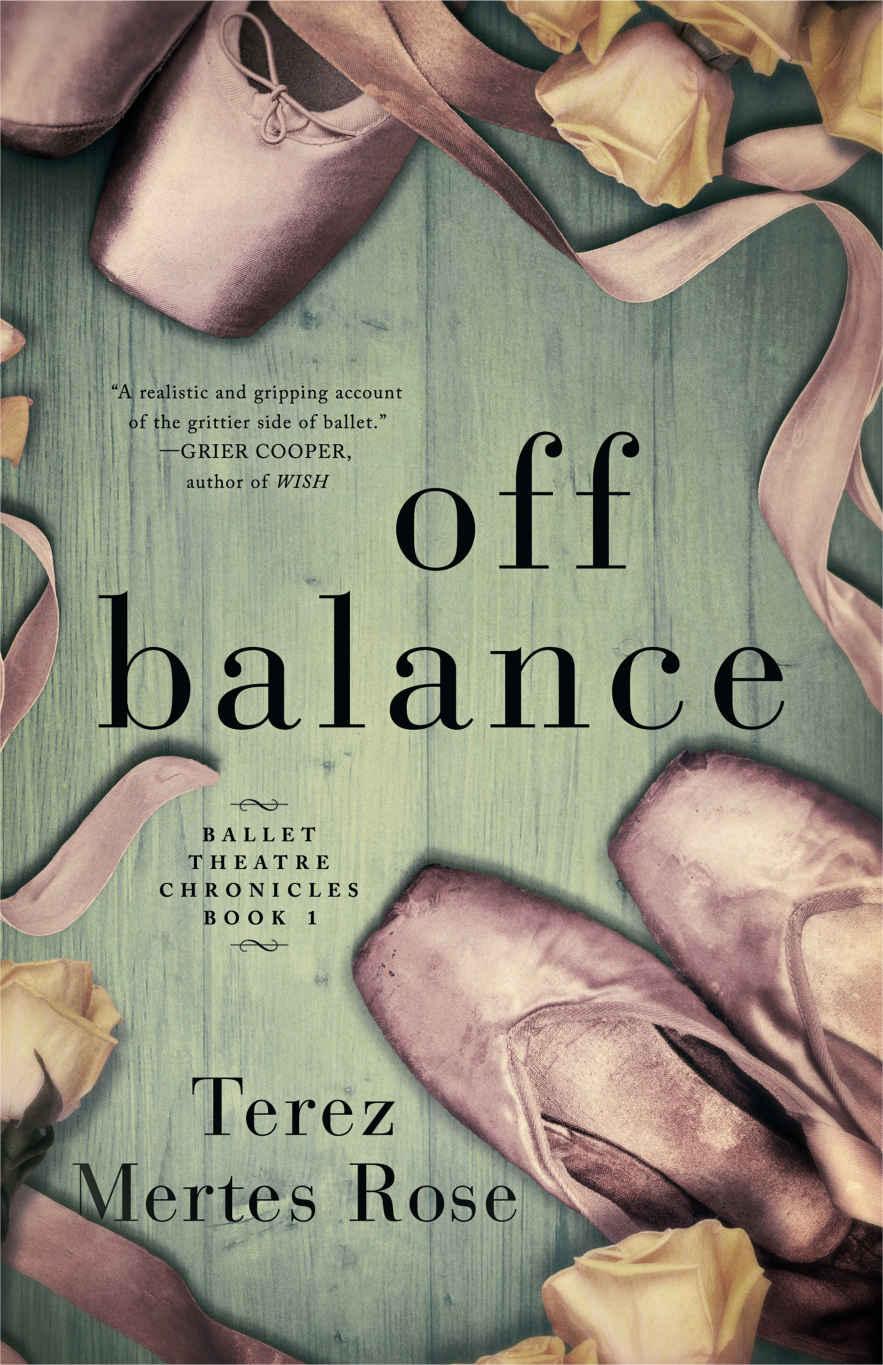

Off Balance (Ballet Theatre Chronicles Book 1)

Read Off Balance (Ballet Theatre Chronicles Book 1) Online

Authors: Terez Mertes Rose

Ballet Theatre Chronicles, Book 1

A Novel

Terez Mertes Rose

Copyright © 2015 by Terez Mertes Rose

All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the author and publisher, except when permitted by law.

Off Balance

is a work of fiction. The West Coast Ballet Theatre is a fictional dance company, a composite based on information culled from five major U.S. dance companies. All events, schedules, individuals, organizations and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or have been fictionalized. Any resemblance to actual San Francisco events or persons is coincidental.

Published in the United States

Classical Girl Press -

www.theclassicalgirl.com

Cover design by James T. Egan, BookFly Design, LLC

Formatting by Polgarus Studio

ISBN-13 978-0-9860934-0-1

ISBN (ebook) 978-0-9860934-1-8

For Peter and Jonathan, with love and gratitude

“The only way to make sense out of change is to plunge into it, move with it, and join the dance.”

