One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Air Power (24 page)

Read One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Air Power Online

Authors: Douglas V. Smith

Early 1932 saw one of the most dramatic events in the evolution of carrier aviation. For GJE No. 4, Blue (U.S.), with most of the Battle Force, including

Lexington

and

Saratoga

plus a constructive expeditionary force, had to recapture Hawaii from Black (Japan), which had taken it earlier.

32

Blue's Admiral Richard H. Leigh adopted a proposal by veteran airmen Rear Admiral Harry E. Yarnell and Captain John H. Towers for a surprise attack on Oahu by an “Advance Raiding Force” of the carriers and some escorts.

33

Departing the West Coast with the main body, on 5 February

the Advance Raiding Force separated from the fleet and proceeded to Hawaii independently. After a final twenty-five-knot run to about one hundred miles north of Oahu, the carriers began launching 150 aircraft in two waves before dawn on Sunday, 7 February. Achieving total surprise, the first wave hit Army air fields across Oahu and then went after the fleet and installations at Pearl Harbor. Army aircraft intervened, to little effect, and were themselves intercepted while returning to their bases by the Blue second wave, which inflicted heavy losses on the defenders.

Recovering their aircraft, the Blue carriers took evasive action, heading southwest of Oahu. At dawn on the 9th,

Saratoga

again raided Oahu while reconnoitering landing sites, once more with considerable success, though losing ten of the sixty-six aircraft engaged. Heading south, she linked up with

Lexington

overnight. By 11 February, Blue had effected landings on Oahu covered by aircraft from the carriers, though by then both were low on aircraft and

Lexington

was out of action due to enemy attack.

The critique of GJE No. 4 was acrimonious, as Army and Navy personnel disagreed on many issues. Nevertheless it was clear that the carrier raid on Oahu on Sunday morning, 7 Februaryâtermed by historian Thomas Fleming “a date that would live in amnesia”âhad thrown the defenders off balance, and they were never able to gain the initiative. Less than a decade later, the Japanese would open the Pacific War with precisely the same attack.

A month later FP XIII postulated that Blue (U.S.) was preparing a major offensive from Hawaii against the outer fringe of the Black (Japan) empire, a series of “atolls” at Puget Sound, San Francisco, San DiegoâSan Pedro, and Magdalena Bay, Mexico.

34

Blue's Admiral Leigh again had the bulk of the fleet, plus

Saratoga

(seventy-two aircraft), commanded by the aggressive Captain Frank R. McCrary, as well as thirty-six patrol planes and torpedo bombers based at Pearl Harbor and thirty-five battleship and cruiser floatplanes, plus a notional expeditionary force. Black's Vice Admiral Willard had

Langley

and Captain Ernest J. King's

Lexington

, with a total of ninety-eight aircraft, plus four aircraft tenders with thirty-six flying boats, and the airship

Los Angeles

, plus some surface forces.

Blue formed two principal task forces, a convoy and escort, and an offensive force composed of

Saratoga

, three battleships, and ten destroyers, to attack Puget Sound. Black, operating from the San PedroâSan Diego area, formed four task forces and a train. The “Striking Group,”

Lexington

with some cruisers and destroyers, was to intercept Blue at the earliest opportunity and inflict maximum damage to his forces, supported by submarine attacks to erode his strength in preparation for a surface action.

The maneuvers began on 10 March, with both fleets moving cautiously. Black submarines ascertained Blue's course, which suggested San Francisco was its objective. On the morning of the 13th, however, Blue altered course for Puget Sound while

the

Saratoga

Task Force remained on course for San Francisco, both as a deception and to provide cover for the rest of the main body. By morning on the 14th, the opposing carrier groups were hardly two hundred miles apart on a collision course, and scouts from

Saratoga

detected three Black cruisers. Alerted to each other's presence, the carriers launched air strikes against each other as the range closed early that afternoon.

Saratoga

aircraft inflicted 38 percent damage on Black's

Lexington

, but received 25 percent damage from enemy aircraft.

