Ole Doc Methuselah

Also by

L. Ron Hubbard

Buckskin Brigades

The Conquest of Space

The Dangerous Dimension

Death's Deputy

The End is Not Yet

Fear

Final Blackout

The Kilkenny Cats

The Mission Earth Dekalogy*

Volume 1: The Invaders Plan

Volume 2: Black Genesis

Volume 3: The Enemy Within

Volume 4: An Alien Affair

Volume 5: Fortune of Fear

Volume 6: Death Quest

Volume 7: Voyage of Vengeance

Volume 8: Disaster

Volume 9: Villainy Victorious

Volume 10: The Doomed Planet

Ole Doc Methuselah

Slaves of Sleep & The Masters of Sleep

To the Stars

Triton

Typewriter in the Sky

The Ultimate Adventure

Â

* Dekalogyâa group of ten volumes

Â

For more information on L. Ron Hubbard and

his many works of fiction visit

www.GalaxyPress.com

.

Â

Galaxy Press

7051 Hollywood Boulevard

Los Angeles, CA

90028

OLE DOC METHUSELAH

©1992 L. Ron Hubbard Library. All Rights

Reserved.

Any unauthorized

copying, translation, duplication, importation or distribution, in whole or in

part, by any means, including electronic copying, storage or transmission, is a

violation of applicable laws.

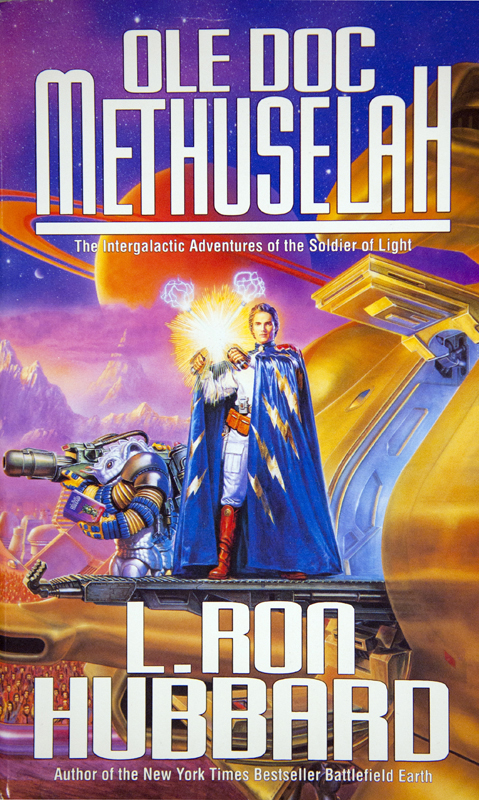

Cover Art: Gerry Grace

Cover artwork: © 1992 L. Ron Hubbard

Library. All Rights Reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-59212-599-9

Introduction

It was the autumn of 1947âthe tenth year of a golden age for John W. Campbell's

Astounding Science Fiction,

the

magazine that had reshaped and redefined science fiction into its modern form.

Campbell, coming to the editorship of

Astounding

at the age of 27 in

October, 1937, had tossed out within a year or two most of the old-guard

writers who had dominated the magazine, and had brought in a crowd of bright

and talented newcomers: such people as Robert A. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, L. Ron

Hubbard, A.E. van Vogt, L. Sprague de Camp, Theodore Sturgeon, Fritz Leiber,

Lester del Rey. Theyâand a few veterans like Jack Williamson and Clifford D.

Simakâwrote a revolutionary new kind of science fiction for Campbell, brisk and

crisp of style, fresh and lively and often irreverent in matters of theme, plot

and characterization. The readers loved it.

Astounding

was the place

where all the best stories wereâmany of them now classics, which have stayed in

print for fifty yearsâand both the magazine and its larger-than-life editor

were regarded with awe and reverence by its readership and by most of its

writers as well.

Hubbardâwhose famous writing career had

begun in the early 1930's in such wild-and-wooly pulps as

Thrilling

Adventures, Phantom Detective, Cowboy Stories,

and

Top Notch,

and

the more prestigious magazines as

Argosy, Adventure,

Western Stories, Popular Detective

and

Five Novels

Monthly,

had been especially commissioned by

publishers Street & Smith to write for

Astounding

magazine's editor

John W. Campbell Jr. in 1938. At 27, just a few months younger than Campbell,

he was already the author of millions of published words of fiction, and

Campbell wanted him for his knack of fast-paced story-telling and his bold

ideas. Soon Hubbard was a top figure in the

Astounding

of the 1940's and

in its short-lived but distinguished fantasy companion,

Unknown,

with

such Hubbard stories and novels as “The Tramp” (1938), “Slaves of Sleep”

(1939), “Typewriter in the Sky” (1940), “Final Blackout” (1940), “Fear” (1940),

“The Case of The Friendly Corpse” (1941) and “The Invaders” (1942). But then

Hubbard too went off to military service, and his contributions to Campbell's

magazines ceased for five years.

