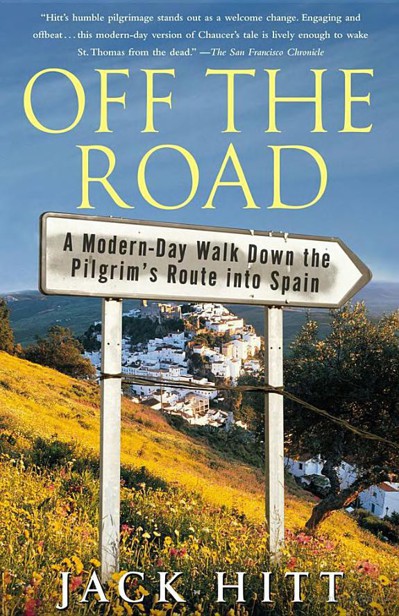

Off the Road

Authors: Jack Hitt

First published in

Great Britain

1994 by Aurum Press

Limited,

25 Bedford Avenue,

London WC1B 3AT

Copyright © Jack Hitt

1994

The extract from

The

Pilgrim's Guide to Santiago de Compostela

by Annie

Shaver-Crandell, Paula Gerson and Alison Stones is reproduced by kind

permission of Harvey Miller Publishers.

All rights reserved. No

part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any

information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from

Aurum Press Limited.

A catalogue record for

this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN I 85410 306 7

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

1998 1997 1996 1995

1994

First published in the

USA by Simon & Schuster

Printed in Great

Britain by Hartnolls Ltd, Bodmin

[email protected]

v1.0

27.01.2014

CONTENTS

For Lisa

OFF THE ROAD

L

ike many my age, I effortles

sly cast off the religion of my parents as if stepping out of a pair

of worn trousers. It happened sometime a

round college back in the 1970s and

therefore was done with the casual arrogance and glibness famous to that time.

I remember lounging in the last row of my required religion class. Professor

Cassidy was making some relevant point, and I popped off that I would happily

sum up the closed book of Western religion: The Jews invented god, the

Catholics brought him to earth, and the Protestants made him our friend. Then

god suffered the fate of all tiresome houseguests. Familiarity breeds contempt.

With that, we dragged him into the twentieth century to die.

Afterward, the other

sophomores and I ran off for the woods, read aloud the poetry of Arthur

Rimbaud, and lit one another’s cigarettes with our Zippos.

Let me say that my general

attitude about religion has mellowed since then into a courteous indifference.

On most days I side with the churches and synagogues in the everyday political

battles that are called “religious” by the papers. My libertarian bent tilts

enough against government that I don’t get too excited about people who want to

pray in schools or erect crèches or Stars of David in front of City Hall. And

yet, if I’m angry or have been drinking, I am quick to say that when it comes

to goodwill on earth, religion has been as helpful as a dead dog in a ditch,

and that in this century it’s been little more than a repository of empty

ritual and a cheap cover for dim-witted bigotries.

So, imagine the reaction of

many of my friends and relatives when I announced that I was going on a

pilgrimage. And not some secular skip up the Appalachian Trail, but an ancient

and traditional one. I intended to retrace the famous medieval route to Santiago de Compostela, Spain. Tucked into the northwestern panhandle of Spain on the Atlantic, Santiago is a few miles inland from Europe’s westernmost spit of land,

Finisterre. As its name implies, it was the end of the world until 1492. The

road began in

a.d.

814 when a

hermit in the area stumbled upon the body of Saint James the Apostle. Since

then, the road has been walked every year—in the Middle Ages by zealous

millions; in more recent times by curious thousands.

For most of the late

twentieth century, pilgrims to Santiago followed the shoulder of a blacktop

highway paved by Generalissimo Franco. Then in the early 1980s scholars based

in Estella, Spain, reacted to public concern after at least four pilgrims had

been run over by trucks. Using old maps and ancient pilgrim accounts, the

historians recovered vast sections of the original footpath still serving as

mule or cart routes between the hundreds of poor villages along the way.

Sections of the road were also intact in France, but once a modern pilgrim crossed

the Pyrenees into Spain, there it was: a slightly wrinkled beeline of eight

hundred authentic kilometers due west, following the setting sun by day and the

streak of the Milky Way by night—over the craggy hills of the Spanish Basque

territory, into the wine valleys of Rioja, across the plains of Castille,

through the wheat fields of León, over the alpine mountains of Galicia, and

finally into the comfort of the valley of Santiago. Depending on where I

started, the walk could take two months, maybe more. Since pilgrims are

supposed to arrive in town just before James’s feast day on July 25, the idea I

had in mind could not have been more simple and appealing. I would fly to Europe and spend the belly of the summer walking to the end of the world.

