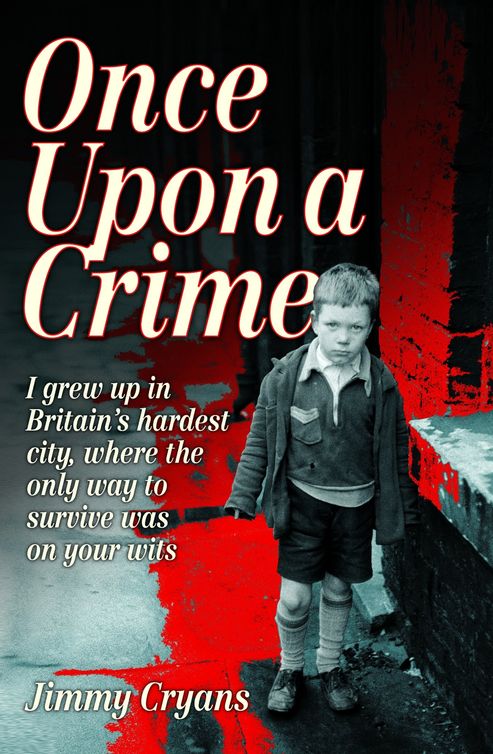

Once Upon a Crime

Authors: Jimmy Cryans

Dedicated to the memory of my ma, Sadie Cryans.

She was always there for me.

Title Page

Dedication

Preface

Foreword

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Epilogue

Plates

Copyright

T

hey say a leopard can never change its spots, but I do believe my own are starting to fade… at last!

Jimmy Cryans, February 2012

Glasgow High Court, Thursday 3 July 2008:

‘Stand up, Mr Cryans. You appear before this court today guilty of the premeditated and ruthless act of robbery and of using a prohibited weapon, namely a stun gun, which you did not hesitate to use against the manager of the premises who was rendered unconscious and was hospitalised. You carried a hand gun, wore a boiler suit and had your face covered with a balaclava, you escaped after emptying the safe of its contents which amounted to several thousands of pounds and none of which has been recovered. You are a dangerous and highly motivated criminal from whom the public needs to be protected. I take into account the mitigating factors put forward by counsel on your behalf and also your early plea of guilty, but a lengthy period of imprisonment is the only sentence this court will consider. You will therefore go to prison for an extended period of seven years. Take him down.’

I was a month shy of my 55th birthday.

G

rowing up in Glasgow in the 1950s and 1960s was an everyday adventure for me. There was always something happening and for the most part I had a happy childhood, even though right from as far back as I can remember I somehow felt different from all the other kids.

I was my mammie’s boy right from the off and it stayed that way until she died in October 2008. She was my best pal and all the good things about me I got from her. Of course this begs the question ‘Then where the fuck did all the bad things come from?’ All I can do is tell you my story how I remember it.

I was born in August 1953 at 1296 Duke Street in Parkhead in the east end. My ma had all six of her children delivered in her own bed in her own house. Ma didn’t like hospitals or doctors. When I made my entry I already had two big sisters, Sheena, the eldest and two years below her Olive, then aged eight. Ma’s name was Sarah but was known to everyone as Sadie. My da’s name was Hughie Cryans. The

Cryans were a well-known family, originally from the Calton but had lived in Parkhead for years. Ma’s family the Parks came from Bridgeton.

Ma and Hughie shared a bed recess in the front room/kitchen while I shared the big double bed in the back bedroom with my two older sisters. This was considered absolutely normal for the time and as I got older and went to visit pals I realised that we were considerably better off than most of them, but by any normal standards we were shit poor. The great thing about being a wean – a child – is that you just accept your lifestyle.

Even though I was struck down by polio at age two I have no bad memories. I was one of the lucky ones. Ma noticed very quickly that I was repeatedly falling over on my right side and rushed me to the doctor. Polio was confirmed and Ma’s early intervention saved me from a life in a wheelchair. Not for the last time was she to come to my rescue.

