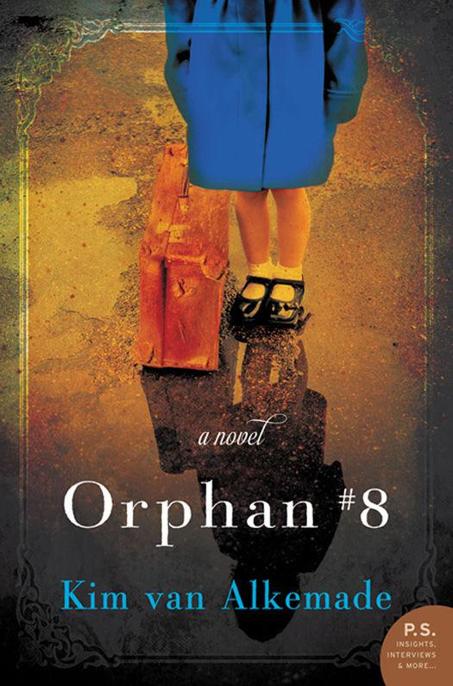

Orphan #8

Authors: Kim van Alkemade

To the memory of my grandfather Victor Berger,

“the ever-efficient boy of the Home”

Contents

- Dedication

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

- Chapter Seventeen

- Chapter Eighteen

- Chapter Nineteen

- Chapter Twenty

- Chapter Twenty-one

- Chapter Twenty-two

- Acknowledgments

- References

- P.S. Insights, Interviews & More . . . *

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

F

ROM HER BED OF BUNDLED NEWSPAPERS UNDER THE

kitchen table, Rachel Rabinowitz watched her mother’s bare feet shuffle to the sink. She heard water filling the kettle, then saw her mother’s heels lift as she stretched up to drop a nickel in the gas meter. There was the sizzle of a struck match, the hiss of the burner, the whoosh of catching flame. As her mother passed the table Rachel reached out to catch the hem of her nightdress.

“Awake already, little monkey?” Visha peered down, her dark hair hanging in loose curls. Rachel nodded, open eyes eager. “You’ll stay put until the boarders leave for work, yes? You know it makes me nervous when there’s too many people crowding in the kitchen.”

Rachel stuck out her bottom lip. Visha tensed, still afraid of sparking one of her daughter’s tantrums, even though months had gone by since the last one. Then Rachel smiled. “Yes, Mama, I will.”

Visha let out her breath. “That’s a good girl.” She stood and knocked on the front room door, two sharp raps. After hearing the boarders’ muffled voices assure her they were awake, she crossed the kitchen and let herself out of the apartment. Going down the

tenement’s hallway to use the toilet, she allowed herself to think their trouble with Rachel was really over.

It had started with the colic, but she couldn’t blame the baby for that, though Harry seemed to. For months, it wailed at all hours of the night. Only if she held it in her arms and paced the kitchen did the cries settle into sobs that at least the neighbors could sleep through. They hadn’t been able to keep boarders then—who would pay to sleep next to that racket?—and Harry started working late to make up the income. To avoid the baby, he took to spending more nights at his Society meetings. Sundays, too, he’d managed to escape, taking Sam up to the Central Park or down to the piers to watch the ships. Visha might have gone crazy, boxed up in those three rooms with an infant who seemed to hate her. It was only Mrs. Giovanni coming by every day, for a visit so Visha could talk like a person, or to take the baby for an hour so she could rest, that got her through those long months.

Back in the kitchen, Visha poured boiling water into the teapot and also into a basin in the bottom of the sink before filling the kettle again and setting it back on the flame. She tempered the water in the basin with a splash of cold and set out a hard square of soap and a threadbare towel. She put the teapot, two cups, a jar of jelly, a spoon, and the slices of yesterday’s bread on the table. In the front room, furniture scraped across the floor, then the door opened, and the boarders, Joe and Abe, emerged. The young men were bare chested, suspenders drooping from the waists of rumpled trousers, their untied laces slithering as they walked. Visha settled two damp shirts on the backs of the kitchen chairs. She’d washed them out late the night before, and at least they were clean if anyone complained. Abe went down the hall while Joe leaned

over the sink to wash up. Visha edged past him into her bedroom and shut the door.

