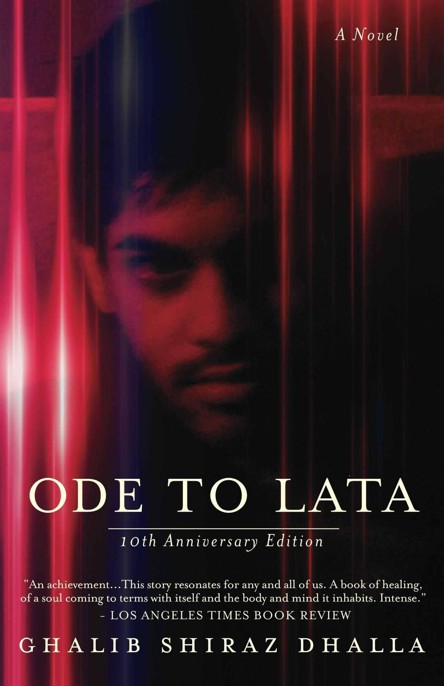

Ode to Lata

Authors: Ghalib Shiraz Dhalla

Tags: #Bollywood, #Ghalib Shiraz Dhalla, #LGBT, #Gay, #Lesbian, #Kenya, #India, #South Asia, #Lata Mangeshkar, #American Book Awards, #The Two Krishnas, #Los Angeles, #Desi, #diaspora, #Africa, #West Hollywood, #Literary Fiction

Praise for Ghalib Shiraz Dhalla and

Ode to Lata

“An achievement. Dhalla traces the history of a life over three continents, through three generations of a family, exploring multiple facets of human sexuality in the process. This story resonated for any and all of us. This is a book of healing, of a soul coming to terms with itself and a body and mind it inhabits. Intense.”

Los Angeles Times

“A devilish indulgence. Kudos for creating Ali, a chatty, outrageously embittered protagonist.”

Publishers Weekly

“Much more than a ‘coming out’ story, this is a brilliant study of culture, religion, body image, racism, sex, and friendship that cuts to the soul. Dhalla’s first novel will touch anyone who has felt out of place, unattractive, and unloved. Highly recommended.”

Library Journal

“Dhalla turns gay life from cliché to reality as few other novelists have as he tells Ali’s story in a racy, edgy manner that is delicious to read.”

Booklist

“Dhalla’s undeniable narrative power carries the reader through an emotional terrain where West Hollywood nightclubs and ancient Kenyan mosques stand side-by-side. His insights into questions of sexuality and race help craft a universal tale of longing, loss and the capacity for change. It is a rare, great novel that manages to be both deeply sad and ultimately uplifting.”

Christopher Rice,

NY Times

bestselling author of

A Density of Snow

and

The Snow Garden

“Poignant. Dhalla has found his voice and given one to an entire community.”

Out

“Talk about multiculturalism, this book has it all. Last year’s Nobel Prize for literature was won by V.S. Naipaul. In Ghalib Dhalla, we may just have the gay V.S. Naipaul.”

- Orange County Blade

“A multicultural gem that transcends all borders of race, ethnicity, and sexuality. The sharply written story of Ali unravels like a beautiful tapestry, treating the readers to exotic locales and universal longings.”

Mark Jude Poirier, author of

Goats

and

Naked Pueblo

For more advance praise, interviews and media, please visit

Bonus short story, "A" follows at the end of this book.

ODE TO LATA

GHALIB SHIRAZ DHALLA

A NOVEL

AUTHOR’S EDITION

Ode To Lata, Author's Edition

Copyright Ghalib Shiraz Dhalla ©2011

Digitally (ebook) Published by: Final Word Books

All Rights Reserved

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author's imagination of are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Cover Art Design: Warner Alas

Photo of Sachin Bhatt (Ali) in "The Ode" by Ghalib Shiraz Dhalla.

Digital book(s) (epub and mobi) produced by: Kimberly A. Hitchens,

[email protected]

FOR PARVIZ

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Victor Riobo, Israel Velasquez and Deborah Ritchken.

Gone, inner and outer,

no moon, no ground or sky.

Don’t hand me another glass of wine.

Pour it in my mouth.

I’ve lost the way to it.

–RUMI

Ghalib Shiraz Dhalla

CHAPTER 1

THE SNAKE

There are only two things in life worth living for; passion and truth. Passion came to me in plenty, but the truth it seems, eludes me still.

I’m driving down the Los Angeles snake, this creature upon whose curvature our lives have been unwittingly trapped, trudging along at twenty miles per hour in a sea of cars. It’s 7:59 and I’m afraid that I will miss the first half of

Melrose Place

. That is all that concerns me at this moment. That my auxiliary family of vixens, faithless men and a token gay man, will move on and deprive me of the vicarious pleasure of their lives, leaving me mired in my own.

The night before had been the search for the bed of yet another stranger’s bed to wake in; the morning the start of another mechanically meaningless day and my insatiable hunger for Richard.

On the radio the news reports of another drive-by shooting, and then of the massacre of two young men – a possible hate crime. I switch the station to some dance music and revert to modern man’s shield against the tyranny of the city: apathy. Too depressing. It doesn’t concern me. It’s not my problem. I have my own to worry about. Reality has grown so harsh, so unforgiving, that paradoxically, only the mundane, the absolutely frivolous is able to elicit any concern anymore. I don’t want to know how the disgruntled, bi-polar man managed to buy a gun, or why he stormed the offices and sprayed his now disowned family of ex-co-workers with bullets; I only want to know if Amanda will get promoted at the agency and if that psychotic Sidney will manage to seduce the young buck dating her sister.

