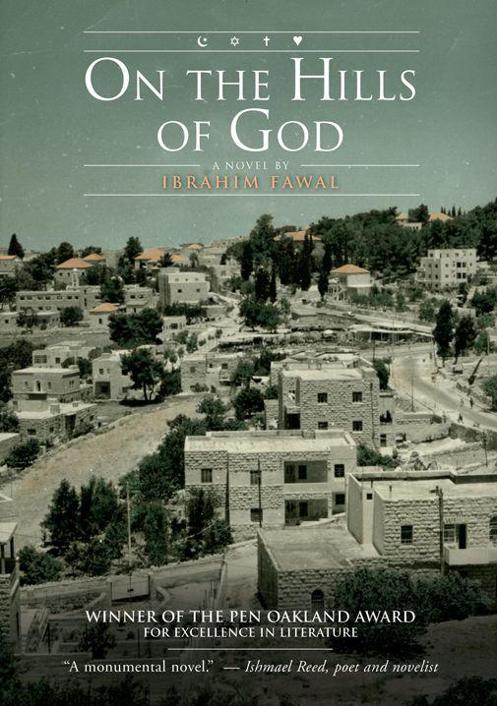

On the Hills of God (62 page)

Read On the Hills of God Online

Authors: Ibrahim Fawal

Tags: #Israel, #Israeli Palestinian relations, #coming of age, #On the Hills of God, #Palestine, #United Nations

“Wherever he is, he’s watching.”

“How much money do we have? At fifteen pounds a month for rent, it won’t last long. Not to mention the cost of food.”

“Here, count it.”

She handed him a small bundle she had lifted from inside her bodice. The bills were wrapped in a lacy handkerchief. He unwrapped them and began to count.

“Sixty, seventy, eighty, some people wish they have this much, ninety—”

“Masakeen,”

she said, pursing her lips. “What’s to become of them? How will they live? Thank God it’s summer. What will happen when winter comes? We’re all

masakeen.”

“—hundred and ninety . . . two hundred . . . two hundred and ten—”

“If we only had the jewelry.”

“—two hundred and forty, two hundred and fifty—”

“Yousif, what if they find it? Listen, son, what if they discover—?”

“Two hundred and eighty-five pounds. Plus the two in my pocket. And that’s it. That’s all we have to our names.”

He folded the money and handed it to her, but she motioned for him to keep it. Yousif caught the anxiety in her eyes. “What’s the matter?”

“On top of the jewelry—mine and Salwa’s—we had to leave them four hundred pounds. An icing on the cake.”

“To hell with it. Besides, there isn’t a chance they’ll find the jewelry.”

“Why?”

“Because it’s hidden.”

“What if they move the furniture around? What if they notice something peculiar about that one tile?”

“Not a chance.”

“I want to believe it, but I can’t.”

“Believe me, we’ll be back before Christmas,” he lied.

“Oh, sure.”

“You don’t think so?”

“Not for a moment. Every bone in my body tells me we’ll never see our home again.”

“Nonsense.”

“You wait and see. Everything we own is gone: the two homes, stock, clinic, savings, jewelry, the cash.”

Yousif was equally disturbed, but he wouldn’t admit it. Both lapsed into silence.

“Go to sleep, will you?”

“Listen to him. Go to sleep, he says. And if we’re lucky to go back, what will we find? Not a stick of furniture. Not a table, not a chair, not a dish, not a spoon.”

“Everything is replaceable,” Yousif said, rolling on the floor trying to sleep. “You yourself have said money and property aren’t everything. Remember?”

She remained upright in her chair. He closed his eyes, welcoming the feel of a soft breeze. He hoped it would lull his senses. His mother was probably right. Going home would be next to impossible. Thoughts of Basim, Salman, Uncle Boulus, and their families crossed his mind. Above all, he thought of Salwa. Where was she? Wherever she was, he hoped she had a bed. Was she sleeping on the floor like him? He wondered how long it would take to find her. What if it took him a week? Or a month? First thing in the morning, he would start looking for her.

He rolled to his side, his left leg straight and his right leg curled to his stomach. His cheek rested on the floor. The cool, smooth surface pleased him. But he could not sleep, could not succumb for an hour—if only for an hour—of rest. Reluctantly, he opened his right eye, peeking at his mother. She was still rigid in her place by the window, her hands clasped in her lap, and her eyes staring into the silvery night.

A wave of delicious sleep crept over him, and he yearned to float away with it. But it passed, leaving him awake. A bird fluttered in his head, dipping and flying over a vista of hurts and concerns. His nerves were too strained for him to concentrate. He wished the bird would disappear. Yet the bird hovered over the same wound, unmindful of his wishes.

The stillness of the night was deafening. It belied the havoc and turmoil Yousif felt inside. From the little he knew about the history of Zionism, this was not meant to be a temporary exile. The Zionist soldiers had not pushed them out at gunpoint to welcome them back before Christmas. He and his people were driven out—to stay out. Was violating the land of Canaan and terrorizing all its inhabitants the Jewish way of keeping the Ten Commandments? Where was Moses to see what they were doing—raping, murdering, and throwing people into the wilderness?