I recall my time at Quarrybray nursery school in Parkhead with fondness. I joined my first school at age five, again in Parkhead called Elba Lane Infants. From the start I loved school: it was new and exciting and I had lots of new pals. I can still reel off their names: Bobby McCallum, Jamie O’Donnell, Ian Cameron…

One day I arrived home from school bursting with excitement. ‘Ma, can I get a pair of those big boots like wee Fitzy’s got? Can I, Ma? Go on, please! They make loads of sparks when he slides alang the pavement.’

‘No, you’re not getting a pair of those parish boots, you’ll give us all a showing up,’ said Ma. Parish boots had metal soles that made big sparks and looked like boots I had seen soldiers wearing. Ma explained to me that they were part of a package of clothes given to the very poorest families and

arranged by the local parish church. I was bitterly disappointed and went to bed that night wishing that we were really, really poor – just like Fitzy’s family.

We lived at the top end of Duke Street and there were two main focus points for our entertainment. For me the most important was the Granada cinema where I got to know the big Hollywood stars. There were only two guys Glasgow men wanted to be: one was Jimmy Cagney and the other was Frank Sinatra and I think that tells you something about the psyche of the working-class Glasgow man.

The second centre of entertainment was the Palace Bar, which I was never allowed inside. Even Ma would not cross the threshold, but entertainment it certainly provided for me and the other dead-end kids, especially on Friday and Saturday nights. In those days pubs would call time at nine o’clock, by which time one of the local married women would have already entered the bar with sleeves rolled up. This would be swiftly followed by a screaming female voice that could have stripped paint at 20 yards. ‘Right, you fuckin’ useless wee shite – gies ma money and get yerself tae fuck!’

If we were really lucky the fight would spill out onto the pavement with the wife and her spouse trading punches. But the real highlight of the evening came for us at closing time. Sometimes trouble kicked off inside the bar and a group of men would spew out of the front doors. Best of all was when two men had decided to settle their differences in the

time-honoured

Glasgow fashion of a square-go: a jackets-off, face-to-face with no weapons involved and nobody else allowed to step in. Outside of these slim rules anything went: punching, kicking, gouging, head-butting (the famous Glasgow kiss) until one of the men would declare he had had enough or was beaten to an unconscious pulp. It may seem repulsive that

this savagery could be described as entertainment but for us kids it was just like watching a John Wayne movie at the Granada next door.

I was growing up in a violent culture but that’s the way life was and I never saw violence at home. I was loved by everyone and was a happy child. Though I always felt that there was something different, something missing, at this early time it wasn’t something that troubled me.

I

t was 2 December 1958. When I came through from the bedroom I could see my ma was still in bed, which was a first. My sisters Sheena and Olive and my da were all up and dressed and I could sense there was something different. ‘Do you want your breakfast?’ asked Olive.

‘Aye, I’ll have a roll and toasted cheese,’ I replied.

‘There’s nae cheese left,’ said Olive.

‘How no?’ I said.

‘’Cos the new baby has eaten it,’ came the reply.

I looked straight over at Ma still in bed, and for the first time noticed she had a small bundle cradled in the crook of her arm. ‘Come and say hello to your new wee brother. His name is Hughie.’

I was on the bed beside Ma in a flash and looked down into the face of my new brother. He looked just like one of the dolls I had seen some of the lassies playing with and I thought he was brilliant. There was a bond forged that day and it has lasted all our lives. We are totally different characters but just seem to fit each other perfectly.

In 1959 I was almost six years old and I loved going to school. My family didn’t have a television and our time was spent playing on the streets. I had discovered football and that I had a talent for it. We only lived about a five-minute walk from Celtic football club. I became a supporter not because they were my local team – this was Glasgow and the team you supported had nothing to do with locality but everything to do with what school or church you attended. There were lots of boys who lived in the same tenement as me who supported the city’s Protestant team, Rangers, whose ground was on the south side of the city.

My da was a tar man: he built new roads and worked all over the country and this would sometimes keep him away for weeks at a time. To this day if ever I smell new tarmac being laid I think of him. He was about 5ft 5in and built like a bull. He had enormous shoulders and forearms but was a very gentle man. He loved children of every description and I know for a fact that he loved my ma. The problem was that he would drink until he was literally legless. Ma didn’t take a drink except maybe one to toast the New Year and I never saw her even slightly merry because of alcohol. This led to friction and as the years passed by the arguments would become louder and more frequent. I never saw Hughie hit Ma but he would punch doors and walls, and I mean punch holes in them.

