North Yorkshire Folk Tales

Read North Yorkshire Folk Tales Online

Authors: Ingrid Barton

ONTENTS

1

People

2

Giants

3

Dragons

7

Witches

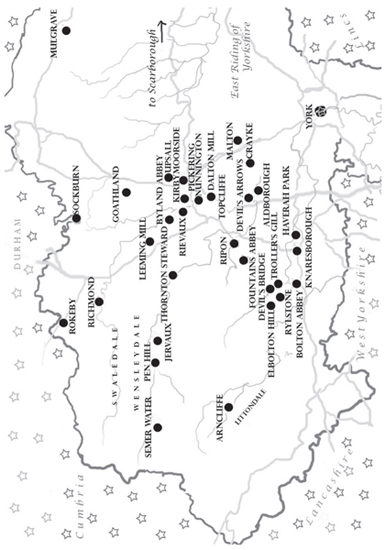

TORY

L

OCATIONS

NTRODUCTION

What are folk tales? Tales told by working people and recorded by those with enough leisure, education and income to go around collecting them. The concept of ‘folktale’ is relatively recent. Before that, there were just stories that lived or died on the tongues of local people. It was only when they began to disappear that they suddenly became precious enough to be given a name.

In Yorkshire, as in the rest of England, there is no longer a direct line of oral storytelling tradition as there still is in Iran, Morocco or the traveller communities of Scotland. We still pass on jokes or urban myths – the buds of new folk tales – but to tell stories and develop them requires time, and time is singularly lacking in our age. The poorest agricultural worker of the past spent more time chatting to his friends and family than most of us do now (if you exclude the barrier method of the Internet).

We can no longer rely on the oral tradition, but fortunately, in Yorkshire at least, we can get some idea of the richness of that lost heritage from the work of a few men (and a couple of women) who were sufficiently interested in the common people around them to record their tales with some sympathy. They were no Brothers Grimm: collecting stories was an interest rather than a passion, however, they realised just in time that reforming clerics and the growth of schools and literacy would eventually lead to the disappearance of folk tales just as they were leading to the suppression of folk customs.

It is inevitable then that most of the stories in this book have been collected by people, mostly vicars, who were not themselves storytellers; and some bear the heavy hand of Victorian ‘improvement’. I have treated them in the way any modern oral storyteller does by taking the often sketchy outline of the stories and making them my own by adding colour and details. Some people may object to my occasional use of Yorkshire dialect phrases, but Yorkshire dialect was the pithy, muscular form of speech in which the stories would originally have been told; to leave it out altogether would be to insult those old tellers. (On the other hand, if you are an expert in Yorkshire dialect I apologise for any mistakes.)

Some people do not consider historical stories, or ones about historical people, to be folk tales; I have only included ones that have a genuine folk element (i.e. they are what folk wanted to believe was true; so Archbishop Lancelot Blackburne becomes a pirate and the squalid Dick Turpin a hero).

North Yorkshire is a very large area and it has many stories, some of which are very similar (

See

Dragons). I have tried to give a broad range of the most lively ones, but there are plenty more. Folk tales are still growing out there, though slowly nowadays, rather like yew trees.

Sources for further reading can be found at the back of the book, along with notes for most of the stories.

Ingrid Barton, 2014

P

EOPLE

S

OMETHING

TO

H

IS

A

DVANTAGE

Hambledon Hills

There was once a man living at Upsall in the Hambledon Hills who had a dream. In it he heard a voice saying, ‘If you stand on London Bridge you will hear something to your advantage.’

The man was as poor as a church mouse so he had nothing to lose. He was also a Yorkshireman and knew better than to blab to anyone, so one day, without telling his friends or neighbours, he locked the door of his little cottage and with half a loaf of bread in his pocket, set off for London.

It was a long way so he hitched rides on passing carts, and sometimes stopped off for a day or two carrying out odd jobs to pay for his next few nights’ board and lodging, but slowly he got nearer to the capital. At last he fell in with some drovers who were driving cattle to the London markets and they took him right into the city. He did not tell them about his dream and they thought him just another amiable idiot going to gawp at the sights.

For a while he did indeed enjoy walking by the mighty River Thames, impressed by the size and wealth of the buildings and the splendour of the clothes and carriages of the gentry. Then he thought, ‘If I was to hear something to my advantage I could be living as high as these folk! Now where is that bridge?’ Guessing that if he kept along the river he would eventually get to it, he hurried on.

