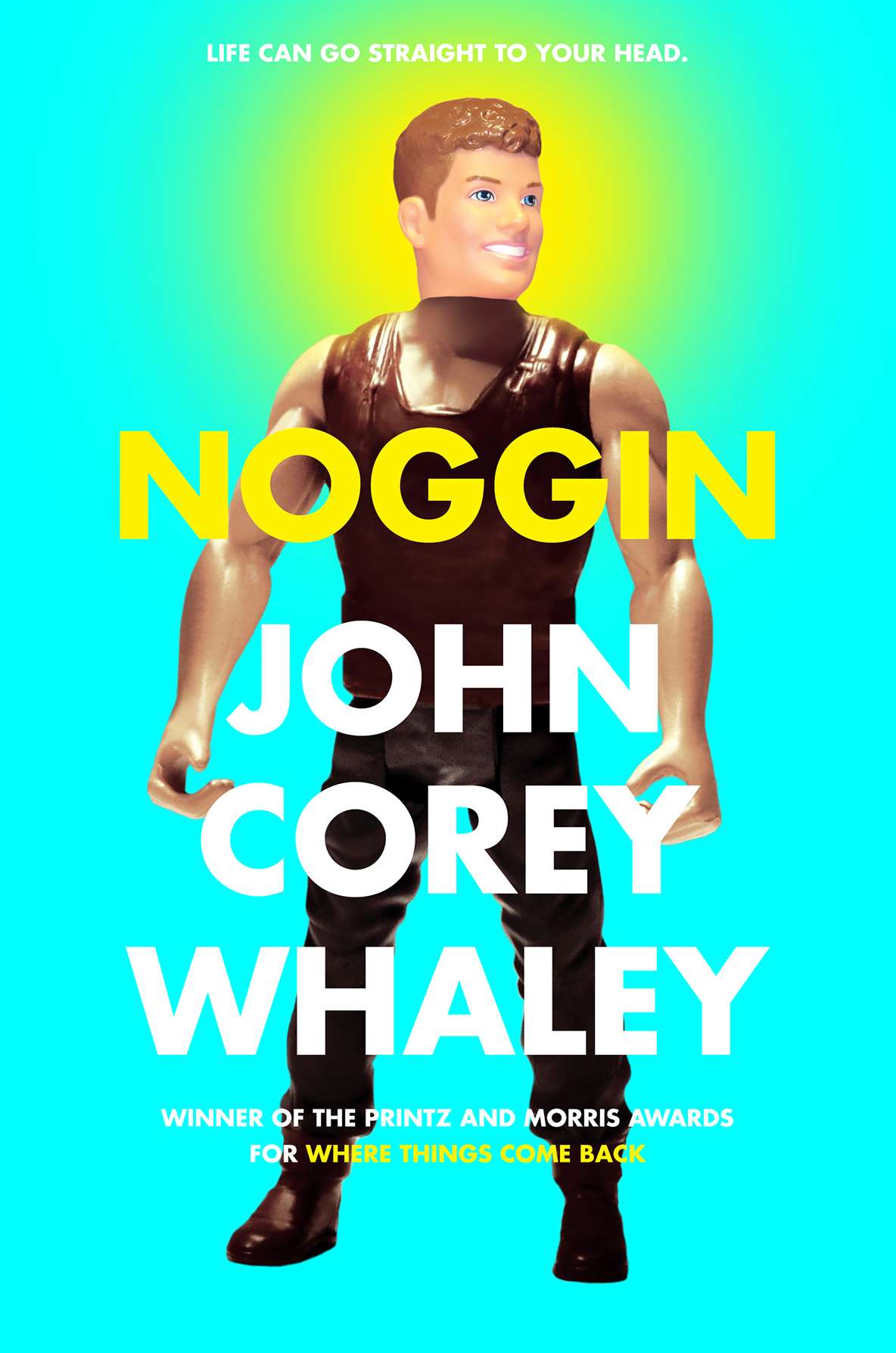

Noggin

Authors: John Corey Whaley

Thank you for downloading this eBook.

Find out about free book giveaways, exclusive content, and amazing sweepstakes! Plus get updates on your favorite books, authors, and more when you join the Simon & Schuster Teen mailing list.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com/teen

FOR MOM AND DAD, WHO ALWAYS HELP ME KEEP MY HEAD ON STRAIGHT.

“It is just an illusion here on Earth that one moment follows another one, like beads on a string, and that once a moment is gone, it is gone forever.”

