o 132c9f47d7a19d14

Read o 132c9f47d7a19d14 Online

Authors: Adena

CONTENTS

1 2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1 0

1 1

1 2

1 3

1 4

1 5

1 6

1 7

1 8

1 9

2 0

2 1

THE SHAPE-CHANGER

Raudbjorn’s reason departed. With a terrible bellow, he drew his

sword and thrust it through Sorkvir to the very hilt. Planting his foot on

the wizard’s chest, he yanked the sword out and lashed off

Sorkvir’s head. Then he began to chop the rest of the wizard to pieces.

“Now you’ve done it, you berserk fool!” the eldest of the

Dokkalfar counselors shouted. “He’s going to change form!”

Raudbjorn staggered back in astonishment, coughing and

snorting. Instead of fresh blood, Sorkvir’s body oozed only dust.

Then a ghostly image began rising and swelling until it was as

large as Raudbjorn. It began to solidify into a massive, shaggy

bear. The small eyes in its enormous, broad head glowed redly. The

bear’s teeth parted in a menacing growl.

The wooden dais creaked as it padded forward toward Raudbjorn.

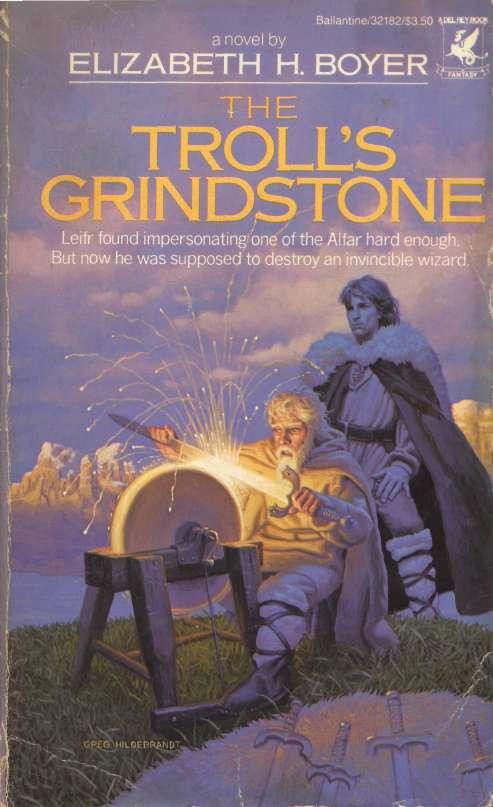

THE

TROLL’S

GRINDSTONE

Elizabeth H. Boyer

A Del Rey Book BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK

A Del Rey Book

Published by Ballantine Books

Copyright © 1986 by Elizabeth H. Boyer

All rights reserved under International and Pan American Copyright

Conventions. Published in the United States of America by Ballantine Books, a

division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by

Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 86-90852

ISBN 0-345-32182-0

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Edition: July 1986

Cover Art by Greg Hildebrandt

Some Hints on Pronunciation

Scipling and Alfar words sometimes look forbidding, but most

are easy to pronounce, once a few simple rules are observed.

The consonants are mostly like those in English. G is always

hard, as in Get or Go. The biggest difference is that J is always

pronounced like English Y as in Yes or midYear. Final -R (as in

Fridmundr or Jolfr) is the equivalent of English final -ER in under or

offer. HR is a sound not found in English. Try sounding an H while you

say R; if that’s difficult for you, simply skip the H—Sciplings would

understand.

Vowels are like those in Italian or Latin generally. A as in bAth

or fAther; E as in wEt or wEigh; I as in sIt or machIne; O as in Obey or

dOte; U like OO in bOOk or dOOm. AI as in aisle; EI as in nEIghbor or

wEIght; and AU like OU in OUt or hOUse. Y is always a vowel and

should be pronounced like I above. (The sound in Old Norse was

actually slightly different, but the I sound is close enough.)

Longer words are usually combinations of two shorter words or

names. Thus “Thorljotsson” is simply “Thorljot’s son” without the

apostrophe and joined together.

And, of course, none of this is mandatory in reading the story;

any pronunciation that works for the reader is the right one!

Leifr had not expected any company when he made his furtive

encampment among the old barrows of Morken. Someone, however,

was out there moving stealthily among the stones, watching him.

Quickly he stamped out his small fire and listened again, straining to

hear over the hissing of the icy wind that was parting the sere grasses of

the barrows and moaning among the lintels of the barrow mounds.

Thinking of the restless draugar, he burrowed into a pouch to

find a small gold hammer, which was his last possession of any value

worth considering. Hanging the amulet at his throat, he next thought

about the three thief-takers pursuing him for the reward on his head.

The best defense against those human predators was already gripped in

his hand—a precious steel sword he had taken from a dead enemy while

he sailed with the viking Hrafn Blood-Axe.

After a long, taut wait, he heard the stealthy crunch of dry grass

under a foot, coming from the direction of a small round barrow to the

north. Using the lowering gray twilight to conceal his movements, Leifr

slipped around the edge of the barrow, approaching the small

tumulus. Crouching behind an upright stone blackened with ancient

lichens, he waited until another soft sound belied the intruder’s hiding

place. Leifr crept forward soundlessly.

A cloaked figure crouched behind the largest stone of a ship ring,

peering intently around the edge toward Leifr’s extinguished fire.