She lifted off her nightdress and hung it from a nail in the wall, then buttoned up a white shirtwaist over her shift and stepped into a long skirt. Her husband yawned when Visha sat on the bed to pull up her stockings. Harry’s arm still stretched across her pillow from last night, when he’d stroked her shoulder and whispered in her ear: “Soon, my Visha, soon, when I’m a contractor with my own business, we’ll move out of this tenement and up to Harlem, maybe even the Bronx. The children will have their own bedroom, we won’t have to take in boarders, and you can sit all afternoon with your feet up like a queen, my queen.” As he spoke, Visha pictured herself in the quiet bedroom of a new apartment building, windows open to the cool outside air. She imagined filling a tub in a tiled bathroom with hot water just waiting for her to turn the tap.

Visha had turned to Harry then, inviting. He moved over her quietly, the way she liked, not like Mr. Giovanni next door, whose grunts echoed in the stinking airshaft. She kept him inside her to the end, her heels pressed into the backs of his knees, the prospect of his success stirring her desire for another baby. Rachel was four years old already, the sleepless nights a long-ago memory, the tantrums apparently over. After Harry rolled off of her, Visha dreamed of the feathery weight of a newborn in her arms.

Rachel was getting restless as the boarders sat in the kitchen, stirring jelly into their tea and soaking their bread to soften it. From under the table, she reached out and tangled Joe’s shoelaces.

“What is this now happening? Is there rats chewing on my boot strings?”

Rachel laughed. She nudged her brother beside her to wake up. “Tie them in knots, Sam, so he falls down,” she whispered. “I can’t tie knots yet.”

Joe heard her. “What for you want me to fall over, to break my neck maybe? Be careful I don’t pull you from under there and make trouble with your mother.”

Sam wrapped his arms around his sister. “Don’t start now, Rachel. Be good and quiet and I’ll teach you what number comes after one hundred.”

Rachel let go of the laces. “There’s more numbers

after

one hundred?”

“Do you promise to be still until Mama says we can come out?”

Rachel nodded vigorously. Sam whispered in her ear.

“Say it again.” He did. Rachel laughed like when she tasted something sweet.

“One hundred

and

one hundred

and

one hundred.” Sam put his head down on the newspapers and listened, satisfied, to his sister’s chanting.

Back in September when he started first grade, Rachel had gotten it into her head that she would be going to school with Sam. When he walked out the door without her, she had thrown a fit that was still going on when he came home for lunch. Rachel’s screaming had driven even Mrs. Giovanni away and Visha was beside herself. “See what you can do with her!” she said to Sam, then shut herself up in the bedroom.

Sam had managed to calm his sister by teaching her the first five letters of the alphabet. Before he went back to school for the afternoon, his stomach rolling with hunger, he’d struck their bargain. For quiet and goodness, Sam paid Rachel with letters and

numbers. It was April now, and already she knew as much as he’d been taught. That first day, Visha made up for his missed lunch by preparing for Sam his favorite dinner, pasta with tomato gravy just like Mrs. Giovanni’s. “You saved my life today,” she’d told her son, kissing the top of his head.

Visha, dressed, came in from the bedroom to make the boarders their lunches, wrapping cold baked potatoes and fat pickles in newspaper. Chair legs scraped and cups rattled as Joe and Abe got up from the table. Hoisting suspenders over damp shirts and grabbing jackets, they tucked the food into their pockets and stomped out the door.

“Come out from there now, you little monkeys,” Visha said. The blanket flew back and Rachel scrambled up, followed by Sam. Visha gave them each a kiss on the head, then Sam grabbed his sister’s hand and pulled her out of the kitchen and down the hall. While they took their turns at the toilet, Visha made a second pot of tea, refilled the kettle, rinsed the teacups, and put them back on the table.