—Kurt Vonnegut Jr.,

Slaughterhouse-Five

ADVANCED STUDIES IN CRANIAL REANIMATION

Listen—I was alive once and then I wasn’t. Simple as that. Now I’m alive again. The in-between part is still a little fuzzy, but I can tell you that, at some point or another, my head got chopped off and shoved into a freezer in Denver, Colorado.

You might have done it too. The dying part, I mean. Or the choosing-to-die part, anyway. They say we’re the only species on the planet with the knowledge of our own impending doom. It’s just that some of us feel that doom a lot sooner than expected. Trust me when I tell you that everything can go from fine and dandy to dark and depressing faster than you can say “acute lymphoblastic leukemia.”

The old me got so sick so fast that no one really had time to do anything but talk about how sick he got and how fast he got that way. And the chemo and the

radiation and the bone marrow transplants didn’t do anything but make him sicker faster and with much more ferocity than before.

They say you can’t die more than once. I would strongly disagree. But this isn’t a story about the old me dying. No one wants to hear about how I told my parents, my best friend, Kyle, and my girlfriend, Cate, that I was choosing to give up. That’s a story I don’t want to tell. What I do want to tell you, though, is a story about how I suddenly found myself waking up in a hospital room with my throat sore, dry and burning, like someone had shoved an entire bag of vinegar-soaked cotton balls down it. I want to tell you about how I was moving my fingers and wiggling my toes and how the doctors and nurses standing around me were so impressed with this. I’m not sure why blinking my eyes earned a round of applause and why it mattered that I was peeing into a bag, but to these people, it was like they were witnessing a true miracle. Some of the nurses were even crying.

I want to tell you a story about how you can suddenly wake up to find yourself living a life you were never supposed to live. It could happen to you, just like it happened to me, and you could try to get back the life you think you deserve to be living. Just like I did.

They told me I couldn’t talk, said it was too early to try that just yet. I didn’t know why, but I listened anyway. My mom and dad walked in, and she cried big tears and he went in to touch my face, and the nurse asked him to

wait, asked him to please step aside until they were sure everything was working okay.

They gave me a small white board and a marker and told me to write my name. I did. Travis Ray Coates. They asked me to write down where I live. I did. Kansas City, Missouri. They asked me to write down my school. I did. Springside High. They asked me to write down the year. I did. Then the room got suddenly quiet, and even though it was bright and clean and I could smell medicine and bleach, I knew something was wrong.

This is when they told me that they’d done it. They’d gone through with the whole cranial hibernation and reanimation thing. They’d actually gone and cut my head off. I was so sure they’d put me under and changed their minds and that I’d gone through all that paperwork for nothing. But then my mom held up a mirror, and I saw that my head was shaved nearly bald and that my neck had bandages wrapped all around it. I looked pretty rough—my lips were purple and cracked, my cheeks were flushed, and my eyes were big and glazed over. Drugged, my eyes were drugged.

I’m going to tell you the truth here and say that I never, not once, not even for a tiny second, thought this crazy shit would work. And I never thought they did either. My parents, I mean. But I looked up at their wet eyes and felt their hands on my hands, and I knew right then that they were as happy as any two people had ever been. Their dead son lying on a bed in front of them, silent but with

a beat in his chest again. Mary Shelley’s nightmare come true, right there in a hospital in Denver.

Hospitals. I knew hospitals. I knew them like most kids know their own homes, know their neighborhoods, and know which yards to avoid and which ones it’s safe to leave your bike in. I knew a nurse was only allowed to give you extra pain meds if a doctor had signed off on it first but that getting extra Jell-O only took a few smiles and maybe a joke or two, maybe a flash of the dimples. And like a factory, a hospital has its own rhythm, sounds from every room that collide in the air and echo down into your ears and repeat themselves, even in the nighttime, when the world wants so bad to appear silent and quiet and peaceful. Beeps, footsteps, the tearing of plastic, spinning wheels on carts,

Wheel of Fortune

on the neighbor’s TV. These were the sounds I died to, and these were the ones that welcomed me back. A world so noisy you have to lean up a bit to hear the familiar doctor as he tries to speak over it all, and just as you were starting to get used to the light, you have to close your eyes to hear him. A world that looks almost exactly the same as the one you closed your eyes to before, so much the same that you think about laughing because you got so close to being done with it all. Until you finally hear the doctor as he speaks a little louder this time.

“Welcome back, Travis Coates.”

WELCOME BACK, TRAVIS COATES

When Dr. Lloyd Saranson from the Saranson Center for Life Preservation showed up at my house, I was puking in the guest bathroom with my dad sitting on the edge of the tub and patting my back. By that point I’d been sick for almost a year, seen every cancer specialist in the tri-state area, and given up all hope of survival.

