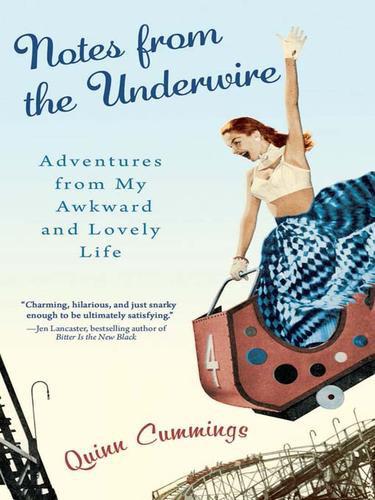

Notes From the Underwire: Adventures From My Awkward and Lovely Life

Read Notes From the Underwire: Adventures From My Awkward and Lovely Life Online

Authors: Quinn Cummings

Tags: #Humor, #Women, #Personal Memoirs, #Biography & Autobiography, #Essays, #Form, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

Adventures from My Awkward and Lovely Life

To Consort, for getting on the plane

THIS WASN’T IN MY PLANS FOR THE DAY

.

Alice and I attended a parent-and-child art class. While Alice mused over a composition that would be listed in future catalogs of her work as

Meditations on Pink Tissue

,

Elmer’s Glue, and Glitter

,

#186,

I had taken a moment to run to the bathroom. Racing back so I could be the restraining force between Alice and a Big Gulp–sized container of glitter, I dashed up the stairs and bounded through the doorway into the classroom. Only, to keep things lively, I didn’t pass through the open door but slammed into its adjacent plate-glass window instead. The flat light shining through from the classroom had rendered it invisible. Now it was abundantly visible thanks to the smeary marks made by my nose, lips, and cheek crashing into its surface at full trot.

This won’t come as a shock to anyone who knows me. I started walking at nine months. I started walking into things at nine months and one hour. My everyday walk resembles the frantic dart of a small, excitable lizard, and I seem to be unable to grasp the notion that inanimate objects don’t know how to get out of my way. Smashing into a window was a new trick altogether. I had mutated from lizard to sparrow.

The door opened—the real door, not the portal of shame—and several parents and the art instructor looked at me with concern. The sound of my face slamming against the thick glass

must have been somewhat alarming. One of the parents, a casually well-dressed dad in his forties, came to where I was sitting on the linoleum and asked, “Are you all right?”

I thought about this question. Noses were not designed to absorb the impact from a head-to-wall collision at any speed above a crawl so the odds of my being fully all right weren’t good. I thought about this for some time. Perhaps too much time. I wondered if I had a concussion. Surreptitiously, I held out two fingers and counted them. This cheered me up until I realized someone else was supposed to run that test. If I’m holding up two fingers there’s a pretty high likelihood I’ll know I’m holding up two fingers. Unless, of course, the concussion is affecting my memory, in which case I might be able to recognize two fingers but wonder whose nail-nibbled fingers they are, which would be another problem. Since the recollection of smooshing my face into plate glass was excruciatingly vivid, I had every reason to suspect my memory was unaffected. None of these thoughts helped answer the immediate question regarding my health, however, so I went with the always classic, “Yes, I’m fine.”

As the concerned father stared deeply into my eyes, I worried for a moment that he found idiots who think they can pass through solid objects desirable and was about to hit on me. Then I noticed his gaze had a certain professional quality.

“Are you a doctor?” I asked, discreetly dabbing under my eyes to see if my brain was leaking out.

“I was a cardiac surgeon. Now I run a medical-research hedge fund.”

Ladies and gentlemen, may I present the most intimidating father in this area code, talking to the woman who had just seen fit to emulate a windshield gnat. I dabbed. I smiled. I assured

everyone that I was fine. Really. Fine! Eventually, we all returned to our art making.

Dr. Hedge-Fund and his son went back to creating Michelangelo’s

David

out of cotton balls and paste while they parried some sort of word game in Mandarin. I slid into the seat next to Alice where her work surface, her lap, and her hair led me to understand she had moved into the glitter phase of her creation without my counsel. She looked up. “Weren’t you going to the bathroom?” When a small girl is struck by glitter-lust, her mother can leave the room, fling herself loudly against a solid object, and rest easy in the knowledge she wasn’t missed.

I spent the better part of that night in front of the bathroom mirror poking at my nose, flinching, and poking it some more. Under the best of circumstances I am no great fan of my nose. For one thing, its bridge is too flat. For another, it’s too short, and the combination of wide and short means my nose looks square, an adjective never associated with the great beauties of any era. It’s a tolerable nose in person but it never photographs well. From certain angles it looks like I have a potato taped to my face. After the window incident, I appeared to have sprung a butcher-block workbench between my eyes. I was starting to miss the familiar square.

To add further insult to my injury, my nose was no longer drawing in the usual amounts of air. My left nostril had closed up shop and taken to its bed. I wanted to whine and I needed to find someone obligated to feign interest in all this. So, of course, I buttonholed Consort.

“Why did every self-defense course I’ve ever taken tell me how easy it is to break a person’s nose?” I asked him.

Consort stared at me expectantly. I sighed, and a few moments passed.

He said, “That was rhetorical, right?”

“It seems so unfair,” I continued, ignoring his question. “I was always told the nose breaks easily. I should be in pre-op for a nose job right now.”

He stared at me in wonder and confusion. “I’m sorry, am I hearing you say you want a nose job?”

“Of course, I want a nose job. I hate my nose. It should be cuter. Or it should at least deliver oxygen to my brain. A nose job might accomplish one of those requirements.”