The extent of Hubbard's popularity among

the readers of

Astounding

and

Unknown

in the first few years of

Campbell's Golden Age was enormous. No better proof of that can be provided

than a letter from a young reader that was published in the April, 1940 issue

of

Unknown,

listing his ten favorite stories of 1939. Three of themâ“The

Ultimate Adventure,” “Ghoul” and “Slaves of Sleep”âwere by L. Ron Hubbard. (The

young reader's name was Isaac Asimov, who would soon be one of Campbell's

Golden Age stalwarts himself.) So when Hubbard finally returned to the pages

of

Astounding

in the August, 1947 issue with a grim three-part novel of the

postwar atomic-age world, “The End Is Not Yet,” reader response was

enthusiastic.

But there was more to Hubbard's return than

the readers of that season suspected. Even while “The End Is Not Yet” was still

being serialized, Campbell began to offer them the start of another major

Hubbard enterpriseâthe first of a series of high-spirited space adventures

under the pseudonym of Rene Lafayette. Entitled “Ole Doc Methuselah,” it

appearedâwithout any of Campbell's customary advance build-upâas the lead story

of the October, 1947

Astounding,

which also carried the final segment of

the Hubbard novel.

The “Lafayette” pseudonym was not new.

Hubbard had used it at least once before, in the April, 1940 issue of

Unknown,

on a short novel called “The Indigestible Triton.” The name was simply a

variation on Hubbard's ownâ(the “L.” in “L. Ron Hubbard” stands for

“Lafayette”)âand almost certainly was used on “The Indigestible Triton” because

of the extraordinary number of Hubbard stories that had been appearing in

Campbell's magazines in 1940: editors often get uneasy when one writer appears

to be too prolific. Very likely the pseudonym was revived for “Ole Doc

Methuselah” for much the same reason. With “The End Is Not Yet” already running

in

Astounding,

Campbell would not have wanted to use the same author's

byline twice in the same issue.

“Ole Doc Methuselah”âthe first of the seven

galactic exploits in the book you are now holdingâis an entertaining adventure

hearkening back to Hubbard's other genre writingâperhaps reminiscent of one of

his classic westerns: The glamorous, mysterious young doctor and his comic but

highly effective sidekick come riding into town to set things straight. The bad

guys have set up a phony land-development scheme, saying that the railway will

be coming through soon and everybody in town will get rich. But of course it's

a swindle, and it will be up to the young doctor and his buddy to defeat the

villains and set everything to rights.

The readers loved it. “The Analytical

Laboratory,” the reader-response poll that Campbell published every month,

reported in the January, 1948

Astounding

that it had been the most

popular story in the October issue. (The conclusion of Hubbard's “The End Is

Not Yet” serial finished in second place.) Campbell himself noted, in

commenting on the results, that he personally would classify the story “as fun

rather than cerebral science fictionâand its position [in the poll] testifies

that any type of science-fiction, well done, will take a first place!”

Cartier's lively,

boldly outlined drawings provided images of Doc and his alien slave Hippocrates as definitive

as those that Tenniel did for Lewis Carroll's “Alice in Wonderland,” and gave

the reader a cue not to take the story

too

seriously. Everyone knew

right away that Ole Doc was a high-spirited rompâCampbell and Hubbard in an

unbuttoned mood, sharing some fun with their readers for some great

entertainment.

Cartier, who illustrated more stories by

Hubbard than anyone else, has written fondly of his association with Hubbard's

work and with “Ole Doc Methuselah“ in particular. “Illustrating Ron's tales was

a welcome assignment,” he said, “because they always contained scenes or

incidents I found easy to picture. With some writers' work I puzzled for hours

on what to draw and I sometimes had to contact Campbell for an idea. That never

happened with a Hubbard story. His plots allowed my imagination to run wild and

the ideas for my illustrations would quickly come to mind. . . . It was Ole

Doc's adventures that many people, including myself, recall most fondly.

Readers like my depiction of Hippocrates and I always enjoyed drawing the

little, anten-naed, four-armed creature. Oddly enough, in 1952 my wife, Gina,

found a large five-legged frog in our yard. . . . Needless to say, the mutant

frog was instantly dubbed Hippocrates or Pocrates, for short. He resided with

honor in a garden pool and was featured in many local newspaper articles. The

frog's existence was as if Ron's writings and my illustrations had come to life

to prove that science fiction's imaginative ideas are quite within the realm of

possibility.”

