Old Town (2 page)

1957 – Anti-Rightist Movement quells all criticism of party in society at large and strives to purge society of “anti-revolutionary” elements.

1958 – “Great Leap Forward,” the name given to the Second Five-Year Plan, aims at rapid industrialization and development of agricultural sector.

1958–1961 – Years of widespread famine result from major policy errors underlying Great Leap Forward, exacerbated by natural disasters.

1966–1976 – Period of Maoist “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution,” also known in China as “Ten Years of Catastrophe.” While the Revolution’s aims are complex and contradictory, many of Chairman Mao’s ideological rivals and personal enemies are eliminated. Precipitous rise to power of Jiang Qing, Mao’s final wife and the leader of the “Gang of Four” radical ideologues.

1968 – Mao orders “Down to the Countryside” campaign for urban youth who make up the increasingly violent and fractious Red Guards and nonstudent “rebel factions.”

1971 – Death of Marshall Lin Biao, Chairman Mao’s appointed successor, amid rumors of coup and countercoup plots.

1976 – Death of Chairman Mao Zedong, downfall of Jiang Qing and rest of the “Gang of Four.” Deng Xiaoping commences rise to paramount power.

1977–1979 – “Beijing Spring” and “Democracy Wall” period. Deng Xiaoping repudiates excesses of Cultural Revolution period and effectively ends exclusionary class background system. “Democracy Wall” closed down when demands for greater democracy in China grow strident.

1980–1981 – Deng appoints Zhao Ziyang as prime minister and Hu Yaobang as party chairman. China’s “Opening Up” to the world proceeds along with far-reaching economic and political reforms.

I shall open my mouth and speak in allegory,

the mystery of bygone days shall I tell,

Of what I have heard and know,

and of what our forefathers have told us,

These we shall not hide from their children and grandchildren,

So future generations shall be told of Yaweh’s goodness and might,

and of his marvelous deeds.

—Psalm 78

HAPTER

O

NE

– A F

ORGOTTEN

O

LD

T

OWN

1.

R

AIN…PITTERING, SPLASHING…THE ETERNAL

rainy skies of Old Town. I am sitting at that ancient Eight Immortals table in our parlor, staring blankly, my chin in my hands. As I look out at the drenched streets of the West Gate neighborhood, at the dripping eaves of the houses and the trickling branches of the trees, I think of the world beyond this old southern town—of the world I long for. And I am thinking,

What am I doing here in Old Town? What am I doing living in this house?

This is something I can never figure out. I long to leave Old Town. It’s like being homesick for somewhere else, and I’ve often felt the worst kind of sadness sitting in this house at West Gate. I’m like a traveler in exile who has no idea of where she will ever find a home.

Into this drenched and soaking street scene suddenly barges a familiar shape—Chaofan! He stops abruptly and peers inside. He clearly sees me. But his look is so strange. He doesn’t know me. He has never known me. He’s just happened to bump into a silly girl staring blankly, chin propped up in her hands. He lets his momentary curiosity pass, and is on his way again.

This picture doesn’t feel very logical. It is like some badly edited scene in a movie.

Chaofan, why don’t you recognize me?

I want to shout to him, but the sounds just won’t come out. When I opened my eyes, I was in a moving railway car. The wheels rolled along, cling-

cleng

-cling-

cleng.

The coach swayed and rocked and the green window curtain rested on my shoulder. I remained in a kind of trance, thinking of Chaofan on the rain-soaked streets of Old Town, but whether I was still dreaming or not, I couldn’t tell.

The young man who had been sitting at my side returned to his seat, holding a glass brimming with steaming tea. He was with two others just like him, who sat directly across from me and chatted away in the Old Town dialect as if they hadn’t a care in the world. Something about making some money up north by reselling dark glasses and fake name-brand watches smuggled in from the coast. In the late 1970s and the early 1980s, the term for smuggling, “running private-channel goods,” was relatively new in China. My first impressions of this sort of thing had been positive. Private-channel goods were the genuine article at a fair price, and people who ran such items were unusually resourceful. Right! They even asked me if I wanted to buy a Rolex. I had no idea what a Rolex was. They said it was Switzerland’s very best wristwatch and had been imported “privately” from Taiwan. I knew only that Titoni watches were from Switzerland and my mother wore one. I had heard that my grandfather, her father, gave it to her as part of her dowry. The watch core was inlaid with seventeen diamonds and I used to wish it would break so that I could get those seventeen diamonds, though I had never in my life seen a diamond. The three “private-channel elements” spoke to me in Mandarin, taking me for a “northern guy.”

