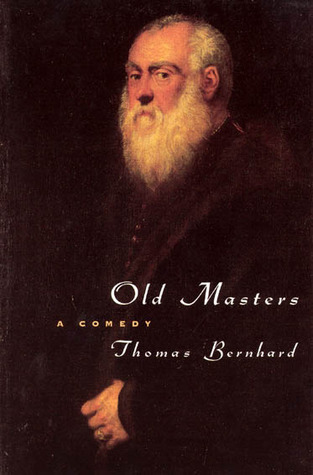

Old Masters

OLD MASTERS

A Comedy

Thomas Bernhard

Translated from the German

by Ewald Osers

The University of Chicago Press

The punishment matches the guilt: to be deprived

of

all appetite for life, to be brought to the

highest degree

of

weariness

of

life

KIERKEGAARD

Published by arrangement with Quartet Books Limited.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

Originally published in German as

Alte Meister

by

Suhrkamp Verlag,

Frankfurt am Main, © 1985 by

Suhrkamp Verlag.

Translation copyright © by

Ewald Osers

1989

Originally published 1989

University of Chicago Press edition 1992

Printed in the United States of America

99 98 97 96 95 94 93 92 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 0-226-04391-6

(pbk.)

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication

Data

Bernhard,

Thomas.

[Alte Meister.

English]

Old masters : a comedy / Thomas

Bernhard

;

translated from the German

by

Ewald Osers.

p. cm.

— (Phoenix fiction)

Translation of:

Alte Meister.

I. Title. II. Series.

PT2662.E7A7513

1992

833'.914

—

dc20

92-18986

CIP

∞

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the

American National Standard for Information

Sciences--Permanence

of Paper

for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984

Although I had arranged to meet Reger at the

Kunsthistorisches

Museum

at half-past eleven, I arrived at the agreed spot at half-past ten in order, as I had for some time decided to do, to observe him, for once, from the most ideal angle possible and undisturbed, Atzbacher writes. As he had his morning spot in the so-called Bordone Room, facing Tintoretto's

WhiteBearded

Man,

on the velvet-covered settee on which yesterday, after an explanation of the so-called

Tempest Sonata,

he continued his lecture to me on the

Art

of

the Fugue,

from

before

Bach to

after

Schumann, as he put it, and yet was in the mood to talk rather more about Mozart and not about Bach, I had to take up position in the so-called Sebastiano Room; I was compelled therefore, entirely against my inclination, to submit to Titian in order to be able to observe Reger in front of Tintoretto's

White-Bearded

Man,

moreover standing, which was no disadvantage because I prefer standing to sitting, especially when engaged in observing people, and I have all my life been a better observer standing up than sitting down, and as, looking from the Sebastiano Room into the Bordone Room, I eventually, by focusing as hard as I could, was able to see Reger completely in profile, not even impaired by the back-rest of the settee, Reger who, no doubt badly affected by the sudden change in the weather during the preceding night, kept his black hat on his head the whole time, so as I was therefore able to see the whole left side of Reger exposed to me, my plan to observe Reger undisturbed for once had succeeded. As Reger (in an overcoat), supporting himself on a stick wedged between his knees, was totally absorbed in viewing the

White-Bearded

Man

I had not the least fear, while observing Reger, of being discovered by him. The attendant Irrsigler (Jenö!), with whom Reger is linked by an acquaintanceship of more than thirty years and with whom I myself have always to this day had good relations (also for over twenty years), had been warned by a hand signal on my part that for once I wished to observe Reger undisturbed, and whenever Irrsigler appeared, with clockwork regularity, he acted as if I were not there at all, just as he acted as if Reger were not there at all, while he, Irrsigler, discharging his duty, subjected the visitors to the gallery, who, incomprehensibly on this free-admission Saturday, were not numerous, to his customary (for anyone who did not know him) disagreeable scrutiny. Irrsigler has that irritating stare which museum attendants employ in order to intimidate the visitors who, as is well known, are endowed with all kinds of bad behaviour; his manner of abruptly and utterly soundlessly appearing round the corner of whatever room in order to inspect it is indeed repulsive to anyone who does not know him; in his grey uniform, badly cut and yet intended for eternity, held together by large black buttons and hanging on his meagre body as if from a coat rack, and with his peaked cap tailored from the same grey cloth, he is more reminiscent of a warder in one of our penal institutions than of a stateemployed guardian of works of art. Ever since I have known him Irrsigler has always been as pale as he now is, even though he is not sick, and Reger has for decades described him as

a state corpse on duty at the

Kunsthistorisches

Museum for over thirty-six years.