A month after his debut, Ole Doc Methuselah

returned, with “The Expensive Slaves“ in the November, 1947 issue. Again praised

in the letter column of “The Analytical Laboratory,” there was no question that

the series had been successfully launched, and the readers of the eraâI was

one-looked forward eagerly to the next episode.

They didn't have long to wait. Doc was back

in the March, 1948 issue with “Her Majesty's Aberration.” The fourth in the

seriesâ“The Great Air Monopoly”âappeared in September, 1948. The April, 1949

issue brought “Plague,” a long lead story which gave the series its first

display on

Astounding's

cover. Two months later came “A Sound

Investment.” (Campbell, announcing that story in the previous issue, commented,

“This is one series in which the continuing hero is frankly and directly

labeled as being deathless, incidentally; you won't often find an author

admitting that.” January, 1950 saw publication of “Ole Mother Methuselah,” the

seventh of the Ole Doc Methuselah series.

And there the series ended. Hubbard had

other projects of a whole new scope. In the May, 1950

Astounding

Campbell

published Hubbard's non-fiction essay, “Dianetics, the Evolution of a Science,”

and shortly afterward came Hubbard's book,

Dianetics, The Modern Science of

Mental Health.

It would be many years before Hubbard would write science

fiction again.

Ole Doc Methuselahâthe seven stories

collected here is Hubbard's most genial book. We see amiably miraculous events

described in broad, vigorous strokes. Ole Doc, in three hours of deft plastic

surgery, undoes an entrenched tyranny and restores an entire world's social

balance. Space pirates, land barons, vindictive Graustarkian queens, sinister

magnates who make air a marketable commodityânothing is too wild, too

implausible, for the protean Hubbard. The immortal (but human and sometimes

fallible) superhero and his wry, nagging alien pal are plainly destined to

succeed in everything they attempt, and the key question is not

if

but

how

they will undo the villain and repair the damage that he has done.

That having been said, though, it would be

a mistake to minimize these seven stories as light literature turned out by a

great science-fiction writer in a casual mood. They have their roots in

pulp-magazine techniques, but so did nearly everything that Campbell published

in that era. In a time before network television and paperback books, the pulp

magazines were the primary source of entertainment for millions of readers, and

the best pulp writers were masters of the art of narrative.

The action in the Methuselah stories is

fast and flamboyant and the inventiveness breathless and hectic. The mind of a

shrewd and skilled storyteller can be observed at work on every page, and the

stories grow richer and deeper as the series progressesânote, particularly, the

touching moment in “The Great Air Monopoly” when Doc enters Hippocrates'

working quarters aboard their ship. (“A bowl of gooey gypsum and mustard, the

slave's favorite concoction for himself, stood half eaten on the sink, spoon

drifting minutely from an upright position to the edge of the bowl as the

neglected mixture hardened. A small, pink-bellied god grinned forlornly in a

niche, gazing at the half-finished page of a letter to some outlandish world. .

. . Ole Doc closed the galley softly as though he had been intruding on a

private life and stood outside, hand still on the latch. For a long, long time

he had never thought about it. But life without Hippocrates would be a

desperate hard thing to bear.”) And though a lot of Doc's medicinal techniques

look more like magic to us, I remind you of Arthur C. Clarke's famous dictum

that the farther we peer into the future, the more closely science will seem to

us to resemble magic. Ole Doc is nine hundred years oldâhe took his medical

degree from Johns Hopkins in 1946âand looks about twenty-five; but who is to

say that people now living will not survive to range the starways nine hundred

years from now? It may not be likely, but it's at least conceivableâand fun to

think about.

The stories are good-natured entertainment;

and they give us something to think about. As Alva Rogers pointed out

in A

Requiem for Astounding,

his classic history of John Campbell's great

magazine, “The âOle Doc Methuselah' stories were immensely enjoyable; there was

nothing pretentious about them, they were full of rousing action, colorful

characters, spiced with wit, and yet, underneath it all, had some serious

speculative ideas about one possible course organized medicine might take in

the future and a picture of medical advances that was very intriguing.” They

were well-loved stories in their day, rich with their sense of wonder; and here

they are again, to delight, amuse and amaze a new readership now.

â

Robert Silverberg

Award-winning

author, Robert Silverberg, has written over 100 books and numerous short

storiesâand is equally renowned as a top editor of science fiction anthologies.

â The Publisher