— Alan W. Watts

Spring Season 1997

On Saturday night Alice Willoughby’s world, her glittering soloist’s career, came apart with a single misstep executed in front of 2000 spectators at San Francisco’s California Civic Theater. Rendered careless by fatigue, she’d prepped wrong and the next step into an arabesque en pointe proved to be her last. A curious pop sounded, her knee gave out and she fell to the black, slip-resistant marley floor. She heaved herself to sitting, adrenaline surging through her, stunned by the realization that she couldn’t get up any further. Her left knee simply wouldn’t cooperate. The pain was like an explosion, obscuring everything but the mantra drummed into her after twenty years of ballet.

The show must go on.

Without breaking character.

Ben, her partner that night, immediately caught on to the situation. He made his way over to her, via a series of grand-jeté leaps to give the illusion that they were still dancing, that her fall had merely been part of the ballet.

Time slowed to a psychotropic-hued crawl. She seemed to be watching herself, her brain whirring uselessly, her limbs dumbly splayed out. Her gaze swung to the right, past the blazing stage lights, where she saw the other dancers now crowding the wings, jaws slack in horror. April, the ballet mistress, was standing in the middle wing, crying out, “She’s down! She’s not getting up!”

The voices sounded tinny and yet piercingly clear, as if transmitted through a long metal tube. Although the audience heard only the orchestra, she could hear the stage manager calling out to April, “What are they doing? Do we end? Lighting’s asking me,” and April’s, “She’s hurt, someone get Lorraine back here,” and the stage manager’s tense voice saying into his headpiece, “I don’t

know

what they’re doing, Larry, okay?”

"We’ll wing it," Ben called out through the corner of his mouth, like a ventriloquist. “Give us sixty seconds.”

He swooped behind Alice and helped her rise from her sitting position onto her good leg. Somehow, in spite of the state of shock she’d descended into, she managed to shift her bad leg behind her and strike a pose, swaying like a drunken corps de ballet dancer, yet raising her arms to a grace-laden fourth arabesque position, arms at ninety degrees.

This shouldn’t be happening,

her mind kept crying out.

It couldn’t be happening.

But it was.

They improvised through the last minute of their pas de deux variation, the third-to-last movement of the ballet, Ben murmuring cues to her every time his back was to the audience. He’d lift Alice lyrically and set her down a few steps later. She’d hold the pose as he executed a series of movements, here a stylized lunge, there a few steps into a sharp, clean, triple pirouette. Gone for her, the fast-paced, rigorous choreography, but she still had full control of her upper-body presentation, employing expressive hand and arm movements until Ben returned to haul her to another part of the stage.

“Can you do the big lift?” he panted in her ear thirty seconds later.

She was trembling with spent adrenaline, losing energy fast. “Have to,” she said through gritted teeth, never dropping her serene stage smile. It was their final departure from the stage, the last thing the audience would remember. It couldn’t be half-assed.

“Okay, hang tight,” he murmured. Placing one hand on her right hip and the other under the thigh of her bad leg, he hoisted her high above him.

The pain of it took her breath away. Sweat, and now tears, stung her eyes as she arched back, gaze high, arms in high fifth. She pressed her good leg up against the maimed one, as a human splint. She knew she must be cutting a sorry figure, and yet even this seemed to encompass the mood of the ballet.

Tomorrow’s Lament

was its name. Fitting, that.

She kept her expression regal, her arms high, as Ben wafted her offstage. The conductor of the orchestra, alerted to the plan change, allowed the music to grow softer before subsiding, thirty-two measures early, on a haunting note.

Perfect silence, as the stage faded to black.

The audience seemed to take one great, collective inhale before they burst into applause, cheers and calls of “

brava

,” which grew louder as Ben eased her down backstage.

“Oh, Alice,” the other dancers cried, crowding around her, reaching out to touch her arm, her knee. The assistant stage manager whisked over a chair and she slid into it.

“Oh, Alice,” April cried, hurrying to her side.

“Oh, Alice,” Lorraine, the physical therapist said, shaking her head as she probed at Alice’s knee, her ankle.

Ben returned from his solo curtain call as the audience roared their approval. “Alice, they want

you,

” he said, half-laughing, half-crying.

“They can’t have her.” Lorraine sounded grim. “She’s not going anywhere.”

They’d been the pas de deux couple for the third movement. A trio of dancers stood waiting to take the stage for the fourth movement, which would be followed by the finale, an ensemble movement. Alice, however, was done for the night. Even now, they were summoning a substitute dancer to the wings, to don Alice’s costume and replace her for the finale.

The applause hadn’t stopped. The dancers in position to go on next had to wait as the stage manager cued Ben for another curtain call. When he appeared, the audience exploded into louder applause, over which could be heard shouts and clamors. For Alice.

“Damn,” said the stage manager, observing the scene on his monitor. “They really do want her.”

They were calling for her. Begging. It was a childhood dream come true.

Except for the pain.

So began the euphoria—the thrill of having turned an onstage accident into a triumph, the glow of so much attention—a high so deeply intertwined with the pain that it was difficult to know where one ended and the other began. Until the euphoria faded and the pain didn’t.