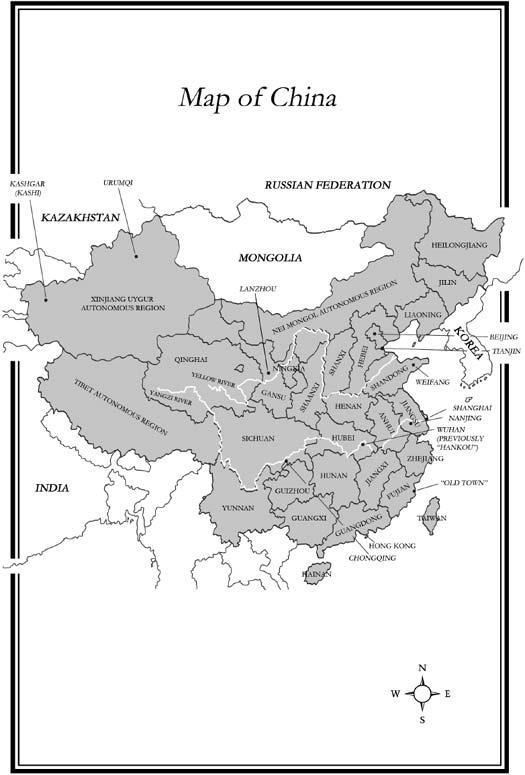

Old Town people thought I grew up looking more and more northern. I had a round face, fair with the slightest tinge of red, and I was taller than most of the girls in Old Town. Grandma looked at me anxiously once and said, “You mustn’t grow any more. If you get any bigger, you might have a hard time getting married.” And the blood of northerners really

does

course through my veins. I was born in the little town of Kashgar, far away on the Xinjiang border. The father I had never seen was a northern guy. From his photograph, I knew I looked like him. I looked like him a lot.

The train suddenly slowed and the fellow holding the glass of tea was caught off balance. As he staggered, boiling tea poured onto my leg and I yelled out in pain. The three young men said, “Sorry,” all together in their Old Town-accented Mandarin.

My head cleared up completely under all this pain. But my hand didn’t reach down to soothe my scalded thigh; instead, it automatically felt for the envelope hidden at my breast. In that envelope was my university admission notice, while one hundred and fifty

yuan

were safely tucked in a pocket in my underwear. I finally believed this was no dream. I really was on a journey and leaving Old Town far behind.

Moving aside the curtain to look out at the gently swaying and pretty countryside, I breathed out deeply, as if letting go of a heavy burden. But immediately doubts and hesitation again weighed me down. I thought of Chaofan. The year before he had tested successfully for entry into the Beijing Institute of Art, and so Beijing became the realm of my dreams and reveries. Before setting out, I sent him a telegram. Our year of separation has made my love for him all the more incurable.

That’s how I left Old Town.

In more than twenty years, I’ve returned only a few times. My grandparents, Mother’s parents, were no longer living, and the old West Gate home of my childhood has been razed. Old Town and all of China’s other places are now undergoing similarly drastic cosmetic surgery. Work sites for this disembowelment are everywhere. Even though from my earliest years I had longed to leave Old Town, every time I realized my childhood home and my grandpa and grandma were lost to me forever, that uprooted and forsaken feeling would hit all over again. Maybe I dreaded returning home because of the nostalgic feelings I still held on to.

I kept on going. I went to the other side of the ocean, to a little place called Lompoc, California. The pressures of just staying alive there kept me from thinking too much of where I had come from or where I was going. I did not even have the time to see much of the sunshine and beaches only a stone’s throw away. I almost forgot Old Town. I had come from Beijing and everyone in Lompoc took me for a Beijinger.

Within a brief few months, I had worked in every Chinese restaurant in Lompoc. When I was looking for my first job, I lied about “having experience.” That evening the boss “sautéed my cuttlefish,” that is, he fired me. After repeated cuttlefish sautés, though, I could justifiably say I was experienced.

One day, before yet another of those restaurants was opening for business, another girl and I were setting the tables, folding the cloth napkins into patterns and placing them in glasses. I was just taking some glasses from the pushcart, when suddenly, from behind me, came a loud voice:

“Reporter!”

Working here were also PhDs, medical doctors, professors, and actors. Before hiring staff, the boss would ask each person his or her original profession back in China, and then these became our names. I guessed that he got a special thrill ordering us around, for he hadn’t had much of an education himself. “What’s the big deal about being educated? Don’t you still depend on me to keep you going?” He talked like that.

What had I done wrong? Was the boss about to sauté some cuttlefish?

Inside, I felt inches tall.

The boss’s big fat head stuck out from behind the counter, both eyes looking as if they were about to burst, “You’re slacking off!”

Slacking off? How?

Ever since I started working in restaurants, I had forced myself to quit drinking tea all the time because it kept making me run to the toilet. I now chewed dry tea leaves to keep myself energized.

I just stood there, gaping. I was holding seven or eight glasses. Next to me stood Violinist—the boss called her Performer—who quietly said, “You’re not supposed to stick your fingers inside the glasses.”

Right then the boss roared out, “Trying to wreck my business, eh?”

