On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (13 page)

Read On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears Online

Authors: Stephen T. Asma

The stories of these creatures in Daniel and Revelation bring into relief a texture of monsterology that eventually comes to dominate the medieval religious mind. These monsters are symbols of prideful insurgency, and as such must be brought low and be damned by God’s overwhelming justice. They are symbols of what men will inevitably become, pawns in various regimes of torture, if they attempt to rule without the guidance and approval of Yahweh. In the Jewish tradition the monsters are incarnations of the inevitable political trouble that arises when gentiles impose upon the chosen people. In the prophecy traditions, monsters are not creatures of natural history but symbolic warnings of a horrifying life without the Abrahamic God (or, in the case of Christians, without his son). They are the symbols of both degenerate paganism and fallen “children of disobedience,” those who should know better but have given in to earthly temptation. In Old Testament beast narratives, such as the Book of Daniel, the reckoning is accomplished by Yahweh’s greater strength. But in Christian versions, such as in the Book of Revelation, the paradoxical ingredient of

the lamb’s blood (Christ’s sacrifice) is added as the ultimate weapon in the arsenal.

The “Beast” with seven cat-like heads, from the Book of Revelation. From Alixe Bovey,

Monsters and Grotesques in Medieval Manuscripts

(University of Toronto Press, 2002). Reprinted by kind permission of the British Library.

It may be worth mentioning that these prophetic books of the Bible have themselves been treated in some quarters as monstrous appendages on the sanctified scriptural corpus. In addition to the obvious recent history of suicidal apocalyptic groups such as the American Branch Davidians and the Ugandan Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God, one finds warnings about these prophetic scriptures in both Jewish and Christian theology. Maimonides (1138–1204), who is probably the most influential Jewish philosopher of the medieval period, argued that only fools try to calculate the actual end time. To attempt to prophesy a precise coming of the Messiah is a dangerous business, and an untutored public will be led astray by such pseudo theology. From the father of the Christian Reformation himself, Martin Luther

(1483–1546), we hear serious anxiety about allowing the flock to read the potentially dangerous Book of Revelation.

17

Dangerous or not (or perhaps

because

they were dangerous), these biblical monsters were like manna for the medieval imagination and served to simultaneously inspire wonder, provide metaphysical explanations of history, legitimize authority, and foster fear-based morality.

18

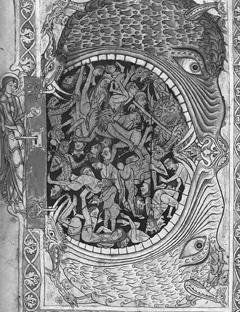

A medieval depiction of hell as a monstrous mouth. From Alixe Bovey,

Monsters and Grotesques in Medieval Manuscripts

(University of Toronto Press, 2002). Reprinted by kind permission of the British Library.

Throughout the medieval era, the scriptures and their subsequent interpretations and pictorial representations slowly build a new version of God. The monotheistic deity becomes the most fearful entity in the medieval imagination, partly because he’s capable of staggering violence, but also because he’s unknowable and infinitely powerful.

A race of biblical monsters that seem largely forgotten by the moderns but were a source of endless fascination for the medievals is the giants. Most of the speculation about giants stems from a passage in Genesis (6:1–4): “And after that [Noah becoming a father] men began to be multiplied upon the earth, and daughters were born to them, the sons of God seeing the daughters of men, that they were fair, took to themselves wives of all which they chose…. Now giants were upon the earth in those days. For after the sons of God went into the daughters of men, and they brought forth children, these are the mighty men of old, men of renown.” This passage, together with other cryptic references to giants (Numbers 13, Genesis 10:8–9, I Samuel 17:4–5), account for a popular theory about giants who roamed the earth prior to the Flood (most of whom died in the deluge, but some of whom may have lived on). Mainstream interpretations of the Genesis text follow the tradition laid down by Jerome and endorsed by Augustine, wherein the “sons of God” reference was interpreted as the offspring of Seth (Adam and Eve’s

other

son, besides Cain and Abel), and the “daughters of men” was read as the children of Cain.

19

But a radically different interpretation, further developed in the Book of Enoch,

20

seems to have predated, and even run parallel to, this now standard version.

In this alternative interpretation, the “sons of God” are taken to be angels who fall from grace because they have sex with beautiful human women (daughters of men). The Book of Enoch (7:2) says, “And when the angels, the sons of heaven, beheld them, they became enamored of them, saying to each other, Come, let us select for ourselves wives from the progeny of men, and let us beget children.” When these fallen angels, called Grigori or “the Watchers,” mated with mortal women, their offspring were giants called

nephilim

(from the Hebrew root

naphal

, “to fall”). The Grigori angels were punished for leaving their rightful place and cavorting with human women, and the giants were then destroyed by the Flood. In fact, the tradition that takes its lead from Enoch suggests that it’s the destruction of these mongrel giants, not man’s sinfulness, that explains God’s true motive for the Flood. In

chapter 7

Enoch explains that a kind of war had broken out between the giants and the humans. The giants had “consumed all the acquisitions of men. And when men could no longer sustain them, the giants turned against them and devoured mankind. And they began to sin against birds, and beasts, and reptiles, and fish, and to devour one another’s flesh, and drink the blood” (7:4–6). Finally, according to the story, the archangels went to God and asked him to resolve the bloodbath, and the cathartic Flood followed accordingly.