Until the other dancers returned to company class on Monday morning and Alice returned to the hospital for surgery.

Until a new cast list was posted for the next performance that didn’t include Alice’s name. Nor would it, for some time to come.

It wasn’t until two weeks later, however, that reality finally sank in. She was at the medical clinic for a follow-up appointment with the orthopedic surgeon. Earlier in the day, she’d buoyed herself with the idea of taking college classes, something deemed unnecessary, even preposterous seven years earlier, upon high school graduation. She’d wanted only to be a soloist with San Francisco’s renowned West Coast Ballet Theatre. But now, soloist position on hold, she recognized the importance of a temporary diversion. Further, it would serve to wake up that analyzing, information-seeking part of her brain, dormant since school days.

“Don’t think,” Balanchine used to tell his New York City Ballet dancers. “Don’t analyze. Just dance, dear.”

She endured the doctor’s appointment with its disappointing news and decided that, yes, college classes were a must. She’d drop by San Francisco State’s admissions office that very afternoon.

As she crutched her way toward the clinic’s exit, she spied a vending machine. It sold, among other high-caloric, low-nutrition snacks, Snickers bars.

When was the last time she’d allowed herself a Snickers, just for the hell of it?

She fed the machine a five-dollar bill and pressed the correlating button. The familiar brown-wrapped bar thunked down. Afterward her fingers hovered over the return-change button. She thought about the doctor’s words, his “hmm, usually we like to see better progress around now,” as he’d studied X-rays of her leg, showing the ankle fracture—a bonus injury she’d discovered only later—and the knee’s torn ligaments. Something inside her gave an uneasy flicker.

In an adjacent trash bin, someone had thrown out a banana peel, but had missed getting it all the way in. It hung there now, two yellow limbs clinging to the exterior. It looked like a starfish, determined to climb out of the refuse pit, a quixotic, ill-fated endeavor if there ever was one. She studied the peel, this little blot of stubborn, misguided optimism against this huge landscape of antiseptic order and barely masked unwellness.

That was her. That speckled banana peel, whose too-sweet aroma carried over, competing with the iodine and ammonia smells. Reality engulfed her, like a big bucket of water. She was screwed. She would have staggered if she hadn’t already been on crutches.

Five miles away, her colleagues had just finished company class. They’d be leaving the studio together, leotards saturated with sweat, dance bags slung over their shoulders, griping about last-minute casting changes, aching joints, wondering aloud if there were time for a catnap between rehearsals and the evening’s seven o’clock theater call. For them it was just another day. And here she stood, alone, bad news percolating through her, seeing the glacial, uncaring nature of the world as if for the first time.

No wonder Balanchine didn’t like his dancers to think.

The Snickers bar lay in the trough of the vending machine, the credit balance displayed in glowing red numbers on the machine’s face. In a frenzy, she began punching the designated number, three times in rapid succession. Down came more Snickers bars, one clunking after another, a satisfying

thunk, thunk, thunk

.

Grabbing them all, she shoved them into her backpack and made her way clumsily over to a padded bench in the corner. After she got herself and her encased leg situated, she tore open the first Snickers and took a bite. The flavors exploded in her mouth, alongside the recognition that she now had the freedom to eat this. She would not be wearing any skintight, paunch-exposing costumes any time soon.

Three more bites finished the first bar and she started right in on the second. The shock of the pleasure was like great sex after a year of celibacy. The chocolate and caramel, the mysterious “nougat” and peanuts. The sugar. The hint of saltiness providing complexity. A sigh escaped as something intractable inside her yielded to the pleasure.

She hesitated over the third one. Somehow it penetrated her stimulus-fogged mind that this was not about sensory gratification anymore. If she decided to eat more, it was because she understood somehow, deep down, that she would not dance onstage again.

“It’s not over,” the orthopedic surgeon had encouraged her, following his “this isn’t looking good” analysis. “All professional dancers have setbacks.” He’d offered stories of dancers who’d suffered broken limbs, torn ligaments, crushed feet, coming back to lead roles. Her friends—all dancers, because who had time to cultivate any other kind of friendships?—had tried to feed her the same kind of pep talks.

She unwrapped the third bar.

How did she know it was over?

She just knew.

She began to cry, she who never cried, above all in public. Since her earliest years, such a display had been taboo. She remembered her mother, back when she was alive and hadn’t yet taken sick: the indomitable Deborah Whittier Willoughby, marching the six-year-old Alice right out of a ballet class, scolding her the entire way to the car. Alice had been crying, upset because her rival had been chosen to play the lead daisy in the recital.

Deborah had been unforgiving. “And in front of everyone,” she’d hissed. “You’re a Willoughby. Shame on you.”

But Deborah was not here now, which struck her, even fourteen years after her death, as one more thing to cry about. Instead it was Alice, her loss, and the remaining Snickers bars. She held up the third one and sank her teeth into it. She continued to cry, softly, as she ate, helpless to stop either act. It was exquisite pleasure and agony at once, swirled together like soft-serve ice cream that came out half chocolate, half vanilla.