Oogy The Dog Only a Family Could Love (3 page)

Read Oogy The Dog Only a Family Could Love Online

Authors: Larry Levin

This is Oogy’s story. It is, in the truest sense, a one-in-a-million tale. To tell it accurately necessarily intertwines other stories, those of the people who saved Oogy and all the people who love him, including my family. Part of the wonder has been how, over time, all who have come in contact with Oogy, learned his story, and experienced his genuinely gentle nature and noble bearing have been touched. And because I talk to people every day who have rescued many, many pets of their own, this is a testament to their collective efforts as well.

“You’re here now,” I tell him. “It’s okay.”

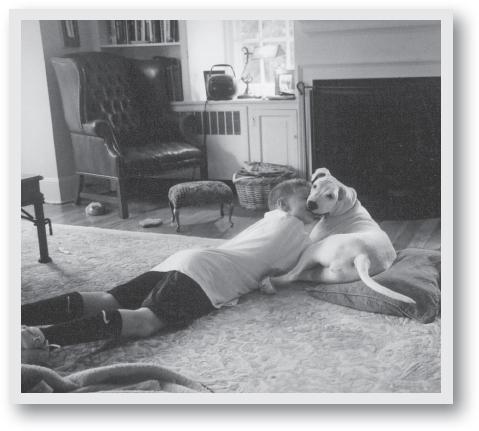

In his sleep, Oogy’s legs begin to twitch; he must be dreaming that he is running. I imagine the scene, because it is so common: It is sunny and late in the day at the dog park; the heat-dried grass scents the wind. Oogy trots across the plateau to where I sit at a picnic table, past a dozen other frolicking dogs, just so that I can touch his head. His distorted face seems to be smiling. Or maybe he really is. I touch my fingers to both sides of his head and kiss him on the nose.

“Go on, you big galoot,” I tell him.

Oogy turns to find another dog to play with a while longer.

The Patron Saint of Hopeless Causes

t

he first time I met Oogy, a veterinarian told me that police had found him in a raid and were directed to take him to Ardmore Animal Hospital (AAH) in Montgomery County, PA, by the local Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA). Dr. James Bianco, the surgeon who saved Oogy, told me that he recalled the raid had been on a home because of suspected drug activity. For years, I took the story of Oogy’s arrival at Ardmore at face value. It didn’t matter to me how Oogy had gotten to the hospital that saved him; it was enough for me that he had been saved. I had no reason to question the explanation with which I had been provided. But eventually, prompted by the curiosity of a reporter friend, I started asking questions to see what I could find out about the chain of events that had culminated in Oogy coming to live with us. I found myself driven to see what I could discover about the actual events themselves. I had to know as much about the truth as I could find out. And even though I learned that it was unlikely the story I’d been told was what had actually happened, I also learned that discovering the actual events surrounding Oogy’s arrival might well prove to be impossible.

It would not have been unusual for the police and the SPCA to work in concert during the raid in which Oogy was discovered. Experience had taught the police and the SPCA that wherever dogfighting occurs, there is a substantial chance that other illegal activities are going on, often involving drugs, weapons, and undeclared cash. As a result, the police routinely accompany the SPCA on dogfighting interventions, and the SPCA routinely joins police in, or is available for, drug raids.

Drug dealers fight dogs for money and sometimes simply for bragging rights. They also keep fighting dogs around to protect the drugs and, on occasion, to scare away the competition. This type of operation represents the lowest level of what is now an industry generating over five hundred million dollars a year, commonly referred to as the “street-fighting” aspect of the business. The dogs involved in this lead the most horrific lives imaginable: They are brutalized to toughen them and to make them angry; their injuries are often either not treated or are treated in a rudimentary way (street-fighting dogs have been found with gashes, tears, and cuts stapled together); and they are bred, housed, and trained under the most barbaric conditions. There are also amateur and professional levels of dogfighting, in which an increasing amount of time and money is spent to breed and train the dogs and even to provide some basic medical care for them. Recently, a fourth level of dogfighting has emerged, combining significant financial resources with street-fighting sensibilities.