Despite my many, obvious

disqualifications for being a pilgrim, I have long had an interest in the

tradition of walking the road. After all, one could dress it up with all kinds

of rationales and ritual, but stripped down, a pilgrim was a guy out for some

cosmically serious fresh air. So in the beginning, it was the very simplicity

of the idea of pilgrimage as a long walk that attracted me. Little did I know.

The medieval argument for

pilgrimage held that the hectic routine of daily life—with its business obligations,

social entanglements, and petty quarrels—was simply too confusing a pace for

sustained thought. The idea was to slacken that pace to the natural rhythm of

walking. The pilgrim would be exiled from numbing familiarity and plunged into

continual change. The splendid anarchy of the walk was said to create a sense

of being erased, a dusting of the tabula rasa, so that the pilgrim could

consider a variety of incoming ideas with a clean slate. If escaping life’s

hectic repetition made sense in the Middle Ages, when time was measured by the

passing of day and night, then it seemed to me reasonable to reconsider this

old remedy now that we schedule our lives by the flash of blinking diodes.

This idea was a lot more

than a Saturday hike or weekend outing. A pilgrimage would mean subletting my New York apartment, quitting my job, and resigning from my generous health plan. I would

live on foot, out of a backpack, among old pueblos—some unwired for

electricity, others abandoned centuries ago to become stone ghost towns. My

long-set routines would be shattered, and my daily responsibilities would

evaporate. I’d walk out of the pop-culture waters in which I had spent a

lifetime treading and onto a strange dry land. I’d be far, far away from the AM

hits that leak from cars and malls and dorms. I’d be at a blissful remove from

CNN headlines and last night’s news. I wouldn’t have an opinion on whether the

wife was justified in shooting her husband or whether the cop thought the

ghetto kid was reaching for a knife or whether the woman had consented before

the rape or whether the nanny had accidentally dropped the baby from the

window... because I wouldn’t know a single fact. My mind and attention would be

cleansed of all that, and I could discover what topics they turned to when so

generously unoccupied. A long walk. A

season

of walking. As it happened,

I had just reached the Dantean age of thirty-five. What better way to serve out

my coming midlife crisis than on a pilgrimage?

I quickly found, though,

that one cannot discharge a word like “pilgrimage” into everyday conversation

and long remain innocent of the connotations that drag in its wake. I had spent

the last decade working as a magazine writer and then as an editor at

Harper’s

Magazine.

When I began to speak of my idea to associates throughout the

media, I sometimes encountered polite interest. More often, I’d hear a bad

joke. “Yo, Jack Quixote.” A famous New York agent told me that if I found god,

to tell him he owed her a phone call.

Those who were interested

enough to keep talking would sometimes pinch their eyes as if to get a better

view. Their lips crinkled in apprehension. Their fear, of course, was that I

might return from Spain with an improved posture, a damp smile, and a lilac in

my hand.

As a Western practice,

pilgrimage is not merely out of fashion, it’s dead. It last flourished in the

days of Richard the Lion-Hearted, and it was one of the first practices Martin

Luther felt comfortable denouncing without so much as a hedge. “All pilgrimages

should be abolished,” were his exact words. As something to do, the road to Santiago has been in a serious state of decline, technically speaking, since 1200.

The problem with pilgrimage

is that, like so much of the vocabulary of religion, it is part of an exhausted

and mummified idiom. We know this because that vocabulary thrives in the

dead-end landfill of language, political journalism. Senators make pilgrimages

to the White House. The tax cut that raises revenue is the Holy Grail of

politics. Clean-cut do-gooders such as Bill Bradley and John Danforth are

saints. The homes of dead presidents are shrines. Any threesome in politics is

a trinity. Mario Cuomo doesn’t speak, he delivers sermons or homilies. Dense

thinking is Talmudic or Jesuitical. Devoted assistants are apostles.