When the children raced into the kitchen, Visha caught Rachel and lifted the girl onto her lap while Sam stood on his toes to reach the washbasin in the sink. He was tall already for a boy of six and seemed to Visha a small version of the man he’d one day become. His light brown hair was Harry’s for sure, as were the pale gray eyes that made Visha’s father doubt Harry was really a Jew. But where Harry was smooth and sweet-talking, Sam was sharp and quick, already getting in fights at school and tearing his pants playing stickball in the street.

Rachel put her hands on Visha’s cheeks to get her mother’s attention. Visha gazed at her reflection in her daughter’s dark eyes,

so brown they were nearly black. When Sam was finished, Visha dragged her chair to the sink so Rachel could stand on it to wash herself. After both children were at the table sipping tea and soaking bread, Visha dropped a whole egg into the kettle to boil and went in to wake her husband.

His breath still thick from sleep, Harry murmured in Visha’s ear, “So, did we make a baby last night do you think?” Visha whispered back, “If we did, he’ll need a papa who’s a contractor, so get yourself out of bed already.” Visha came into the kitchen with a shy smile on her face, Harry following her.

“Papa!” Rachel and Sam chorused. Their father dropped his hands onto their shoulders and pulled them close so he could kiss both of their cheeks at once.

“You give him a minute of peace,” Visha clucked. She lifted the lid of the kettle to check on the bobbing egg while Harry went down the hall. It was a luxury this, every morning a whole egg just for Harry, but he said he needed his strength. If Visha had to get a bone with less meat for their soup or buy their bread already a day old to afford the eggs, well, it would all be better once Harry made good.

When he got back, Harry lifted Rachel onto his knee and took her seat. Visha put a cup of tea in front of him and some more bread, then fished out the egg with a fork and set it on Harry’s plate to cool. She leaned against the sink, her hand absently resting on her belly, watching her husband with their children.

“So, Sammy, what did you learn from school yesterday?” Harry hadn’t seen the children since breakfast the day before. He’d worked late, then gone directly to his Society meeting, coming home after even the boarders were asleep to whisper in Visha’s

ear. She used to resent these Societies of his, the dues so hard on their pockets, until Harry convinced her the Society would back him when he went into business for himself.

Sam squinted. “

B-R-E-D,

” he said. “

T-E

.”

“And what’s this?” Harry asked, looking at Visha with sparkling eyes.

“That spells

bread

and

tea,

Papa! We learned the whole alphabet already, and now every day we learn spelling for new words.

C-A-T

. That spells

cat,

Papa!”

“Already such a genius,” Harry said, rolling his egg on the plate to shed it of its shell. Sometimes he saved a bite for Rachel, pushing the rounded egg white between her lips with his finger, but this morning he popped it whole into his mouth.

“What are you cutting today, Harry?” Visha asked. Rachel echoed her mother. “Yes, Papa, what are you cutting?”

“Well,” he said, addressing himself to his daughter, “we got patterns for the new shirtwaists yesterday, and I had to figure how to lay them out. The contractor, he likes my cutting because I don’t leave much scrap, but the material for the new waists has a little stitching running through the weave, and I had to lay out the pattern so the little stitch matched up at all the seams. It took me some time, that’s why I missed supper last night.” He glanced at Visha. “But I got it all figured out, so today I do the cutting.”

“Can I be a cutter, too, when I grow up?” Rachel asked.

“What for you want to work in a factory? That’s why I work so hard, so you don’t have such a life. Besides, girls aren’t cutters. The knives are too big for their little hands.” Harry put Rachel’s fingers in his mouth and pretended to chew on them until she laughed.

Harry turned to Sam. “You’d better get going now, little genius, or you’ll be late for school.”

Sam jumped up from his chair and dashed into the front room to dress. When he returned, Visha handed him his jacket. “And don’t waste the whole lunch hour playing in the street, come straight home to eat!” she called as he banged out the door and clattered down the two flights of stairs.

Visha went into the front room to open the windows. The April morning was clear and fresh. Leaning out, she saw a policeman still wearing his influenza mask, but Visha felt they were safe, now the winter was over. She knocked on wood as the grateful thought passed through her mind. Then she saw Sam burst from the front of the tenement, dodging vendors’ carts and motorcars and the milk truck’s old horse. It amazed her that such a small boy could charge so headlong into the world.