Then this guy walks in and insists on pulling me out of my deathbed long enough to pitch us the craziest shit in history. And we listened because that’s what desperate people do. They listen to anything you have to say to them.

“Travis,” he said. “I want to save your life.”

“Back of the line, buddy. No cutting.” I looked to my parents with a grin, but they were either too tired or too sad to laugh.

“And how do you plan to do this?” Dad asked.

“Are you familiar with cryogenics?” Dr. Saranson asked with a serious tone.

“All right. Thanks for stopping by,” Mom said, standing up and signaling for the door.

“Mrs. Coates, I wish you’d just hear me out for a few minutes. Please.”

“Doctor, we’ve really been through a lot and—”

“Mom,” I interrupted her. “Please don’t take this away from me.”

“Fine, go on,” she said, sitting back down.

“Travis,” he said. “Your body is done on this earth. We all know that. It’s a sad state of affairs, but there’s just no way we can change that.”

“Try harder, doc. You’re losing us here,” I said.

“Right. That’s to say, with what I’m proposing to you, that all doesn’t matter anymore.”

“Why’s that?” I asked, looking to my parents, who were on the verge of launching from their seats and attacking him.

“Well, because in the future there’ll be different ways for you to . . . exist.”

“The future,” I said. This wasn’t something I’d given too much thought lately.

“Exactly. The future. Imagine, Travis, that you could simply fall asleep in this life and wake up in a new one someday.”

“How far into the future?” I asked. In my mind I was

seeing my spaceship folding down into a suitcase like George Jetson’s.

“With our latest breakthroughs we’re hoping to develop the means to reanimate our first patients within a decade or two.”

“You’re serious, aren’t you?” Dad asked.

“Quite serious, Mr. Coates.”

“Has anyone else volunteered for this?” I asked.

“You’d be our seventeenth patient.”

“So cryogenics,” Dad said. “You want to freeze Travis with the hope of bringing him back someday?”

“Not exactly,” he said. “As I was saying, Travis’s body is done on this earth.”

“Oh my God,” Mom said quietly, this look of terror and disgust washing over her face.

“My head?” I pointed to it when I spoke, like the surgeon needed that. “You want to freeze

just

my

head

?”

“It’s the only part of you not riddled with cancer cells.”

This guy, he talked like he’d been there with us the whole time—with this familiarity and casualness that most strangers never used around “the dying kid.” I liked it a lot, actually.

“So you knock me out and freeze my head, and I’m supposed to wake up in the future without a body and just roll with it?”

“Actually, there are several options for your hypothetical future recovery scenario, should we proceed any further.”

Options for My Hypothetical Future Recovery Scenario (Abridged)

1) Full-body regeneration through stem cell implantation into controlled fluid environment

2) Transplantation of full cranial structure onto robotic apparatus

3) Transplantation of full cranial structure onto donor body

4) Neuro-uploading into donor body and brain

Personal Reactions to Options for My Hypothetical Future Recovery Scenario (Abridged)

1) Gross

2) ROBOT ARMS!!!

3) Well, that’s not happening

4) Say whaaaat?

After Dr. Saranson left that day, Mom and Dad started laughing, which would’ve been really nice for a change had I not secretly decided that I was going to volunteer whether they liked it or not. I was tired of dying, and I figured since this was the best idea I’d heard in months, and didn’t involve radiation or weeks of vomiting, then I may as well go for it. I saw it like this: I was going to die either way. Why shouldn’t I be able to just fall asleep

with this slight (okay—completely impossible but still slight) possibility of my return instead of continuing on this never-ending torture fest of having everyone I love watch me slowly fade away? Maybe I’d never really get to come back, but damn it, once that idea got into my skull, there was no letting it go.

My parents took a little less convincing than I’d thought. They loved me. I was dying. This was a way for me to not be dying anymore. It was weird how simple it all became once the decision was made. I never thought knowing my actual expiration date would make a difference, but it did. It made a difference to us all. The few people who got to know we were doing it had a hard time understanding why, but in the end I think maybe they all needed the relief of letting go just as much as I did. So I let go. We let go. And then I came back. Holy shit, I came back.

• • •

It was good being back for just about as long as it took for my parents and Dr. Saranson to explain that I was attached to someone else’s body. Then they had to go ahead and sedate me again because I kept clawing at my neck and ripping out my IV. The next time I woke up, my wrists and ankles had been restrained with cushiony little straps, and the looks on my parents’ faces had worn a bit, like they’d forgotten how to sleep. These looks were much closer to the way I’d remembered them.