Silently Leifr crept forward, still undetected, drawn sword in hand.

Then with a rush and a pounce, he seized the spy by the collar, flung

him back against the stone, and held him frozen there with the gleaming

point of the sword inches from his throat. The stranger gasped for

breath, his eyes held in fascination on the poised sword. After a brief

appraisal, Leifr had to admit to himself that his captive did not

resemble a thief-taker. Skinny, ragged, possessed of no weapons or

armor, the stranger more resembled one of the emaciated corpses in

a barrow.

“Who are you, and why are you spying on me?” Leifr put as

much menace as possible into the questions—an unnecessary

precaution, considering the fellow’s condition.

The stranger transferred his shadowy gaze to Leifr’s face. “All I

was hoping for was to beg a share of your fire, and perhaps your food if

you have any to spare.”

“You’re a wanderer?” Leifr asked suspiciously. The man nodded

briefly. “Landless, lordless, and frequently foodless. I get most of my

living from scavenging bits of metal, bones, and hides. 1 also render

tallow from time to time, when I can find an unclaimed carcass.”

Leifr’s eyes narrowed incredulously, and he darted an uneasy

look around the barrows to see if any of them were recently opened.

“No, no, animal carcasses,” the scavenger hastened to explain.

“The tallow is for making candles.”

Slowly Leifr lowered the sword, considering the scavenger.

Although he certainly looked like a destitute scavenger and he spoke

with a certain degree of forced servility, there was a disturbing note of

self-mocking deprecation in his speech, as if he found a source of grim

amusement in his desperate situation.

“You don’t speak like an outcast,” Leifr said.

The stranger returned Leifr’s scrutiny with an unabashed

stare. “I wasn’t born to this lot, which is sometimes a great

disadvantage. People think I’m an impostor.”

“Impostor!” Leifr chuckled ironically. “Who would want to be

mistaken for a scavenger, if he weren’t one?”

“A good question indeed,” the scavenger replied with a faint,

quirking smile. “Show me there’s no weapon under your cloak, and I

expect I can let you share my protection tonight,” Leifr said. “There

are some outlaws and thief-takers prowling around this barrow field

tonight, and there’s not one of them you’d like to run into unawares.”

The scavenger opened his cloak to the bitter wind, revealing no

weapons— merely an assortment of castoff shirts and tunics hanging to

his knees in tatters blackened by grease and soot, some disreputable old

trousers, and a pair of ancient, reindeer boots with most of the hair

rubbed off and with holes where the grass stuffing was coming out.

Only a very ingenious lacing job prevented the boots from falling

completely apart. Leifr also observed that the stranger’s right arm

dangled uselessly in its sleeve—perhaps damaged in a long-ago defense

of his former lord. In spite of his wasted and battered appearance, he

seemed unbeset by advanced age; what his true age might be, Leifr

was unable to guess. Disfiguring scars, obviously of early vintage,

had drastically marred the fellow’s countenance with swollen white

seams. Leifr surmised that most of the bones in his body must have

been broken and allowed to heal with painful crookedness to lend the

stranger such a raddled and unwholesome appearance.

“Not a splendid sight to behold, am I? Except for a curiosity,

perhaps,” the scavenger observed wryly. “Once I looked like a fine

specimen of a warrior, much like yourself—instead of a crushed beetle

scrabbling around, half-alive.”

Leifr squinted at him dubiously. “If that’s true, then I suppose I

could believe almost anything.”

“I’m glad to hear it. Are you satisfied yet that I’m nothing but a

wretched old beggar, of no possible threat to one such as yourself?”

Leifr did not doubt the creature’s wretchedness, but it seemed

that he was making too much of the oldness, so Leifr’s well-

conditioned suspicions lingered. The wizened scavenger’s beard

was still black and wiry, although Leifr had no way of telling how

much of its color might have been attributable to soot and grease.

“You’ll do,” Leifr said. “You look almost as destitute as I am

right now. I’m afraid that my hospitality is little better than a fire and

some stale bread.”

“It’s better than nothing, on a night like this.” With a sigh of

relief, the scavenger stooped to pick up a sack with some lumpy

bulges in its sides and followed Leifr back to the camp by the lintel.

Leifr relit the fire, tore in half a round black loaf of bread, and

used his knife to divide a shard of hard, rank-smelling white cheese.

“You’re generous to a fault.” The scavenger accepted the cheese

extended on Leifr’s knife point. “Only a poor man shares so willingly.”

“Having so little to share makes it easier. Half of almost nothing

is no sacrifice at all.”

They sat chewing the meager provender in companionable

silence, each studying the other with covert glances. “A barrow field is

an unhealthy place to stop for the night,” the stranger observed,

brushing the crumbs out of his beard and catching the ones that he

could. “There are friendly houses hereabouts that let a stranger in from

the cold and dark.”

“So why didn’t you find one?” Leifr retorted suspiciously, shying

away from the subtle questioning. “I have my reasons for choosing this

place, and if yours are similar to mine then the less said about it, the

better.”

“Quite so.” The stranger nodded. “I had you pegged from the first

moment I saw you and your fire. No horse, no companions, a small

huggermugger fire in an unfrequented place— you’re an outlaw,

running from thief-takers, perhaps.”

“It’s not wise to be so curious, my friend,” Leifr warned.