Fighting dogs who will not fight or who lose fights are occasionally released, but more often than not, they are destroyed in a variety of inhumane ways: They are shot, drowned, bludgeoned, electrocuted, garroted, hung, stabbed, or, as probably happened to Oogy, given to other dogs to be torn apart. The fact that when we first met Oogy we were told that he was a pit bull suggests to me that the dealer who most likely used him for bait thought that he was a fighting dog who would not fight.

When police find fighting dogs in a raid in which they are not accompanied by the SPCA, standard procedure requires them to have the dogs transported there. The SPCA in Philadelphia told me that the Philadelphia police would not have been in Montgomery County, nor would they have taken an animal seized in a raid in Philadelphia to a shelter in Ardmore. According to the director of operations for the Montgomery County SPCA, when police find an injured animal and call while the facility’s operations are open, the animal will be brought there, where two surgeons are on call to provide emergency treatment. Given the extent of Oogy’s injuries, had he been taken to that facility following the raid in which he was found, it is a virtual certainty that he would have been destroyed. The surgeons would have been faced with hours of costly procedures that, given the severity of the wounds and the myriad other medical problems they would have had to deal with, might well have proved futile. On top of that, the SPCA did not have unlimited resources to rehabilitate fighting dogs, particularly at the expense of the other animals in its care. There was no way of determining in advance whether rehabilitation efforts would be successful; after these efforts had been made, a fighting dog might still pose a threat to other animals, or even humans, in which case it could never be made available for adoption. Since time, effort, and money spent on rehabilitation attempts meant that resources would be denied to other dogs with a real likelihood of being adopted, fighting dogs almost invariably would be destroyed. The chances of a mutilated fighting dog being rehabilitated, even if it could have been saved through hours of surgery and postsurgical treatment, and then adopted were beyond remote.

At the time of Oogy’s rescue, Ardmore was the only animal hospital in the immediate area to offer after-hours emergency room treatment. Had the police called the Montgomery County SPCA after hours, when the facility’s operations were closed, a dispatcher would have had the authority to direct the police to take a wounded dog to Ardmore’s ER. The Montgomery County SPCA has no record of that happening, and no follow-up report, which would have been generated had they directed the police there. In fact, the SPCA did not pick up or receive any fighting dogs at all on the weekend that Oogy was found. When I asked the SPCA’s director of operations whether the presence of a bait dog would have necessarily meant that there had to have been fighting dogs at the site, and wondered why none had been taken to the SPCA as a result of the raid in which Oogy was found, the director told me that very often the owners “drop the dogs” — let them loose so that they will not be charged with animal cruelty. “The dogs usually turn up in a couple of days,” he told me, “either as strays or when they corner somebody on the roof of their car.”

I later learned that another possible reason no other fighting dogs were found in the raid is that dogs being used for street fighting are often kept at a different location from where they are fought. Since those who fight dogs are usually not concerned with providing proper care for them, the dogs are often stashed in abandoned properties so that if they are discovered, there will be no way to find the owners. And to make detection more difficult, dogfighters also regularly change the locations where they train the dogs and hold the fights.

The fact that no other dogs were found in the raid in which Oogy was discovered also suggests that Oogy may have been abandoned after he was attacked. Since there were no other animals in the house, there would have been no reason for anyone to stay there with a dying dog, especially a dog that had been abused when it was alive.

In the absence of any evidence that the Montgomery County SPCA directed that Oogy be taken to the Ardmore ER, I’m left with only one explanation as to how Oogy got to the hospital — and although it is speculative, it makes the most sense to me. I believe that Oogy was found in a local police operation, which is consistent with Dr. Bianco’s recollection, and because the raid was local, the police knew about the emergency services that were available after hours through Ardmore. My best guess is that some animal-loving cop found a mutilated, dying puppy and, on his or her own initiative, brought the dog to the emergency services at Ardmore to try to save its life.