He must do something to expedite their return. Which course should he follow? Should he become a politician and lobby on behalf of his people around the capitals of the world? Perhaps he could carry the fight all the way to the United Nations. Did the outside world know what had happened to the Palestinians? Or should he become a writer, a filmmaker, a journalist and tell the world how they were uprooted and forced into the wilderness? For Yousif, the memory of that journey was indelible. The good people around the globe should know about it. They would sympathize, they would understand.

But to what end? Would they help him recover Ardallah? Would they send him home again? Not likely. What then must he do? It was a Herculean task that required the work of governments. Would people listen to him? Would his classmates go along with his plans? What plans? Where would the money come from?

Yousif tossed and turned in despair. The floor was hard under him. But his thoughts kept racing. Was Salwa agonizing as he was? He felt responsible for her and her mother and brothers, especially now that her father was dead. He must find her.

Yousif’s head buzzed with anguish. Maybe Salwa had stayed in Jericho, looking for him. My God! She didn’t have any money on her. What if she were separated from her family? What then? Some of the refugees who had not been able to find an apartment that afternoon had spoken of leaving for other cities, maybe even to Syria or Lebanon where the influx of refugees was perhaps less acute. The thought that Yousif might not find Salwa soon intensified his misery. His fingernails dug deep in his palm.

He thought of Basim and the men on the hilltops. Had they fallen victims? Had they paid for their birthright with their blood? When would he find out if they were dead? God, he hoped no ill had come to any of them—especially Basim. He was a leader one could trust. Yousif also hoped nothing bad had happened to ustaz Hakim. Or ustaz Saadeh. Or Izzat and Amin. How soon could they all organize—at least politically? What would their first order of business be? Surely to negotiate a return for all these masses before Israel had a chance to demolish their villages and obliterate any trace of their existence. But would the Arab regimes give a handful of zealous Palestinians a free hand? Not likely. Not soon anyway. Would Israel recognize such a group as a negotiating partner? Israel had not bled them only to resurrect them. It had meant for them to vanish. Even if lightning struck and Israel had a change of heart, what price would it exact?

Again Yousif heard his mother’s voice.

“How true Arabic proverbs are,” she reflected.

Yousif looked up. She was still sitting by the window, as though wary of closing her eyes.

“Which one do you have in mind?” he asked, his eyes drowsy.

“Niyyal illi binam bham ‘ateek.

Lucky is he who sleeps with an old worry. How very true! An old worry is over something that has already passed. A new worry is over something yet to come.”

Bitter years ahead, as implied in his mother’s words, did not frighten him. He lay on the floor, letting the phantoms of the future take shape in his mind. But when he heard her cry, an electric shock tore through him. He sprang to his feet and held her close to his body. Her sobbing was like distant rumbling before the apocalypse. He could feel her trembling, and his blood began to simmer.

He stared out the window. He could see the bare outlines of a few makeshift tents. The full moon hovered over them like a caretaker.

“Don’t cry, Mother,” Yousif said, massaging her shoulders. “I swear to you on my father’s grave, and on the graves of all the martyrs, that we will return.”

Yasmin tightened her grip around his waist and buried her head in his chest, sobbing.

“Don’t worry,” he said, his heart in his mouth. “It will all come to pass.”

Slowly, his mother withdrew from him. “He that believeth will make no haste,” she quoted, doom pouring out of her eyes. “Make no promises you cannot keep.”

“No, no,” he said, holding her hands, words gushing out of him like a spring fountain. The promise he had made to Salwa two nights earlier rang in his ears. “You must understand. The conscience of the world must be pricked, awakened. And we will do it. This is

not

an idle promise. And it’s

not

made in haste. We

shall

return. I promise you this on your honor and the honor of every mother weeping tonight. I promise you this for the sake of all of us who have been dispossessed—the families that have been denied their birthright and are now separated, the children who can’t sleep because they’re hungry, the babies who journeyed and died from thirst, the dead we left along the trail. Let this moon, which is staring at us like a grave one-eyed God, be my witness: we

shall

be delivered. We

shall

return.”

Ibrahim Fawal was born and raised in Ramallah, Palestine. He holds an M. A. in film from UCLA and a D.Phil from Oxford University. He worked with the renowned David Lean as the “Jordanian” First Assistant Director on

Lawrence of Arabia

. For twenty-five years, Fawal taught film and literature at Birmingham-Southern College and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. In 2001, the British Film Institute published Fawal’s book, Youssef Chahine, on the internationally-renowned film director who is known as the poet and thinker of Arab cinema.

Fawal’s novel

On the Hills of God

won the prestigious PEN-Oakland Award for Excellence in Literature and has been translated into Arabic and German. Critic Ishmael Reed calls it “a monumental book.”

Fawal currently resides in Birmingham, Alabama.

To learn more about Ibrahim Fawal and

On the Hills of God

, visit

www.newsouthbooks.com/onthehillsofgod

.