Other Women (3 page)

Authors: Fiona McDonald

For the kings of Europe from the Middle Ages right up until the late nineteenth century, it was a common custom to take at least one mistress, if not more, as a social, intellectual, romantic and sexual alternative to the legally wedded wife. Sometimes the arrangement suited both the king and his spouse: if the marriage had been made for political, economic or social reasons then the less sex she needed to have with him the better. Mostly the situation arose without any concern for the feelings of the wife, who was used as a breeding machine to bring forth the essential royal heir. This is not to say that there were no royal marriages in which the spouses didn’t come to love each other. Charles I and his wife were such a pair; lovers as well as a diplomatic union.

For a woman chosen to be the mistress of a monarch or man in a high position it was an opportunity to influence decisions of state, to have a say in a normally male-dominated world. She could enjoy certain social freedoms, have stimulating intellectual conversations with men of letters and the arts, and could access all sorts of secrets of state.

Who were these women and what backgrounds did they come from?

There were those who were born with the right credentials, for instance the Boleyn sisters whose father was Thomas Boleyn, Earl of Wiltshire, Earl of Ormond and Viscount Rochford. Their mother was the daughter of the 2nd Duke of Norfolk. Mary was one of Henry’s mistresses, a position later filled by her sister Anne. Anne’s parentage was of sufficiently high social standing as to not be an impediment to the king eventually marrying her (there were, however, plenty of other reasons that were put forth).

One of Charles II’s long-term mistresses was the actress Nell Gwyn. Her origins were not only obscure but were very low down the social scale and not of any social consequence. Therefore, even without the problem of there already being a queen at Charles’s side, she would never have been considered marriageable, no matter how deeply the king loved her.

Nell’s status was so unimportant that when the king tired of her he had her installed at a house belonging to the Crown but to which she was only a lessee. Nell indignantly asserted herself and demanded the title of the property be made over to her. The sole survivor of Nell’s two sons by the king, and named Charles in his honour, was given the title Earl of Burford, later to become the Duke of St Albans.

There are too many stories to tell in this book about all the mistresses to all the kings of England. Added to this, there are even more intriguing stories about mistresses to monarchs across the sea. This short list identifies some that might offer enticing stories for further study:

E

NGLAND AND

S

COTLAND:

Rosamund Clifford

(before 1150–

c

.1176), also known as ‘Fair Rosamund’ or ‘the Rose of the World’, was mistress to Henry II.

Agnes Dunbar

was mistress to David of Scotland from 1369–71.

Alice Perrers

(

c.

1340–1400), mistress to King Edward III.

Elizabeth ‘Jane’ Shore

(

c.

1445–

c.

1527), one of many mistresses to Edward IV and later to several other men.

Elizabeth Blount

(

c.

1502–39/40), one of Henry VIII’s long-term lovers and one he did not attempt to marry.

Mary Boleyn

(

c.

1500–43), the first of the Boleyn sisters to become mistress to Henry VIII.

Anne Boleyn

(

c.

1501/07–36), the second sister to become Henry VIII’s mistress and later his wife.

Elizabeth Hamilton, Countess of Orkney

(1657–1733), mistress to William III and II of England and Scotland from 1680–95.

Elizabeth Villiers

, mistress to William III.

Arabella Churchill

, mistress to James II.

Catherine Sedley

, mistress to James II.

Ehrengard Melusine von der Schulenburg

(1667–1743), mistress to George I.

Henrietta Howard, Countess of Suffolk

, mistress to George II.

Mary Scott, Countess of Deloraine

(1703–44), mistress to George II.

Amalie von Wallmoden, Countess of Yarmouth

, mistress to George II from the mid-1730s to 1760.

Elizabeth Conyngham, Marchioness Conyngham

, mistress to George IV.

Dorothy Jordan

, mistress to William IV while he was the Duke of Clarence. They were together for twenty years and had ten children.

Lillie Langtry

, mistress to Edward VII.

Daisy Greville, Countess of Warwick

, mistress to Edward VII.

Lady Jennie Churchill

(1854–1921), mistress to Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, later Edward VII.

Lady Frances ‘Daisy’ Brooke

, later Countess of Warwick (1861–1938), mistress to Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, later Edward VII.

Alice Keppel

(1869–1947), mistress to Edward VII.

Wallis Warfield Simpson

, later Duchess of Windsor (1895–1986), mistress then wife to Edward David, Prince of Wales, King Edward VIII, later Duke of Windsor.

E

UROPE:

Agnes Sorel

(1421–50), mistress to King Charles VII of France.

Louise de la Valiere

, mistress to King Louis XIV of France from 1661–67.

Anna Mons

, mistress of Tsar Peter the Great from 1691–1703.

Madame Du Barry

, mistress of Louis XV of France.

Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour

, mistress of Louis XV of France.

Eliza Rosanna Gilbert, later Countess of Landsfeld

, Irish dancer with the stage name ‘Lola Montez’, mistress of King Ludwig I of Bavaria.

Maria Antonovna Naryshkina

(1779–1854), a Polish noble who was mistress to Tsar Alexander I of Russia for thirteen years.

Magda Lupescu

, mistress to King Carol II of the Romanians.

Marie, Countess Walewski

, a Polish noble who was mistress to Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte.