I once saw him fighting with two men one Friday night on the pavement outside the Straw House pub at Parkhead Cross and it is a sight I will never forget. What I did not know was that Hughie Cryans had a fearsome reputation throughout the east end as a fighting man and was not someone you crossed lightly. Three guys had entered the pub specifically to challenge Hughie, younger tough guys trying

to make a name by beating the main man. Well, by the time I came upon the scene on the pavement one of the three young guns was already unconscious inside the pub. Outside Hughie laid into the other two with a ferocity that took my breath away. This was a side to Da I had never seen before. There was quite a crowd gathered around but nobody said a word. When it was over Hughie calmly walked back into the pub to continue his evening’s drinking.

Many years later I asked him about that night and why he had given them such a severe beating. ‘Look, son,’ he said. ‘It was nae enough just to beat them, I had to make sure they wouldn’t come back. I had to kick the fight right out of them.’ Then he said a curious thing: ‘They were lucky.’ I asked him what he meant but all he said was, ‘Never mind.’

Ma was a seamstress and was a real wizard with a sewing machine. I was never without new, made-to-measure trousers, but she could also turn her hand to wedding dresses, jackets, skirts, blouses and curtains. Ma was a fine-looking woman, quite beautiful with raven-black hair and classic features. She was petite, about 5ft 2in and she had the heart of a lion. She would always make time for you no matter how busy she was. Right from the very beginning she was my soul-mate and not a day goes by when I do not think of her.

Sheena and Olive were always there for me too and I only have fond memories of us. Both of them attended the most prestigious Catholic school for girls in Glasgow, Charlotte Street, located in the east end. It was staffed by nuns and had a very strict regime but a high standard of education and was the stepping stone that led to university. Sheena was a bit of a scatterbrain, always laughing and doing daft things. Olive was much more practical and showed a serious side to the world to combat her natural shyness. I was never in any doubt about

how much the two of them loved me and there is also no doubt that I did at times take advantage of this, but they were wonderful sisters. We were a very close and loving family and that still remains the case.

I found school fairly easy and discovered early on that I had the ability to absorb and retain a lot of information. The down side to this was that I tended not to push myself as hard as I should have done. I was usually able to be in the top six with the minimum of effort and I look back on those years with regret.

At seven it was time for me to go to St Michael’s primary, located just across the road from me along near the end of Salamanca Street and adjoining St Michael’s Roman Catholic church. It was a really old school built in the middle of the 19th century but I was only to spend a few short months there before we all went to the brand new building. It was a strange experience to be surrounded by everything that shiny and new. The year was 1960 and Glasgow, just like every other major British city, was still trying to get back to some kind of normality after WWII.

Saturdays were always my favourite days. I would meet up with all my pals and we would make for the Granada picture house. There would sometimes be as many as a dozen of us and we would always try to commandeer the back row of the stalls. It was best when there was a big Hollywood blockbuster, during which we could act out the scenes along with the action on the big screen. Of course, this did not endear us to the other patrons and most especially to the usher. He was a real weasel of a guy who seemed to derive great satisfaction from what he seemed to believe was a position of authority. Whenever we were at our most boisterous he would stand at the end of our row of seats flashing his torch into our faces and shouting,

‘Right, ya wee rats – I know what yous are up tae and the lot of yous are for it.’

He would be answered by calls of, ‘Fuck off ya pervert! We’re going tae tell the manager you are trying to touch us up.’ This would send him almost completely over the edge and he would be jumping up and down and waving his arms about.

‘Ya fuckin’ bastards! I’ll kill the fucking lot of you. I’ll find out where you live and I’ll be round at yer doors!’

On some occasions the showing would descend into running battles in the aisles with groups of boys from other streets who were our rivals, which would result in a few bloody noses and the occasional black eye. I would always be right in the thick of it and discovered I had a talent for fighting even though I was easily the smallest of our group. I do not recall ever being frightened and was never intimidated by boys who were older or bigger than me. This led to me being the unofficial leader of our little group and I would be the one to come up with ideas about what our next adventure would be.