One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution (47 page)

Read One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution Online

Authors: Nancy Stout

The members of the new government went to New York City in April 1959. Fidel accepted an invitation to address the American Society of Newspaper Editors in Washington and a large delegation accompanied him to the United States. Here, Celia was photographed by Raúl Corrales as she made notes and took phone calls in a room in the New York Hilton on 54th Street and Sixth Avenue. (

Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos

)

About a month after this, writing from her new abode, she told Camilo Cienfuegos, “I am making an archive of the war with the original documents. Afterward, the archive will be filmed to be used and for our museum, it will be complete, from before Moncada. I also want to be sure that Fidel, all his speeches, all his writings, his letters, to the last paper [is included]. You could help me. Agreed? I’m interested in all your writings, your letters which are interesting because you write well and interestingly. A hug, Celia Sánchez M. [P.S.] Don’t put anything in order.”

She was finding a suitable role for herself and writing her own job description, as she began her new life as a member of the Revolutionary Government.

A COUPLE OF MONTHS LATER

, from April 15 through May 8, Celia was in the United States, a member of a large Cuban delegation. Fidel had accepted an invitation to address the American Society of Newspaper Editors, and traveled at the behest of the American media, not the U.S. government. Still, he wanted to shake hands with the president. Eisenhower did not meet with him, and left that up to his vice president, Richard Nixon. Castro’s biographers and historians have dreamed about what would have happened if the young warrior had met the old general. The new 26th of July government, a.k.a. the Revolution, was reaching out to the United States. Two months earlier, Camilo Cienfuegos and eight members of the new Cuban government had visited New York City on a goodwill tour scheduled to coincide with George Washington’s birthday. Camilo’s trip was unnoticed but important: it prepared the way for Fidel’s grand tour and sent a message to the United States that Cuba would like to be friends. In photographs, Camilo and his group look more like members of the Parks Department than representatives of a country; in contrast, Fidel and his entourage are somewhat stately.

They visited Mount Vernon, George Washington’s home, where Fidel talked to women volunteers and visiting schoolchildren, and they went to the Lincoln Memorial. Celia stood alone, contemplating Lincoln’s statue, and was photographed by Alberto Korda (although this photograph is rarely shown). They traveled to New York and were met at Penn Station by a crowd of 20,000 people, there to catch a glimpse of revolutionaries. They attended

an event in Central Park and Fidel received the ceremonial keys to the city; they went to City Hall, the United Nations, the Empire State Building, Columbia University, and the Bronx Zoo. They took a train to Princeton and Fidel spoke before a group of students. Celia was given a wrist corsage, which she wore on the upper sleeve of her uniform, converting it into a floral armband. They headed to Boston. In Bridgeport, New Haven, and Providence, Fidel got out of the train to shake hands. In Boston, he spoke before 8,700 students at Soldiers Field, while Celia went to see a Girona cousin who worked as a librarian at Harvard.

Celia was the caretaker of Fidel’s cigars, and had brought along a few extra boxes of Havanas. In Boston, they had enough to give a few to railroad porters and policemen as an expression of gratitude. These were not normal cigars. Fidel had found a shape he liked that was not too thick (that is, it wasn’t a fat businessman’s cigar, like the Churchill), long, and a bit like a knife and slender, a shape he called

lancero

. For security, it was rolled by one man. This cigar was made differently, too, rolled from a leaf that was blond as opposed to dark brown, and tasted smooth but was strong from extra fermentation. Fidel’s cigar had a new look: it was slim and new and powerful, like the Revolution. It was a young man’s cigar.

In one of these cities, Fidel met an Argentinean psychologist named Dr. Lidia Vexel-Robertson and started an affair with her of sufficient heat that, according to biographer Leycester Coltman, Dr. Vexel-Robertson made plans to move to Havana immediately.

31.

See the Revolution

WHEREVER THEY WENT

, Fidel urged his audience to visit Cuba and promised they’d find a low-cost, see-the-Revolution-at-firsthand vacation in the sun. If speaking to college students, he’d invite them to come to Havana on July 26th. Celia and he hatched this plan for a new kind of tourism, then went back to Havana and worked out the details. Here, for the first time after victory, she seems to have found a modus operandi. It became a pattern for how she worked with Fidel: he’d express an idea, and she’d put it into action. In the decades to come, she would play out the role of facilitator, the person he could count on to get his projects off the ground—and she threw some of her own into the mix.

“She was the engine,” Raúl Corrales, who worked many years for her, explained. On a practical level, this meant that Fidel would articulate a dream, a proposal, an idea, then he’d go on to the next meeting to address other issues, and Celia would pick up the phone. In this instance, directly following the trip, she started to work in INIT, the national tourist institute. There, she began spearheading their new kind of tourism for Cuba. (First, however, she and the rest of the delegation flew from Boston to Canada on a friendship tour, then on to Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and Trinidad and Tobago.)

The first tourist project under her authority was the installation of 8,000 lockers at Varadero Beach. It was a supremely practical and political gesture, and neither her idea nor Fidel’s, but one that had been proposed by the Orthodox Party leader, Eduardo Chibás, a decade earlier. The lockers were quickly installed and quite soon those fabulous beaches—with sand literally the color and consistency of refined sugar at the edge of miles of shallow, aqua-tinted water—were, for the first time ever, available to every Cuban. The beach front had previously been privately owned by U.S. or European citizens, and, as strange as it sounds, most Cubans had never seen it. Nor had the beaches been developed. Soon the new government decreed that workers had the right to have a vacation at the beach, and instituted buses that went there daily. “Elegant, affordable buses that served coffee and sandwiches on the trip,” my translator, Argelia Fernández, told me, with a tone of longing in her voice. Not long after installing the lockers, Celia had tree houses, or more precisely a series of sleeping platforms, built into some of the palm trees along the beach, so people had a place to sleep high above the sand. At the beginning of the Revolution people camped in tents on the beach for long periods, several weeks or a month, whatever vacation time was allowed them.