Captain King now convinced Willard to operate Black's

Lexington

independently against Blue's carrier, to reduce the enemy air threat. He moved

Lexington

out of range of

Saratoga

under cover of darkness, to gain sea room. During the 15th, clashes between surface forces began to develop as Black cruisers probed the outer perimeter of Blue's screen, though

Saratoga

aircraft sank two Black cruisers and heavily damaged a third. These strikes betrayed her position. Calculating that

Saratoga

would be recovering aircraft just before dusk, King moved

Lexington

in at high speed and launched a forty-nine-plane strike that hit

Saratoga

just as he had figured; the Blue carrier was ruled to have taken 49 percent damage, rendering her incapable of operating aircraft. The following day, Black destroyers “sank”

Saratoga

, rendering Blue bereft of carrier support. Although the maneuvers continued, the fleets lost contact on the 17th and the problem was ended.

The 1932 maneuvers reaffirmed the lesson that in carrier warfare, the first strike is the most important. Blue air commander Harry Yarnell concluded his critique by noting that

Lexington

and

Saratoga

were inadequate to the needs of a Pacific war, suggesting a minimum of six, if not eight, as a basic operational necessity, while Captain King argued that the Fleet Problem had demonstrated that carriers should be operated by divisions.

The Fleet Problem also added further evidence that the airship was of doubtful value as

Los Angles

had done nothing useful. Airship proponents brushed this aside, touting the merits of the new “flying aircraft carriers,”

Akron

(ZRS-4) and her sister

Macon

(ZRS-5), neither of which had taken part in the maneuvers. Nevertheless, in a prescient comment to CNO William V. Pratt, CinCUS Frank Schofield said “the need for aircraft is not more

Akron

s, but more carriers,” which seems to have summed up the fleet's opinion as well.

35

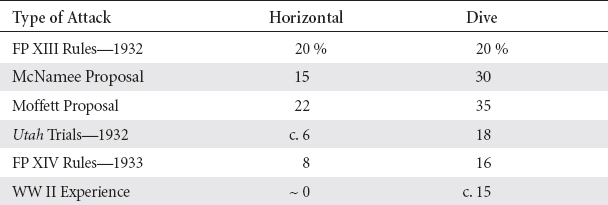

FP XIII brought to a head the contentious issue of the effectiveness of air attacks against ships. Neither World War I nor the events that followed provided any useful guidance, and an acrimonious debate had developed in the Serviceâand between the Navy and the Armyâover this question.

36

Rules for horizontal bombing and dive-bombing had been developed based on trials held during the late 1920s using dummy bombs against various targets. Following FP XIII, Commander, Battle Force (ComBatFor) Admiral Luke McNamee, considering the existing rules too optimistic,

proposed some revisions, while Rear Admiral William A. Moffett Jr., formidable Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, proposed even more generous guidelines.

About this time the target ship

Utah

(AG-16, ex-B-31) entered service. Trials with

Utah

produced figures even less optimistic than those proposed by McNamee, and new guidelines were issued for FP XIV (1933) over protests from aviation enthusiasts. In 1934 more optimistic rules were introduced, only to be rescinded in 1938. Wartime experience would prove that even the most pessimistic prewar guidelines were rather generous.

37

The Rules Debate: How Accurate in Terms of Bombs on Target Are Air Attacks against Maneuvering Capital Ships?

FP XIV was intended to test the fleet's ability to defend its bases from carrier raids and the effectiveness of carriers operating independently. Black (Japan) had to conduct a series of carrier raids against Blue (U.S.) bases on the West Coast in order to disrupt preparations for offensive operations. Black's Vice Admiral Frank H. Clark had

Saratoga

and

Lexington

and seven heavy cruisers, together the fastest ships in the fleet, plus some old destroyers and two oilers. Blue's Admiral Luke McNamee had virtually everything else in the fleet.

Since Black was to begin operations near Hawaii, the arrival of the carriers in the islands permitted a joint exercise with the Army's Hawaiian Department supported by local naval forces (27 Januaryâ1 February).

