One minute to midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the brink of nuclear war (61 page)

Read One minute to midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the brink of nuclear war Online

Authors: Michael Dobbs

Photograph of the Banes SAM site, taken by the RF-101 pictured above on October 26.

[NARA]

Previously unpublished intelligence film of a U.S. Air Force RF-101 overflying the Soviet SAM site at Banes on October 26. The following day, October 27, a U.S. Air Force U-2 piloted by Major Rudolf Anderson was shot down by two missiles fired from this SAM site. Discovered by the author at the National Archives, the consecutive frames were cut and pieced together with Scotch tape by CIA analysts.

[NARA]

Flying right wing on Blue Moon Mission 2626, this U.S. Air Force RF-101, numbered 41511, took the photograph shown on front page from its left camera bay.

[NARA]

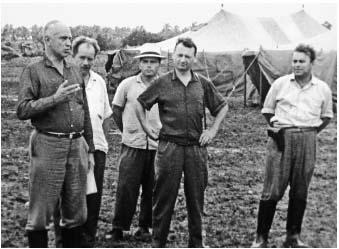

Colonel Georgi Voronkov (left), commander of the SAM regiment in eastern Cuba, congratulates officers responsible for shooting down Anderson's U-2. The officer on the right, with a pistol, is Major Ivan Gerchenov, commander of the Banes SAM site.

[MAVI]

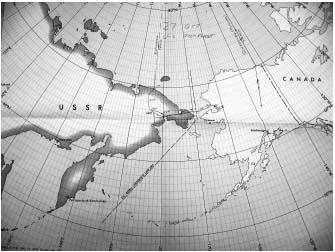

Previously unpublished map of U-2 pilot Captain Charles Maultsby's overflight of the Soviet Union, found by the author in State Department Archives.

[NARA]

Air Force photo of Captain Maultsby.

[Photo provided by Maultsby family]

Another U-2 pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson, was shot down over Cuba while Maultsby was in the air over the Soviet Union.

[Photo provided by Anderson family]

The mood was very different across the Potomac at the Pentagon, where the Joint Chiefs were busy refining their plans for a massive air strike against Cuba followed by an invasion. Curtis LeMay was already furious with Kennedy for postponing the planned attack until Tuesday. The Air Force chief wanted his fellow generals to go with him to the White House to demand an attack by Monday at the latest, before the missile sites became "fully operational."

Tickertape of the Radio Moscow broadcast was distributed around 9:30 a.m. on Sunday. The chiefs reacted with dismay. LeMay denounced Khrushchev's statement as "a charade," and a cover for keeping some weapons in Cuba. Admiral Anderson predicted that the no-invasion pledge being offered to Cuba by Kennedy would "leave Castro free to make trouble in Latin America." The generals were unimpressed by McNamara's argument that Khrushchev's concessions left the United States in "a much stronger position." They drafted an urgent message to the White House dismissing the Soviet move as "an insincere proposal to gain time" and warning that "there should be no relaxation of alert procedures."

"We have been had," Anderson told Kennedy when they finally got together.

"It's the greatest defeat in our history," insisted LeMay. "We should invade today."

Fidel Castro was at home in Vedado. He heard about the dismantling of the Soviet missile sites in a telephone call from the editor of

Revolucion,

Carlos Franqui. The Associated Press teletype was reporting the text of the letter from Khrushchev to Kennedy that had just been broadcast over Radio Moscow. The newspaper editor wanted to know "what should we do about this news?"

"What news?"

Franqui read the news bulletin over the phone and braced himself for an explosion.

"Son of a bitch! Bastard! Asshole!" Fidel went on in this vein for some time, "beating even his own record for curses." To vent his anger, he kicked a wall and smashed a mirror. The idea that the Russians had made a deal with the Americans "without even bothering to inform us" cut him to the core. He felt deeply "humiliated." He instructed President Dorticos to call the Soviet ambassador to find out what had happened.

Alekseev had been up late the night before. He was still in bed when the telephone rang.

"The radio says that the Soviet government has decided to withdraw the missiles."