Celia promoted

Cubanismo

, pro-Cuban sentiment, emphasizing Fidel’s promise of a low-cost, see-the-Revolution type of vacation. At the same time she was pointing to a new kind of vacation, which wasn’t just for foreigners, since Cubans needed to get to know their country, too. Seeing Cuba became a goal that was promoted by her design teams, who quickly set about making other, previously off-limits venues available to the general population. “Celia worked in the INIT, the national tourist institute, while I was the accountant for that group,” Roberto Fernández explained. “She worked on a project called

La Vuelta a Cuba

, which translates best, although not literally, as Get to Know Cuba First, because people didn’t know the country. Many people had been to Paris, Miami, New York, but hadn’t traveled in Cuba.”

32.

The Urban

Comandancia

and the Zapata Swamp Resort

STEADILY, THROUGH THE EARLY MONTHS

following victory, Celia was building a home for herself and Fidel. By mid-1959, most of the other tenants in Celia’s apartment house had moved out as she took over the building. Her own apartment grew into an urban command post, with security guards stationed on the ground floor (and both ends of the street). Her first apartment, vacated by Silvia, was on the ground floor, but she soon got an apartment on the first (above ground) floor, and there installed a kitchen and a dining room with a big, easy-to-clean countertop, plus a few banquettes for seating, and filled planters with Sierra Maestra flora. Then she took the apartment across the hall—a two-bedroom apartment—for herself and furnished one of those rooms with a small library of books and a few pieces of her father’s furniture, his carved-walnut bed, and gave this room to Fidel. The turn-of-the-century carved furniture that her father had purchased in the early decades of the century was mostly too large for any of the rooms in this 1950s apartment building. Most of it was sent back to storage.

“When we were young, we spent our weekends at Once,” Flávia’s daughter, Alicia, told me. I was to hear this from several

of the nieces and nephews, from Chela’s son, Jorge, and Silvia’s sons, too. Everyone congregated in the kitchen and dining room apartment. “Fidel used to be more spontaneous. He would sleep in the next room, on my grandfather’s beautiful antique bed brought from Pilón. When he woke up, he’d go to the kitchen like any normal person, in his pajama pants. He’d get coffee. He was very natural. That life changed. It didn’t last long. He was still an idealist,” Alicia added.

The apartment building on Once was a far cry from the victors’ clubhouse of Celia’s imagination. At Once, she kept the lifestyle simple and didn’t bother to disguise the mundane architecture. “I went to her apartment weekly in the 1960s,” recalls her accountant, Roberto Fernández. “It was austere. Two chairs hung on the wall like in the country.” Time-saving efficiency became her new style.

Fidel was particularly interested in making public a legendary fish-and-game preserve in the Zapata Swamp (Ciénaga de Zapata), thought to have the best hunting and fishing in all of Cuba. Here again, Cubans had never actually experienced its bounty since this property had been privately owned since the sixteenth century by either Spaniards or North Americans. One of the first

La Vuelta a Cuba

projects became the Guama tourist center in the Zapata Swamp. Celia took over this project that Fidel initiated, which was meant to be a theme resort that resembled an Indian village. It can be seen in the opening scene of the film

I Am Cuba

, directed by Mikhail Kalatozov in 1964, a Soviet-Cuban production, as the camera zooms over thirty-eight palm-thatched cabins that stand on stilts above a lake, joined by a network of bridges.

Construction began in 1959; then everything came to a standstill when the project architect suddenly left the country. Since Guama was Fidel’s special project, Celia didn’t want a similar embarrassment to happen again. She needed an architect she could trust, and brought in Mario Girona—brother of Julio, Inez, Celia, and Isis—who was a society architect in Havana. Only a couple of years prior to this he’d designed the Hotel Capri for Meyer Lanksy. Girona explained his new role in the Revolution: “Professionally, as an architect, I worked with Celia, but first I want to make something clear: my grandfather and Celia’s father were cousins. Both were from Manzanillo. I am from Media Luna. My sister, Celia Girona, and Celia were children together in Media Luna.” The Girona and Sánchez parents and children had been the closest of friends, and Mario Girona was not going to leave Cuba.

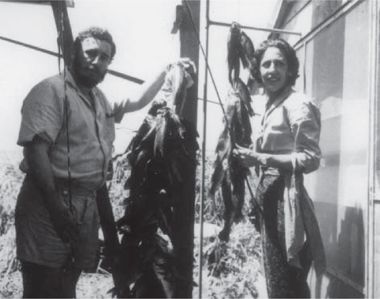

Fidel was particularly interested in making public a legendary fish-and-game preserve in the Zapata Swamp and began promoting this project almost immediately. Here, in a boat on Tesoro Lagoon, he and Celia display their day’s catch. (

Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos

)

Celia had telephoned Mario to ask if he would come to the Once apartment and told him they’d be meeting about a project. Both Fidel and Celia were there, and each explained the need to finish the Guama tourist center, which was far from finished. Girona said that “there was really nothing there. They had a house for the workers, the beginnings of a cafeteria. They had done some cabins. It was all being constructed in wood. I never worked with wood.” Fidel explained that the idea was that Guama would be constructed from wood, and that all the wood would come from the Sierra Maestra. Groups of trucks were hauling it in, and the wood for the foundations was so hard and dense it could withstand years in the water. Mario agreed, and before he left this meeting Celia gave him the project of installing lockers at Varadero (8,000 were still there in 2000). “People need to change their clothes,” she told him, but cautioned not to disturb “the beach flora.” Girona took care of this job immediately so he could get to Guama as soon as possible.