I gaze at the American flag hoisted up the pole of a building just off the freeway as I grudgingly bring the car to a standstill again. The image of the Kenyan flag with its brilliant red and green colors flashes through my mind and the traces of a smile tease the premature gauntness of my face. I think about all that the American flag in front of me has meant to people everywhere. What it had meant to me. Its impregnable promise of benevolence.

It occurs to me that this flag was very much like those three-dimensional prints that everybody gazes at in the malls these days. Squinting, waiting, hoping for a vision to appear. It was only when the tentativeness gave way and you were pulled into its panoramic window that your heart began to sink, and the mesmerizing specks of color integrate to reveal an unexpected aftermath.

I remember first seeing that flag up-close eight years ago. I must have been on the fifteenth floor of a building in Kenya that housed the American embassy, applying for my visas. My mother sat close to me, half dreading the impending departure of her only son – barely a man, still her boy – and I, quite insensitive in my exhilaration, sat transfixed at the sight from a window in the lobby. It flapped authoritatively in the wind, imbuing me with such hope that I felt as if I were already there.

It was a moment my entire life had been leading up to. The beginning of a new life of adventure and possibility that Kenya could never offer me. A place with people I had never met, far away from those whom I had known. The excitement of forging an identity independent of them overruled any trace of sentimentality. I would miss them all, but who cares, right? Soon they’d all talk about me. The one who got away. Someone would undoubtedly start a rumor about how I’d become this big star living in a flashy apartment and driving an expensive car in L.A. and boy, would they roll those two initials when speaking! EEI-LAY! With a thrust of the hand, that gesture that looks like a pigeon released into the air, a sign of deep mysteries and awe. Of course they would never know for sure, but the touristic postcards I would send home – and the Indian capacity for exaggeration – would assure my fame and glamour. It was all waiting there for me, this unconfined life, and the door was about to open and let me in.

I look at that flag now, and suddenly it’s not all so simple. Hollywood Boulevard is not adorned with stars as much as it is littered by hookers and pushers who contrast the memorable sidewalks with their own agitated lives. Beverly Hills serves as little more than a foil to the barrios of East L.A. Downtown looks pretty only from a distance at night, engulfed by the darkness that cloaks its destitute, the lights of office buildings gaping like empty, hollow eyes at marveling tourists. The Los Angeles of Jackie Collins novels, which I had devoured as rudimentary to my introduction to the city, is nowhere to be found but in the pockets of a privileged few.

Now, I’m no longer a spectator gazing at the print. I’ve leapt into its dimension and I’m one of those little colored specks that constitute the big picture. It stands there, stealing some of the light from the bright Arco gas station sign behind it, brandishing itself petulantly in the wind, flapping and employing its most critical acting talent to appear immaculate in the putrid L.A. smog.

Hell, in this city everyone needs a good publicist.

CHAPTER 2

IMMACULATE CONCEPTION

Whenever she had the choice, my mother preferred taking the train over the arduous six-hour bus ride, or even the elite hour-long commuter flight from Mombasa to the capital city of Nairobi.

The East Africa Railway, engineered by the British in 1896 and largely built by immigrant Indians, was responsible for the exodus that brought my ancestors to Kenya. It represents, even now, the romanticism of colonialism – a different type of mechanical snake, one that undulated through the verdant land its creators once tried, albeit in vain, to tame. As the seductive plains opened like thighs, Africa enveloped us in her limbs. Years from then, in another corner of the world, even a faint smell, a flash of sight, a distant sound would send a chill of nostalgia up some part of my body, and for a split second, standing in a crowded mall or in the elevator of some skyscraper, I felt as if I was back there; that it had somehow, miraculously, projected itself onto my realm.

I had found freedom in geography only to be forever captured by the memories of the home I left behind. In my dreams, I still ride the railway. Listen to all the sounds and senses that are Kenya: Swahili songs from village women clad in colorful and light cotton batiks, delicately balancing baskets of fruits and vegetables on their heads; urchins and villagers who keep pace with the train, awaiting the arrival of fresh customers at stations to buy their hardboiled eggs, biscuits and roasted maize pressed with lemons and chilies; at dawn, the animals of the land respond to our exhilaration with pure indifference; and upon arrival, the chaotic sounds of reunions, departures and coolies who compete to ferry our luggage to the car. And always that smell, that distinct perfume of Kenya, a smell of salt as the breeze comes off the ocean, of food cooking on wood fires and mingling with diesel smoke, of the sweat of hard labor everywhere.

As we chugged along such a journey, my mother could always be counted on to tell me two things. That it was on such a ride one balmy evening, albeit in the reverse direction, that I had been conceived, a story that increased in detail and waned in credibility with each rendition.

“You know,” she said, her eyes widening and one hand flipping up to express amazement. “We never even had, you know, proper intercourse!”

She maintained that on that life-altering night simple peripheral contact had impregnated her, lending an almost mythic prowess to my parents’ virility and a sense of destiny to my close-to-immaculate conception.

“Your father and I – all we had to do was touch each other and I would become pregnant!”

Contrary to expectation, such details never made me feel even faintly uncomfortable. Rather, they served to inspire me in finding such a marvelous love story of my own.

Perhaps the memory of their lovemaking that night is why melancholy would unfailingly seize her at certain points of the journey and she could be found staring out the window at the fleeting land, her tongue struck silent in her mouth; as if she was, years after my father’s demise, reliving that very experience in the same compartment. It was the same look that came upon her when, listening to an old cassette of

filmi

music on what we called an impressive three-in-one (radio, tape and record player), a song that my father had loved would unexpectedly play. At these moments, it was enough just to look at her and know that so much of her innocence, her idealism of love, her zeal for life (a part of herself) had also died with him. At these moments, she was completely lost to the world that had carried on without his existence, and she could not fathom why.