“Then…” he said softly, tiptoeing through the minefield that is my belief system, “you should get a nose job…”

“You silly. I can’t do that,” I said patiently. “That would be cheating.”

I will explain. When you live in Los Angeles your entire life, it’s drummed into you how nothing is permanent. Don’t like your name? Change it. “Tawnee” is nice, and isn’t in high rotation this season. Breasts can expand and contract with the style of the moment. A chin-length bob can become tumbling locks in an afternoon and pixie-short by nightfall. The official motto of Los Angeles is “Semper Pulcher et Connubialis.” Loosely translated, this means: “You are entitled by sheer virtue of being born to remain ever young and sexually desirable. You also get to possess any object that delights you.”

Since every person in Los Angeles with a working credit card and a phone is currently interviewing plastic surgeons to redo their liposuction or freshen up their labia, I must—as the most contrary person in the world—get

nothing

changed. I must live with the nonphotogenic, nonfunctional nose I was given because living with the nose I was given at birth is making a point, even if I no longer recall what that point is.

My attitude might have had something to do with being honest. Or seeking a stoic calm. Or not wanting a nose that screams “Dr. Feingold’s Spring 2008 collection.” Still, as I explained to Consort, even the best laws have loopholes. I can get a face-lift when I’m older because a face-lift wouldn’t actually change anything, it would just restore me to a previous condition—a condition I might have kept had I been more vigilant about sunblock, eaten nothing but cruciferous vegetables, and lived in a gravity-free environment. A face-lift isn’t cheating; it doesn’t change what I was given by nature. A face-lift is just a horrendously expensive do-over, with Vicodin.

Consort, as he often does after I explain how things work, attempted to present a neutral expression. But he just looked alarmed.

The next morning, my nose was blue. Not navy blue, more of an aquamarine. Certainly nothing I couldn’t hide with a little makeup, but since touching my nose sent waves of pain down to my floating ribs, I was just going to have to dress around it. For entertainment value, I called my ear-nose-and-throat doctor. It was before 9:00 a.m. so his service asked if I wanted to leave a message.

“Yeah, just let him know that I ran into a plate-glass window yesterday and my nose didn’t bleed or anything but now it’s sort of aquamarine-blue and I can’t breathe through one nostril, and also, I don’t want to sound shallow, but I’m a little asymmetrical, I mean, we’re all asymmetrical, right, but this is…”

“Please hold.”

I assumed she had another call. I tried humming along to the hold music, but humming made my nose vibrate unpleasantly so I stopped. Within a minute, I heard my doctor’s voice.

“Quinn,” he said jovially. “What did you do now?”

I will never use my ENT doctor as a character witness; he knows too much. He always sees me at my worst, which frequently involves Q-tips and an eardrum. At least this was a new injury. I suspect he likes me in the same way police officers maintain an amicable rapport with certain neighborhood criminals. Everyone has their job, nothing personal. Three or four times a year I put my health at risk. Three or four times a year he comes along and saves me from myself, always taking care to laugh at my misadventures in the least derisive way possible. He’d see me that afternoon.

I took my Easter egg–tinted nose to Beverly Hills, where all doctors in Los Angeles practice. To outsiders, Beverly Hills is where celebrities congregate on corners, comparing Bentleys. In reality, Beverly Hills is where celebrities wear paper kimonos, read last month’s

Good Housekeeping

, and urinate in a cup. The nurse called my name and pointed down the hallway. “You’re in room seven,” she said.

This was only slightly helpful as none of the doors displayed any sort of number. I drifted toward the first room and the nurse called out, “Not six. Seven!” in a tone that indicated even coliform bacteria knew how to find room seven. Stung, I spun around and followed her finger toward the next door, moving quickly to get away from her judgment and my disgrace. As it turns out, this was room five. Rooms seven and five were identical except the door into room seven was open and the door into room five was closed. I had run into another closed door.

It’s not that I never learn. I learn things all the time. The lesson I’m learning now is that learning things doesn’t change my behavior. When I was sixteen, I started saying “I don’t actually like acting…” but it took another eight years for me to

finish the sentence, “and I’m not going to do it anymore.” Since I was eleven I’ve known I can’t wear yellow, but every three years I convince myself “butter” or “lemon drop” isn’t really yellow and I wear it until a close friend inquires if I might be experiencing liver failure. By the time I was twenty-four, I was already exquisitely aware that nothing good ever happened after the phrase, “Yes, let’s get another pitcher of margaritas,” but I continued that behavior for years. It’s like one part of my brain takes notes and learns but the rest of my brain shouts “LA LA LA. Can’t possibly hear you over this questionable activity.” I sometimes wonder if my last words on this earth will be something like, “Oh, I

knew

this wouldn’t work.”

I was sitting on the floor in front of the examining room. The nurse who had been directing me into room seven raced over to me, saying, “Oh my God, are you okay?” which would have sounded better had she not been giggling and I not flat on my ass on the linoleum. I dabbed at my nose with a professional air and said briskly, “Just getting my money’s worth out of today’s visit.” I stood up, looked around carefully, and determined the only other room with an open door must be room seven. I had every intention of walking in a steady and measured pace into the room. Instead, I darted across the hallway, hit my elbow on the counter, and flung myself into the chair in the examination room, prepared to be mocked yet again by my favorite doctor.

It hurts when I bang into things

…I thought to myself, rubbing the bruise forming on my leg. If there was a second part to that sentence, it didn’t come to me.