The connotations of what I

was doing hadn’t deterred me because, before I went public, I had decided to

walk the road on my own vague terms. I didn’t foresee how much the implications

of this word would overwhelm my own sense and use of it. In America, for whatever reason, any discussion of Christianity eventually gets snagged on an

old nail. As a Christian, you are forced to answer one single question: Do you

or do you not believe that Jesus the man was god the divine? If you can’t

answer that question easily, then you’ll have to leave the room.

It is strange—and I say this

without cynicism or bitterness— how

little

that question interests me,

especially as a pilgrim. In fact, the weighty topics of theology intrigue me no

more today than they did in Professor Cassidy’s class. I realize it is apostasy

as a pilgrim to admit this. But all those ten-pound questions— Does god exist?

Is faith in the modern age possible? Is there meaning without orthodoxy?—bore

me. The reason they wound up as running gags in Woody Allen’s movies is

precisely their hilarious irrelevance to the lives of many of us.

I think one reason religion

has become so contentious when it is expressed as politics (abortion, death

penalty, prayer in school, etc.) is that the answers to those Big Questions

can’t keep any of us awake. Thus, we turn to the hot-button questions about how

other people should live their lives. Religion has become a kind of nonstop PBS

seminar on ethics, conducted in a shout.

The result is that other

unarticulated notions and yearnings once associated with religion have become

intensely private. And that is why I wanted to walk to Santiago. At times it

seems that the average American feels more comfortable discussing the quality

of his or her orgasm on live television than talking about religion. I

wondered: What are these hankerings that are so intimate they cause widespread

embarrassment among my peers?

For me religion was always

bound up with a lot more than graduate school theology and those incessant

Protestant demands to believe in the supernatural. I grew up Episcopalian in Charleston, South Carolina. My family attended St. Philip’s Church, the oldest and most

prestigious church in a town that prides itself on being old and prestigious. I

served eight years there earning my perfect attendance pin in Sunday School.

And every time I walked through St. Philip’s twelve-foot mahogany doors, I

passed the same ten full-length marble sepulchers. Those nineteenth-century

vaults contain my great-great-grandparents. Inside the church, our family

always occupied the same pew and has, according to lore, since those folks in

the white graves sat there. Fixed beside the altar is a brass ornament honoring

a Charlestonian who died for his country. That man’s name is my name.

So, overthrowing the

religion of my parents was not merely a theological affair. It was tangled up

with my own ideas about the transmission of tradition, about honoring past

communities, and about forging new ones. I began to wonder just what else went

into the drink when I so handily gave religion the heave-ho. Now that I was

thirty-five, the vagaries of religion didn’t seem quite so irrelevant as they

did while I was refilling my Zippo with lighter fluid. More than anything else,

I needed to take a long walk.

Since I was troubled about

overthrowing the past, my long study of the even older tradition of Santiago seized my attention. The road had an Old World sense of discipline that I liked.

A pilgrimage is a form of travel alien to the American temperament. We

colonists like to think of ourselves as explorers, path blazers, frontiersmen

always on the lam and living off the cuff. Our history is an unchartered

odyssey, a haphazard trip down the Mississippi, or unscheduled stops along the

blue highways. When Americans are on the road, we don’t really want to know

just where we are going. We’re lighting out for the territories.

But a pilgrimage doesn’t put

up with that kind of breezy liberty. It is a marked route with a known

destination. The pilgrim must find his surprises elsewhere. I hadn’t the

slightest idea what this would eventually mean, but I liked the idea of

searching out adventure in the unlikely place of a well-trod road. There was

even a sense of gratitude in that to keep my days interesting, I would be

relieved of the usual devices of wacky coincidence or deadpan encounters with

the locals.

I also came to realize that

my word was offputting precisely because it retained a grubby literalism. A

pilgrimage was about sweating and walking and participating in something. The

word still had enough of its medieval flavor to suggest that one was submitting

to a regime, a task, an idea whose ultimate end would be discovery, even

transformation. “Pilgrimage”—those gravelly Anglo-Saxon consonants rolled

around in the mouth and came out ancient. It was evocative, imaginative, and

suggestive, I think, precisely because it was something so definable. For

example, if I had announced that my intention was to sweep through Europe to “study heaven,” no one would assume I had in mind a distinct piece of real

estate. But once upon a time, people did. The medieval worldview held that the

blue sky above us was a plasmatic skin literally separating us from heaven. The

engineers of the tower of Babel had nearly climbed up to it and were punished.

Today, the word has lost all but its symbolic meaning. Heaven is a spent

metaphor.