Performer relieved me of the glasses I was holding and wiped them clean, one by one, with a cloth napkin. Actually, the napkin was a whole lot dirtier than my hands.

I nervously stole a glance at the boss, trying to figure out whether it would be sautéed cuttlefish time again…

I was really pathetic. I couldn’t help asking myself why I had to travel so far across the ocean just to end up here. When I was little, the only thing I wanted was to leave Old Town. I felt that I would find a real home somewhere far, far away from my old one at West Gate. But later, in Beijing when I set up on my own, I felt it still wasn’t home. I threw away my job and dumped my daughter to go chasing off to America after Chaofan. Where else could I migrate to in this world? Where would I find a real home?

Lompoc’s population was small but its vein of religious sentiment ran very rich and deep. There were always people knocking on doors and preaching. Chaofan would get really irritated at this and figure out ways to shut up their preaching. To the Buddhists he would say, “I’m a Christian,” and to the Christians he would say, “I’m a Buddhist.” If the believer persisted, Chaofan would then sternly warn them: “America’s a free country and you’re interfering with my freedom of belief.” This always did the trick. Privately, Chaofan and I were both proud to be atheists. For him, “religion” was another word for ignorance and foolishness. I myself wasn’t quite as extreme. I believed religion made people good. Perhaps someday later on, when I had a career that guaranteed me food and clothing, I would think about being a good person, but at the moment, I had too many problems and worries. Where and when would I have leisure enough to sing songs of praise for a god who didn’t exist anyway?

Several days later, I found in a Chinese-language tabloid a job that I

was

uniquely qualified for. The only requirement was “fluency in the South China Old Town dialect.” When my eyes latched onto these words, it was as if a thunderclap from heaven had exploded right over my head alone, and I reentered a history that I had severed myself from so completely and so long ago. Old Town, soggy Old Town, now reappeared fresh and alive in my memory.

Old Town, root of my existence, how could I ever have forgotten you?

Lucy, my employer, a fair-complexioned woman with black hair and dark eyes, totally surprised me when she came out with a few simple words of Old Town dialect. My job was to look after her mother, a woman who had been born in the south of China, in Old Town, actually. Lucy’s now-deceased father had once worked in China as a young man and had married a Chinese woman. Her mother, now nearly eighty years old, had been stricken the year before with some serious illness and was suddenly unable to understand English, or even Mandarin. All she could do was speak Old Town dialect in a squeaky,

yi-yi-ya-ya

way. Baffled, Lucy shook her head and said, “Before, my mother could read the Bible in English. When she was young, she and my father went all around preaching the Word, and she spoke very proper Mandarin.”

The name of this peculiar old lady was Helen. Every day when I wheeled her out to take some sun and the neighbors all greeted her, she made no response whatsoever. Lompoc was quite small and the people there all knew each other, but she always asked me, “When did all these ‘outlandish folk’ (Old Town dialect for ‘foreigners’) get here?” She thought Lompoc was Old Town. And it’s true, every time the skies grew overcast and it started to drizzle, the soaked streets exuded that feeling only Old Town had. I didn’t ask her what her Chinese name was and just called her “Ah Ma” (“Granny” in our dialect). She paid no attention, but I persisted in calling her that. Ah Ma’s three children lived and worked in other parts of the country. Lucy, the youngest, lived the closest, in Los Angeles, and going back and forth by car would take her about four hours. As far as Ah Ma was concerned, her children were of no great importance and she actually didn’t recognize them. Her frail old body was in Lompoc, but her spirit had already crossed time and space to return to Old Town, back to her early childhood days. She called me Big Sister, Second Sister, and Nursey, or Flower, or Elegant. In Old Town, on every street, there were many girls named Flower or Elegant. I felt for her. I often couldn’t help having a bout of self-pity out of kindred feelings. “A rabbit dies and even the fox feels sad,” as we like to say. Wasn’t Helen’s

today

a preview of my

tomorrow

? I saw myself sitting like her in a wheelchair, unable to speak English, unable to speak Mandarin, and using the Old Town dialect that nobody could make anything out of, right up to my death of old age in a strange land.

Helen had her lucid moments, though. Every day at nine o’clock in the morning, she would ask very clear-headedly for me to read the Bible to her and I would do so in the Old Town dialect. After hearing a small portion, she would stop me and say, “Let’s share this part of the text.” She related very well to the lives of the twelve apostles, as if they had been her old acquaintances. But then, closing the Bible, she would revert to total incoherence. As I read the Bible to her, I would try to awaken her memories. “Ah Ma, when did you come to America?” “America?” She would squint and say, “I’ve heard of it. Never went there, though.” “Ah Ma, who gave you your English name Helen?” “Helen? Such an interesting name—is it yours?” If I kept on with these kinds of questions, she would get irritated and say, “You haven’t finished reading this part of the text yet.”