Caroline Lacroix

, mistress to Leopold II of Belgium.

Baroness Mary Vetsera

, mistress to the Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria (1871–89). Vetsera never had the opportunity to become the wife of Rudolf because they were found dead together in his hunting lodge. It was thought that it was a suicide pact. However, there are other theories …

DITH THE

F

AIR

One of the earliest mistresses to be noted in English history may not really qualify for that title. Her name is Edith the Fair (

c.

1025–

c.

1086)

and there are various versions of the spelling of this ancient name. She has also been called Edith Swan Neck and Edith the Gentle Swan. To say she was Harold Godwinson’s mistress is probably to misunderstand the law and customs of the time in which they lived. As descendants of Danes they tended to hold on to traditions that had been brought from that country. One of these was handfasting, a commonly practised form of marriage. It was considered a legal form of marriage and the children from such a union were not seen as illegitimate. However, it was not seen as a proper marriage in the eyes of the Church.

Edith was born around

AD

1025 and had been married to Harold II for a good twenty years before he died. They had five children that are known of: three boys – Godwin, Edmund and Magnus, and two girls – Gunhild and Gytha. Gunhild went into the convent at Wilton; Gytha married Vladimir Monomakh, Grand Duke of Kiev. She was always considered to be of royal stock.

Edith possessed land in her own right and is thought to be one of the earliest owners of Sheredes and Hodders Danbury Manor. It was here that Harold was supposed to have spent a last night with his wife before he went to battle with William the Conqueror.

Some time before Harold’s last stand, he was fighting the Welsh under their leader Gruffydd ap Llewelyn. Harold was victorious and as part of a plan to unite Wales and Mercia, tying them to England, he took Llewelyn’s widow, Ealdgyth, to be his queen consort by marrying her in church and in the sight of God. Why he had never married Edith in a church ceremony is not known; perhaps the two felt it was not necessary as they were bound together by their handfasting ceremony. Certainly Harold’s second marriage was not made through love, although several accounts tell of Ealdgyth’s incredible beauty. Rather, the marriage was a political device that meant it would be easier for Harold to control his former enemies. Ealdgyth was nothing more than a token to seal a bargain – and her thoughts and wishes did not come into it.

When Harold was killed at the Battle of Hastings his body was badly mutilated. The clerics sent to recover it could not identify it so, as the legend goes, Edith the Fair, Harold’s long-time partner and the mother of his children, strode through the blood and gore and identified him by marks on his chest that were known only to her (romantic speculation claims they were the scars of love bites). Harold’s queen, Ealdgyth, was collected by two of her brothers, who presumably took her back to the heart of her home and people.

HE MISTRESSES OF

K

ING

C

HARLES

II

The seventeenth century was notable for the commonality of keeping a mistress, whether it was due to a craze or because Charles II made it fashionable. In fact, it was almost a social requirement that a gentleman have a long-standing liaison with a woman who was not his wife. Apparently Francis North, Lord Guilford was a gentleman who was considered to have neglected his duty by not keeping a mistress.

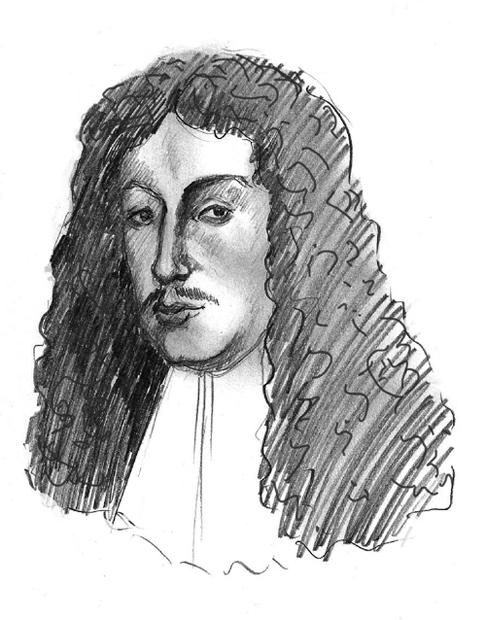

Charles II

HARLES, THE MAN

If a monarch is born under the star of Venus is it any wonder that he often falls in love with beautiful women? King Charles II was born on 29 May 1630 under such a constellation and he certainly made it his business to love women.

Charles II had no children with his wife, Catherine of Braganza. She suffered several miscarriages and stillbirths. In spite of the fact that Charles had sired a number of illegitimate children with various mistresses, England’s throne was to be handed to Charles’s brother James upon the king’s death.

HE MISTRESSES

Lucy Walter

Lucy Walter (

c.

1630–1658) is considered to be the first in a long line of Charles II’s mistresses. She is the first to have had a child that Charles admitted as his own. Unfortunately, Lucy came into Charles’s life when it was in turmoil. His royal father had been beheaded and he was in exile himself, and lacking regular funds. His attempt to win back the kingdom cost all of the money that his loyal supporters could scrape together; there was nothing left over with which to indulge a young woman with no dowry. Consequently Lucy’s life as the would-be king’s mistress was not a secure one and, when Charles went away on campaigns, Lucy was left without a provider. This meant that she was tempted to take other lovers, which did nothing to ensure trust and loyalty from Charles (he was not crowned king until 1661, long after his relationship with Lucy had fallen by the wayside).