Reger, who has been coming to the Kunsthistorisches Museum for over thirty-six years, has known Irrsigler from the first day of his employment and maintains an entirely amicable relationship with him.

It only required a very small bribe to secure the settee in the

Bordone

Room forever,

Reger told me some years ago. Reger entered into a relationship with Irrsigler which has become a habit for both of them for over thirty years. Whenever Reger, as happens not infrequently, wishes to be alone in his contemplation of Tintoretto's

White-Bearded Man,

Irrsigler quite simply blocks the Bordone Room to visitors, he quite simply places himself in the doorway and lets no one pass. Reger need only give a hand signal and Irrsigler blocks the Bordone Room, indeed he does not shrink from pushing any visitors already in the Bordone Room out of the Bordone Room, because that is Reger's wish. Irrsigler finished an apprenticeship as a carpenter in Bruck-on-Leitha but gave up carpentry even

before

qualifying as an assistant carpenter in order to become a policeman. The police, however, turned Irrsigler down because of his

physical weakness.

An uncle, a brother of his mother, who had been an attendant at the Kunsthistorisches Museum since nineteen twenty-four, got him his post at the Kunsthistorisches Museum,

the most underpaid but the most secure,

as Irrsigler says. Anyway, Irrsigler had only wanted to join the police because the career of a policeman would, as he believed, solve his clothing problem. To slip all one's life into the same clothes without even having to pay for those clothes out of his own pocket because the state provided them, appeared to him ideal, and his uncle, who got him into the Kunsthistorisches Museum, had thought the same way, and anyway there was no difference in this respect between being employed by the police and being employed by the Kunsthistorisches Museum, admittedly the police paid more and the Kunsthistorisches Museum less, but then service in the Kunsthistorisches Museum could not be compared with service in the police, he, Irrsigler, could not imagine a

more responsible but at the same time easier service

than in the Kunsthistorisches Museum. In the police, Irrsigler said, a man served day after day in danger of his life; not so if he served at the Kunsthistorisches Museum. As for the monotony of his occupation there was no need to worry, he loved that monotony. Each day he would cover some forty to fifty kilometres, which was more beneficial to his health than, for instance, service in the police, where the main part of the job was sitting on a hard office chair, life-long. He would

rather shadow visitors to the museum than normal people,

for visitors to the museum were at any rate

superior people with an understanding of art.

In the course of time he had, he said, acquired such an understanding of art that he would be capable at any time of guiding a conducted tour through the Kunsthistorisches Museum, or certainly through the picture gallery, but he could do without that. Anyway, people do not take in what is said to them, he says.

For decades the museum guides have always been saying the same thing, and of course a great deal of nonsense, as

Herr Reger

says,

Irrsigler says to me.

The art historians only swamp the visitors with their twaddle,

says Irrsigler, who has, over the years, appropriated verbatim many, if not all, of Reger's sentences. Irrsigler is Reger's mouthpiece, nearly everything that Irrsigler says has been said by Reger, for over thirty years Irrsigler has been saying what Reger has said. If I listen attentively I can hear Reger speak through Irrsigler.

If we listen to the guides we only ever hear that art twaddle which gets on our nerves, the unbearable art twaddle of the art historians,

says Irrsigler, because Reger says so frequently.

All these paintings are magnificent, but not a single one is perfect,

Irrsigler says after Reger. People only go to the museum because they have been told that a cultured person must go there, and not out of interest, people are not interested in art, at any rate ninety-nine per cent of humanity has no interest whatever in art, as Irrsigler says, quoting Reger word for word. He, Irrsigler, had had a difficult childhood, a mother suffering from cancer and dying when she was only forty-six, and a womanizing and perpetually drunk father. And

Bruck-on-Leitha,

moreover, is such an ugly place, as are most of the places in

Burgenland.

Anyone who can do so leaves the Burgenland, Irrsigler says, but most of them cannot, they are sentenced to Burgenland for life, which is at least as terrible as imprisonment for life at Stein-on-Danube. The Burgenlanders are convicts, says Irrsigler, their native land is a penal institution. They try to make themselves believe that they have a beautiful homeland, but in reality Burgenland is boring and ugly. In winter the Burgenlanders choke in snow and in summer they are eaten alive by mosquitoes. And in spring and autumn the Burgenlanders only wallow in their own filth. In the whole of Europe there is no poorer and no filthier region, Irrsigler says. The Viennese are forever persuading the Burgenlanders that Burgenland is a beautiful province, because the Viennese are in love with Burgenland filth and with Burgenland dimwittedness because they regard this Burgenland filth and this Burgenland dim-wittedness

as romantic,

because in their Viennese way they are perverse. Anyway,

apart from

Herr Haydn,

as

Herr Reger

says,

Burgenland has produced nothing, Irrsigler says. I come from Burgenland means nothing other than I come from Austria's penal institution. Or from Austria's mental institution, Irrsigler says.