But the giants proved to be a wily breed and crop up from time to time in postdiluvian episodes, both canonical and apocryphal. The Venerable Bede (ca. 672–735), a Benedictine Church father, commented on the famous Genesis passage by saying, “It calls ‘giants’ men who were born with huge bodies, endowed with excessive power, such as, even after the Flood, we read that there were many in the times of Moses or David.”

21

For example, Nimrod, the grandson of Ham and instigator of the tower of Babel, was sometimes interpreted as a giant, and Goliath, whom David unexpectedly defeated with a slingshot, is described as the Philistine Giant. It’s worth quoting David’s battle speech to the incredulous Goliath: “This day, and the Lord will deliver thee into my hand, and I will slay thee, and take away thy head from thee: and I will give the carcasses of the army of the Philistines this day to the birds of the air, and to the beasts of the earth: that all the earth may know that there is a God in Israel” (I Samuel 17:46).

Like some other monsters in the Bible, giants symbolize hubris or arrogance. As such, they play the necessary foil to God’s righteous demonstrations of superior power. David is only a small boy relative to the giant Goliath, but his faith and courage create a conduit for Yahweh’s dispensation of justice. If you trust in the God of Abraham, even giants will fall.

Do Monsters Have Souls?

Monsters are not contrary to nature, because they come from divine will

.

ISIDORE DE SEVILLE

S

T. AUGUSTINE REJECTED

the Enoch-based interpretation of Genesis, that fallen angels (Grigori) mated with human women who gave birth to giants (nephilim).

1

But he did not reject this version on the grounds of some general prescientific skepticism. A careful reading shows that Augustine specifically objected to the fallen angels as begetters of giants. Humans of gigantic stature, Augustine observes, actually lived before, during, and after the episode of these fallen angels. By an impressive sleight of hermeneutical hand, he reads “angels” as “messengers” and then interprets these fallen men as just a different ethnic group (the sons of Seth) from the women (daughters of Cain), thereby tossing out the supernatural sex part of the story. The giants are preserved.

Augustine accepts the reality of individual giants and also the possibility of giant races in far-off lands. Moreover, he is convinced that the average pre-Flood humans were larger compared to contemporary humans:

But the large size of the primitive human body is often proved to the incredulous by the exposure of sepulchers, either through the wear of time or the violence of torrents or some accident, and in which bones of incredible size have been found or have rolled out. I myself, along with some others, saw on the shore at Utica a man’s molar tooth of such a size, that if it were cut down into teeth such as we have, a hundred, I fancy, could have

been made out of it. But that, I believe, belonged to some giant. For though the bodies of ordinary men were then larger than ours, the giants surpassed all in stature.

2

He cites a variety of ancient writers in defense of this general thesis, including Pliny the Younger, who concluded, “The older the world becomes, the smaller will be the bodies of men.” Which I suppose is a reasonable theory, albeit unfamiliar, when one is regularly digging larger bones out of the earth than one is encountering in the flesh.

The most marvelous of these giants were thought to be drowned in the Flood, of course, but Augustine reminds readers that giants of some sort will always be around. “Was there not,” he asks, “at Rome a few years ago … a woman, with her father and mother, who by her gigantic size overtopped all others? Surprising crowds from all quarters came to see her, and that which struck them most was the circumstance that neither of her parents were quite up to the tallest ordinary stature.”

3

Giants, in this sense, are part of the natural order of things, rare but unsurprising.

Archbishop Isidore of Seville (566–636), the learned author of the influential

Etymologiae

, reiterated Augustine’s views on giants, affirming their probable existence but denying their origin from angel-human coitus.

4

Like other issues in his encyclopedic summary of medieval knowledge, the word

gigantic

is dissected and given etymological analysis. Isidore’s analysis shows that the word is derived from the Greek

ge

(earth) and

genos

(kind, or clan), suggesting a race of powerful earth-born men (

terrigenas

).

According to Isidore, giants are just one of the various types of monsters (such as Cynocephali, Cyclopes, and Blemmyae) that exist at the margins of God’s creation.

5

But of course anomalies crop up inside the perimeter as well. In his chapter “De Portentis,” he corrects the pagan scholar Varro’s earlier claim that portentous births are “contrary to nature.” “But they are not,” Isidore counters, “contrary to nature, because they come by the divine will, since the will of the Creator is the nature of each thing that is created.”

6

Nature is a reflection of God, and like other reflections doesn’t contain anything beyond the original source. This intimate relationship, according to Isidore, leads pagans to sometimes refer to God as “Nature” and sometimes just “God.”

7

Being a good Christian during an era when intellectuals

were still extricating themselves from impressive Greek and Roman philosophy, Isidore sought to improve on pagan ideas of God. The idea that God created the world from nothing (

ex nihilo

) was a relatively recent idea, and it was considered incoherent by pagan intellectuals. Most ancient theories claimed instead that God was the force that gave shape and character to an otherwise unformed, shapeless matter.

8

By these ancient principles God did not

create

matter, which was thought to be contemporaneous with God, he only wrestled it into a coherent system. The explanatory advantage of this viewpoint with regard to monsters is that distorted and malformed beings could be seen as an unfortunate but necessary consequence of “difficult” matter. God tried to make this species perfect, but damnable matter proved recalcitrant during construction.