His first sight of the famous London Bridge was inspiring, for this was in the days when there was only one bridge across the river and it was always crowded. There were people and horses and wagons and cattle, and even a flock of geese with tarred feet trying to cross the bridge. Those coming from the south were supposed to keep to the left, and those going out of the city to the right, but not everyone obeyed the rules and every so often a struggle would break out. There were shops and houses too, old ones, built right onto the bridge itself, leaning out over the river on both sides, so that our man was actually on it before he had realised.

‘I mun be a reet gormless gavrison to have come here in first place,’ said our man. ‘But now I’m here I mun mak the best on it.’ He pushed and shoved his way along, among all the other pushers and shovers until he had crossed the whole bridge. ‘Now what?’ he wondered, for though he had kept an ear out hoping to hear ‘something to his advantage’, he had learned nothing except some interesting new southern swearwords.

He turned back and once more crossed the bridge, but once again nothing out of the usual happened. He was losing hope now and cursed himself for an idiot as he thought of the long road home. ‘Still, third time pays for all!’ he thought and set off again. This time he stopped in the middle, where there was a narrow gap between one house and another. He leaned on the parapet looking out over the river.

‘A fine prospect!’ said a voice at his elbow. A respectable, though not richly dressed, young man stood there. ‘Might I join you?’

‘I suppose,’ said our man suspiciously. He had heard many tales of the tricksy nature of Londoners and how they cheated poor Yorkshiremen out of their money. ‘I’ve got no brass, tha knows,’ he added bluntly.

The young man laughed, ‘I assure you I have no designs on your pocket. We’re not all thieves here! I can tell that you’re a Yorkshireman, by your talk. I spent many years in York as a boy. It’s a pleasure to hear the old accent again.’

‘Oh aye.’

‘Yes indeed. Fine horses, fine ale and fine lasses there. I remember it well.’

Our man was a little mollified to hear his county praised, so he moved over to let the young man lean beside him. They looked out over the river in silence for a bit, enjoying the sight of so many boats, little and big, crowding the waterway.

Finally, the young man said, ‘They’re talking of knocking all these old shops down and building a new bridge. It’d be a shame, don’t you think?’

‘Mebbe.’

‘So what has brought you down to this den of iniquity from God’s own county?’

Our man hesitated. ‘I – well, I dreamed I should.’

‘And you followed your dream. Oh my dear fellow, do you realise how fortunate you are! How I envy you!’ the young man sighed, thinking of the dreary counting house where he worked and from which he dreamed of escaping. ‘How I wish I might follow your example!’

‘You have dreams, then?’

‘Don’t all men dream that life might be better?’

‘An’ do their dreams come true?’

‘True? Alas, no. What joy to have one’s dreams come true!’

‘I reckon all that about dreams coming true is just shite,’ said our man gloomily.

‘Oh, don’t say that!’ spluttered his companion. ‘The world would be such a terrible place if we didn’t have dreams, don’t you think?’

‘Have you ever dreamed and it come true, then?’ our man pressed on.

The young man hesitated. ‘Oh, you mean dreams in your sleep? No – though, now you mention it, curiously enough I had one the other night that I hope might do so.’

‘Did you now!’

‘Yes, I dreamed I found a treasure!’

Our man turned and fixed him with a piercing eye.

‘Oh aye?’

‘I dreamed that I was in an old castle courtyard, and there was a big elder tree there.’

‘That’s nowt special.’

‘Wait! When I dug beneath it I unearthed a huge pot of gold!’

‘Now that’s more like!’ breathed our man. ‘Pity you don’t know where it was!’

‘Ah, but I do – well, I remember the name, but unfortunately I’ve not the slightest idea where it is.’ The young man sighed sadly.

‘What was the name? Happen I might know it.’

‘Up – something. Oh, I know; Upsall. You ever heard of it?’

‘No.’

![]()

Back in Upsall his friends teased him about his prolonged absence.

‘He’ll have a fancy woman down there!’ said one.

‘No, more like he’s being chased by some lass he’s fathered a bairn on!’ said another.

‘No, no. He’s been away in Pudding Pie Hill – wi’ the fairies!’ said a third.

Our man sat quietly and smiled. He could take jokes; he knew that they would soon be laughing on the other side of their faces.

That night he left his cottage just as if he was going for a walk – if you ignored the spade over his shoulder. The old castle of the Scropes had been abandoned since the Civil War and its gates had rotted away long ago. He peered into the courtyard with its roofless stables and piles of rubbish. Ivy was claiming the place, shooting up the keep walls and concealing in many humps and bumps the fallen stonework. It was very dark and our man had heard tales of ghosts. He clutched his spade and thought of the golden treasure.