The

Burgenlanders

go to Vienna as

i

f to church,

he says. A Burgenlander's fondest wish is to join the Vienna police, he said a few days ago, I failed to do so because I was too weak, because of

physical weakness.

Anyway I am an attendant at the Kunsthistorisches Museum and just as much a public servant. In the evening, after six, I do not lock up any criminals but works of art, I lock up Rubens and Bellotto. His uncle, who had entered the services of the Kunsthistorisches Museum immediately after the First World War, had been envied by everyone in the family. Whenever they had visited him at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, once in every few years, on free-admission Saturdays or Sundays, they had always followed him

totally intimidated through the rooms with the great masters

and had not ceased to admire

his uniform.

Naturally his uncle had soon become Senior Attendant and had worn a small brass star on his uniform lapel, Irrsigler said. With all that reverence and admiration they had, as he was leading them through the rooms, understood nothing of what he said to them. There would have been no point in explaining Veronese to them, Irrsigler said a few days ago. My sister's children, Irrsigler said, admired my soft shoes, my sister stopped in front of the Reni, in front of that most tasteless of all painters exhibited here. Reger hates Reni, therefore Irrsigler hates Reni too. Irrsigler has achieved a high degree of mastery in appropriating Reger's statements, indeed he now utters them almost perfectly in Reger's characteristic tone. My sister visits

me and not the museum,

Irrsigler said. My sister does not care for art at all. But her children are amazed at everything they see when I guide them through the rooms. They stop in front of the Velazquez and refuse to move away from it, Irrsigler said. Herr Reger once invited me and my family to the Prater, Irrsigler said,

the generous

Herr Reger,

on a Sunday evening. When his wife was still alive,

Irrsigler said. I stood there, watching Reger, who was still

engrossed,

as they say, in contemplating Tintoretto's

White-Bearded

Man,

and simultaneously saw Irrsigler, who was not in the Bordone Room, recounting to me chunks of his life story, i.e. the images with Irrsigler from the past week at the same time as Reger, who was sitting on the velvet settee, and naturally, had not yet noticed me. Irrsigler had said that even as a small child his fondest wish had been to join the Vienna police, to be a policeman. He had never wanted to have any other profession. And when, at the time he was twentythree, they had confirmed

physical weakness

in him at the Rossau barracks, a

world had collapsed for

him. In his state of extreme hopelessness, however, his uncle had got him an attendant's position at the Kunsthistorisches Museum. He had come to Vienna with nothing but a small scuffed portmanteau, to his uncle's flat, who had let him stay with him for four weeks, after which he, Irrsigler, had moved as a lodger to the Mölkerbastei. In that rented room he had lived for twelve years. During those first few years he had seen nothing of Vienna at all, he had gone to the Kunsthistorisches Museum in the early morning, towards seven, and had returned home in the evening, after six, his midday meal all those years had invariably consisted of a slice of bread with salami or with cheese, consumed with a glass of water from the tap in a small dressing room behind the public cloakroom. Burgenlanders are the most undemanding of people, I have myself worked with Burgenlanders at various building sites in my youth and lived with Burgenlanders in various builders' hutments, and I know how undemanding these Burgenlanders are, they only need the most indispensable things and actually manage to save some eighty per cent or even more of their wages by the end of the month. As I was scrutinizing Irrsigler and actually observing him intently, as I had never observed him before, I could see Irrsigler standing with me in the Battoni Room the previous week and me listening to him. The husband of one of his great-grandmothers had come from the Tyrol, hence the name Irrsigler. He had had two sisters, the younger one, as late as the sixties, had emigrated to America with a hairdresser's assistant from Mattersburg and had died there of homesickness, at the age of thirty-five. He had three brothers, all of them living in Burgenland as casual labourers. Two of them, like himself, had come to Vienna to join the police but had not been accepted. And for the museum service, he said,

a certain intelligence was absolutely necessary.

He had learned a lot from Reger. There were people who said Reger was mad because only a madman could for decades go every other day except Monday to the picture gallery of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, but he did not believe that.