In the end, the only important thing is the fact that Oogy was discovered and brought in for treatment. I can never know why the fighting dog that attacked Oogy, and that would have been or was being trained to kill, did not in fact kill him. The emergency room services were eliminated several years after Oogy was found, and all of the ER records are gone, so I have no way of knowing if its staff ever wrote down which police department brought him in. I was told that the ER staff would probably not have bothered to note the department because it wouldn’t have been relevant to treatment. I tried to locate the two doctors who had operated the ER to see what, if anything, they remembered, but I couldn’t track them down. As a result, I cannot determine how the police came to learn about and raid the drug-dealing operation, or where exactly the raid occurred, or what actually happened during the raid and what was found. I can’t learn the fate of any people who may have been there when the police burst in. I can never know how long Oogy lay in his cage and suffered or what that suffering consisted of. I will never know why his keepers did not kill him and put him out of his misery when they saw that the dog being trained to kill had not finished the job.

My investigation into the events that culminated in Oogy coming to live with us also revealed that after the police rescued him, Oogy survived largely because of one woman’s refusal to let him die and the efforts of a surgeon and veterinary staff who operated out of the purest of motives: to save the life of a helpless creature before them.

Diane Klein, the hospital administrator of AAH, began working with Dr. Bianco when she was just out of college, a year before he acquired the facility in 1989. The first year that the hospital was open for business, Dr. Bianco and Diane each worked one-hundred-hour weeks, yet Dr. Bianco did not generate enough income to feed his family by himself. Luckily, his wife was working at the time. For the first two years the hospital was open, Diane slept in a room on the second floor and constituted the entire staff. She worked as Dr. Bianco’s assistant, managed the schedule, paid the bills, ordered supplies, kept inventory, and clipped toenails. Diane had graduated from college with a degree in biology and aspired to become a veterinarian herself. When she started with Dr. Bianco, she was taking night courses with that goal in mind. As the volume of business increased and the staff grew, in appreciation of her dedication and skills, Dr. Bianco offered to pay for Diane to get a degree in veterinary medicine. By that time, though, Diane had married and had her first child, and she felt her time and energy were better spent focused on her family. Dr. Bianco then asked Diane to manage the office. Along the way, he also made her a partner in the business.

Both Dr. Bianco and Diane are completely committed to helping animals and will do whatever is required to achieve that end. They enjoy a professional relationship that is based on an implicit trust in each other’s judgment. Ardmore Animal Hospital’s national recognition reflects the professionalism and compassion that starts at the top.

“Diane loves gladiator dogs,” Dr. Bianco explained to me. “But, ultimately, her generosity goes beyond this. There is no purer animal lover. She has a special affinity for dogs not given a fair shake.” He paused, thought a moment, and then continued, “This business attracts a lot of people who relate better to animals than they do to humans. I’ve had more than one technician who rode with outlaw motorcycle gangs. I’ve had technicians who were literally incapable of speaking to my clients. Diane is a special blend of animal lover and people person. She is so dedicated to helping animals that she is very demanding of the staff.” He smiled. “I wouldn’t say the staff is afraid of her, but they certainly have a very healthy respect for her. The thing is, she is no more demanding of the staff than she is of herself.”

By her own admission, Diane would make a lousy animal rights advocate. “It must be the Italian in me. I have no tolerance for people who abuse animals. I’m not capable of reasoning with them. I couldn’t deal with these people rationally. But then, there’s nothing rational about them.” She laughed. “I’d go after them with a hammer.”

Monday, December 16, 2002, was the second anniversary of the death of Diane’s all-time favorite dog, Maddie, a Staffordshire terrier–bulldog mix that had been with Diane for thirteen years, ultimately succumbing to cancer. The night before, she and her husband had looked at some videos of the dog. At first, they had laughed at Maddie’s antics, but eventually their sense of loss overcame them, and they had cried and comforted each other. On the drive to work that Monday morning, Diane was unable to stop thinking of Maddie, remembering favorite moments. She felt down, a bit distracted.