38

The defenders went on full alert on the 27th, when the carriers were still well to sea, as destroyers and some other vessels were dispatched to patrol northeastward of the islands. On the 29th the defenders initiated a twenty-four-hour air patrol out to 150 miles. Clark, not an aviator, adopted a plan devised by his airmen. Avoiding enemy air patrols, the carriers and some escorts arrived north of Molokai around midnight on 30â31 January, while a task group of heavy cruisers approached Oahu from the south. About two hours before dawn on the 31st the carriers put some ninety aircraft in the air, reserving

about forty for fleet defense. The strike force attained complete surprise, arriving over Pearl Harbor around dawn, and was ruled to have inflicted serious damage.

While the carriers proceeded to Hawaii and maneuvered with the Army, Blue prepared for the enemy raid.

39

Admiral McNamee concluded that Black was most likely to operate its carriers individually and conduct a series of simultaneous raids. Since the most critical Black targets were around San Francisco and San PedroâSan Diego, and knowing the range of the attacking aircraft, he formed two large task forces. The Northern Group's patrol area reached 100 miles from San Francisco, while the Southern Group reached 125 miles from San DiegoâSan Pedro. Each patrol area consisted of an outer perimeter of destroyers, submarines, and other vessels picketed more or less within sight of each other, supported by cruisers some miles to their rear, and battleships still further back, while flying boats patrolled beyond the outer edges.

As McNamee had calculated, Black's Clark decided to use his carriers individually to conduct two pairs of strikes on two successive days, hitting San Francisco twice and San Pedro and Puget Sound once each. Each carrier had three heavy cruisers as escorts, while his destroyers and oilers, unable to keep up with the carriers, formed a support group. The Carrier task forces began the problem roughly five hundred nautical miles south-southeast of Oahu on 10 February. The results were not impressive. Attempting to raid San Francisco on the morning of the 16th, the

Lexington

Task Force ran into fog, became lost, and was shortly intercepted by battleships and quickly dispatched.

Saratoga

had better luck, conducting extensive raids in the San Pedro area that morning, but she was also intercepted by enemy surface forces, barely escaping with some damage to her escortsâan experience repeated the following day when she undertook raids in the San Francisco area, once again barely escaping enemy battleships.

Critics of naval aviation argued that the outcome demonstrated the vulnerability of carriers operating independently, but carrier advocates rightly observed that the results were due to faulty planning and tactics, and to the limitations of training and equipment rather than to a flawed concept, noting that had the carriers operated together, they would have benefited from mutual support and the attacks could have been delivered with maximum possible force. Moreover, had the carriers and their personnel been equipped and trained for night operations, their effectiveness would have been greatly enhanced. Most importantly, however, they pointed to the need for longer-range aircraft, so that carriers could stand well away from their objectives; McNamee's 100â125-mile patrol areas around the critical ports had been dictated by the range of the existing carrier aircraft.

40

Vice Admiral Yarnell, commander of the

Saratoga

Task Force, observed that had the Black attack been made with six or eight carriers, it would likely have been devastating, and he called for more carriersâa goal already well in hand with USS

Ranger

(CV-4) about to be launched, USS

Yorktown

(CV-5) and USS

Enterprise

CV-6) about to be laid down, and USS

Wasp

(CV-7) soon to be ordered.

Some naval aviators believed that the outcome of the Fleet Problem had a major effect on command arrangements in the Navy. Apparently Vice Admiral Clark had been widely expected to be appointed Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet in 1934, but the post went to Joseph M. Reeves, the highest ranking aviator in the fleet. The aviators attributed this development to Clark's performance in the Fleet Problem.

41

The following year, FP XV (AprilâMay 1934) was a series of loosely connected tactical and operational exercises in the Pacific and the Caribbean, representing phases of a war with a European-Asian coalition.

42

The initial movement of the fleet to Central American waters was “harassed” by Brown (Japan) light forces, during which Blue's three carriers,

Lexington, Saratoga

, and

Langley

(a surrogate for

Ranger

), proved effective in providing anti-submarine protection to the fleet, while cruiser and battleship floatplanes proved useful for patrols and reconnaissance.