Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory (55 page)

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Europe, #History, #Great Britain, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #Intelligence, #Political Freedom & Security - Intelligence, #Political Science, #Espionage, #Modern, #World War, #1939-1945, #Military, #Italy, #Naval, #World War II, #Secret service, #Sicily (Italy), #Deception, #Military - World War II, #War, #History - Military, #Military - Naval, #Military - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #Deception - Spain - Atlantic Coast - History - 20th century, #Naval History - World War II, #Ewen, #Military - Intelligence, #World War; 1939-1945 - Secret service - Great Britain, #Sicily (Italy) - History; Military - 20th century, #1939-1945 - Secret service - Great Britain, #Atlantic Coast (Spain), #1939-1945 - Spain - Atlantic Coast, #1939-1945 - Campaigns - Italy - Sicily, #Intelligence Operations, #Deception - Great Britain - History - 20th century, #Atlantic Coast (Spain) - History, #Montagu, #Atlantic Coast (Spain) - History; Military - 20th century, #Sicily (Italy) - History, #World War; 1939-1945 - Campaigns - Italy - Sicily, #Operation Mincemeat, #Montagu; Ewen, #World War; 1939-1945 - Spain - Atlantic Coast

Ewen Montagu was appointed OBE for his part in Operation Mincemeat. He returned to the law, as he had always intended, and in 1945 he was appointed judge advocate of the fleet, responsible for administering the court-martial system in the Royal Navy. He would hold that post for the next eighteen years, while also serving as a judge in Hampshire and Middlesex, and recorder, successively, of Devizes and Southampton. Montagu lived a double life; alongside the feared judge and pillar of Anglo-Jewish society was another Ewen Montagu: the dashing wartime intelligence officer with an extraordinary story to tell.

As a judge, Montagu proved scrupulously fair, wonderfully rude, and almost always embroiled in one controversy or another. The press nicknamed him “the Turbulent Judge.”

49

In 1957, he remarked in court, while trying a merchant seaman: “Half the scum of England

50

are going into the Merchant Navy to escape military service.” He apologized. Four years later, he told an audience of Rotarians: “A boy crook should have

51

his trousers taken down and should be spanked by a policewoman with a hairbrush.” He apologized again. When deliberations in court displeased or bored him, he would groan, sigh, roll his eyes, and crack inappropriate jokes. Barristers complained often about his offensive behavior. He apologized and carried on. His corrosive humor was usually misunderstood; his wit was so sharp and sarcastic it could humble the most arrogant barrister, and did so, frequently. In 1967, a pimp appealed his conviction, arguing that Montagu had been so rude to his lawyer that he deserved a retrial. The appeal was rejected on the grounds that “discourtesy, even gross discourtesy

52

to counsel, however regrettable, could not be a ground for quashing a conviction.”

Often he would impose a lenient sentence on an offender, acting on a hunch that the man or woman genuinely planned to go straight. His hunches were seldom wrong. “If a man can’t have a stroke of luck

53

once in his life, it’s not much of a life.” But to those who should know better, or seemed incorrigible, he was merciless. Sentencing the actor Trevor Howard for drinking at least eight double whiskeys and then driving into a lamppost, he said: “The public needs protecting

54

from you, you are a man who drinks vast quantities, every night, yet you have so little care for your fellow citizens that you are willing to drive.” Summing up his career, one contemporary wrote: “Few judges have trodden

55

so hard on the corns of so many people’s dignity as this tall, witty, testy, wartime naval commander with the sensitive face and the turbulent tongue. But few judges have been so quick to apologise with the air of a boxer shaking hands after a fight.” Montagu was aware of his own shortcomings. “Perhaps I should have been more

56

patient,” he once said. “It is fair, I think, to say that I don’t suffer fools gladly.” In truth, he did become more patient and tolerant with age. He also became more devout, plunged into numerous charitable works, and became president of the United Synagogue.

Montagu had lived an extraordinary life, as a lawyer, intelligence officer, and writer: a judge of deep seriousness, he had also retained a boyish side and a talent for self-mockery. Without his combination of “extreme caution and extreme daring,”

57

Operation Mincemeat could never have happened. The entire plan was, in a way, a reflection of his sense of the ridiculous and his love of the macabre, of playing a part. In 1980, a photograph of Jean Gerard Leigh appeared in the

Times

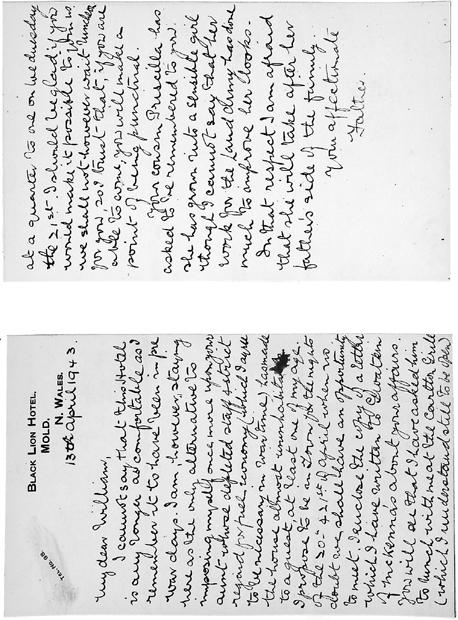

after her husband was made CBE. “Dear

58

‘Pam,’” wrote Montagu, now seventy-nine years old. “It was a voice from the past to see you in today’s papers and I can’t resist being another such voice and sending you congratulations. Ever yours, Ewen (alias Major William Martin).”