The ambassador had no idea what Dorticos was talking about. There was obviously some mistake.

"You shouldn't believe American radio."

"It wasn't American radio. It was Radio Moscow."

11:10 A.M. SUNDAY, OCTOBER 28

The report reaching the North American Air Defense Command in Colorado Springs was startling. An air defense radar had picked up evidence of an unexplained missile launch from the Gulf of Mexico. The trajectory suggested that the target was somewhere in the Tampa Bay area of Florida.

By the time the duty officers at NORAD had figured out where the missile was headed, it was already too late to take any action. They received the first report of the incident at 11:08 a.m., six minutes after the missile was meant to land. A check with the Bomb Alarm System, a nationwide network of nuclear detonation devices placed on telephone polls in cities and military bases, revealed that Tampa was still intact. The Strategic Air Command knew nothing about the reported launch.

It took a few nerve-wracking minutes to establish what had really happened. The discovery of Soviet missiles on Cuba had resulted in a crash program to reorient the American air defense system from north to south. A radar station at Moorestown just off the New Jersey Turnpike had been reconfigured to pick up missile launches from Cuba. But the giant golfballlike installation was still experiencing teething problems. Technicians had fed a test tape into the system at the very moment that an artificial satellite appeared on the horizon, causing radar operators to confuse the satellite with an incoming missile.

A false alarm.

The ExComm began meeting at 11:10 a.m., after JFK returned from church, just as NORAD was clearing up the confusion about the phantom missile attack on Tampa. Aides who had expressed doubts about Kennedy's handling of the crisis a few hours earlier now vied with each other to praise him. Bundy coined a new expression to describe the divisions among the president's advisers that had erupted in dramatic fashion on Saturday afternoon.

"Everyone knows who were the hawks and who were the doves," said the self-appointed spokesman for the hawks. "Today was the day of the doves."

To many of the men who had spent the last thirteen days in the Cabinet Room, agonizing over the threat posed by Soviet missiles, it suddenly seemed as if the president was a miracleworker. One aide suggested he intervene in a border war between China and India that had been overshadowed by the superpower confrontation. Kennedy brushed the suggestion aside.

"I don't think either of them, or anybody else, wants me to solve that crisis."

"But, Mr. President, today you're ten feet tall."

JFK laughed. "That will last about a week."

Kennedy drafted a letter to Khrushchev welcoming his "statesmanlike decision" to withdraw the missiles. He instructed Pierre Salinger to tell the television networks not to play the story up as "a victory for us." He was worried that the mercurial Soviet leader "will be so humiliated and angered that he will change his mind."

Exercising restraint proved difficult for the networks. That evening, CBS News broadcast a special report on the crisis "brought to you by the makers of Geritol, a high potency vitamin, iron-rich tonic that makes you feel stronger." Seated in front of a map of Cuba, correspondent Charles Collingwood tried to put the latest developments in perspective. "This is the day we have every reason to believe the world came out from under the most terrible threat of nuclear holocaust since World War II," he told viewers. He described Khrushchev's letter to Kennedy as a "humiliating defeat for Soviet policy."

Bobby Kennedy had missed the early part of the ExComm meeting because of a hastily arranged meeting with the Soviet ambassador. Dobrynin officially conveyed Khrushchev's decision to withdraw the missiles from Cuba and passed on his "best wishes" to the president. The president's brother made no attempt to conceal his relief. "At last, I am going to see the kids," he told the ambassador. "Why, I've almost forgotten my way home." It was the first time in many days that Dobrynin had seen RFK smile.

On instructions from Moscow, Dobrynin later attempted to formalize the understanding on removing the American missile bases in Turkey with an exchange of letters between Khrushchev and Kennedy. But Bobby refused to accept the Soviet letter, telling Dobrynin that the president would keep his word but would not engage in correspondence on the subject. He confided that he himself might run for president one day--and his chances could be damaged if word leaked out about a secret deal with Moscow. Despite the determination of the Kennedy brothers to avoid creating a paper trail, dismantling of the Jupiters would begin as promised, five months later, on April 1, 1963.