Shortly before his death, Montagu received a letter from the father of two young Canadian girls, who had read of his wartime exploits, requesting a memento. He immediately replied, enclosing “one of the buttons I wore

59

when carrying out Operation Mincemeat,” along with some advice: “Keep a real sense of humour.

60

By real I don’t mean just to be able to see a joke, but to be able to really and truly laugh at oneself.”

Ewen Montagu died in 1985, at the age of eighty-four, believing he had successfully hidden, for all time, the identity of the body used in Operation Mincemeat.

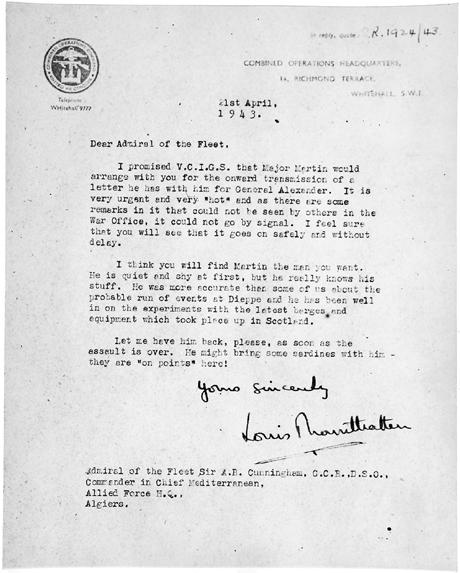

Roger Morgan, a council planning officer and an indefatigable amateur historian, began researching the story of Operation Mincemeat in 1980. He wrote to Montagu and later met him and, like every other would-be sleuth, received a response that was as courteous as it was unhelpful. Like most others, Morgan concluded that the secret of Major Martin’s identity had died with Montagu: the man who never was would never be. But then, in 1996, Morgan was leafing through a newly declassified batch of government files when he came across a three-volume report on Ewen Montagu’s wartime activities, including a copy of the official account of Operation Mincemeat, written just before the end of the war. “There, at the end

61

of the last volume, staring out at him was the answer to many sleepless nights.” The official censor, perhaps unaware of the extraordinary efforts of concealment made over the preceding half century, had failed to redact a name. “On 28th January there had died

62

a labourer of no fixed abode. His name was Glyndwr Michael and he was 34 years old.”

N

UESTRA

S

EÑORA DE LA

S

OLEDAD

cemetery is a ghostly but tranquil place at dusk. Swallows swoop over the cobbled paths, and the cypresses stand sentry. Far out in the bay, you can see the fishing boats bringing in the sardines. As the sun sinks and dusk settles, the graves seem to merge into one long field of engraved marble, stories of lives long and short, full and empty. One of the gravestones is different. It tells of a double life, one brief, sad, and real, the other a little longer, entirely invented, and oddly heroic. The body in this grave washed ashore wearing a fake uniform and the underwear of a dead Oxford don, with a love letter from a girl he had never known pressed to his long-dead heart. But he was not alone in fitting more than one personality into a single life. No one in this story was quite who they seemed to be. The Montagu brothers, Charles Cholmondeley, Jean Leslie, Alan Hillgarth, Karl-Erich Kühlenthal, and Juan Pujol—each was born into one existence and imagined himself into a life quite different.

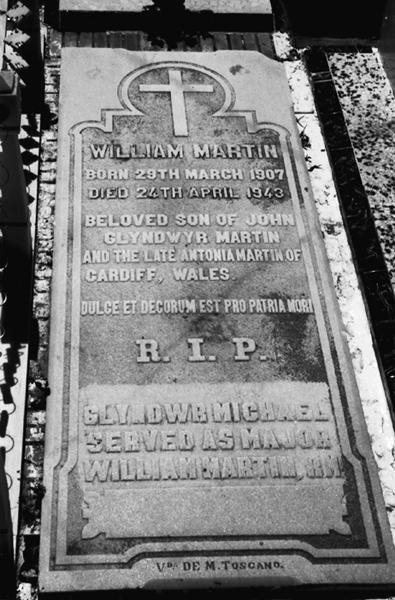

Grave number 1886 in Huelva cemetery was taken over by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in 1977. In a small local armistice, it is now maintained, on behalf of Britain, by the German consulate in Huelva. Every year, in April, an Englishwoman from the town lays flowers on the gravestone.

In 1997, half a century after Operation Mincemeat, the British government added a carved postscript to the marble slab:

Glyndwr Michael

63

served as

Major William Martin, RM

Appendix