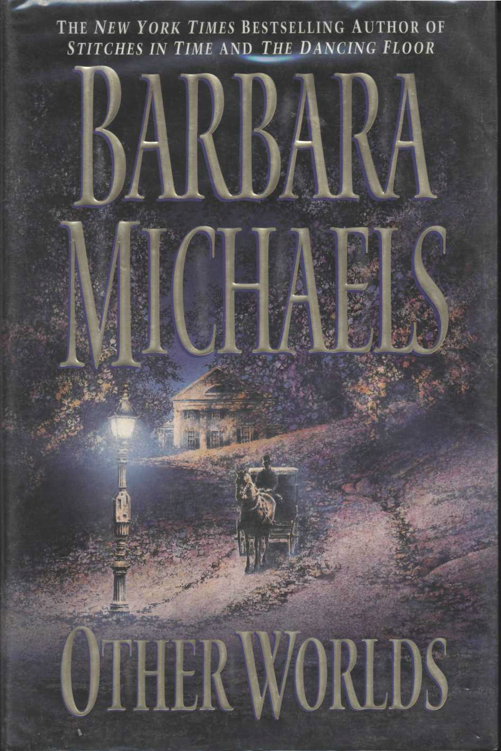

Other Worlds

Authors: KATHY

The First Evening

The scene

is the smoking room of an exclusive men's club, familiar through film and fiction even to those who have been denied admittance to such precincts because of deficiencies of sex or social status. The lamplight glows on the rich rubbed leather of deep, high-backed chairs. Grave, deferential servants glide to and fro, their footsteps muffled by the thick carpet. The tall windows are draped in plum-red plush, shutting out the night air and the sounds of traffic on the street without— the traffic, perhaps, of hansom cabs and horse-drawn carriages. For this is no real establishment; it exists outside time and space, in the realm of the imagination—one of the worlds that might have been.

A small group of men enters the room. They have the sleek, satisfied look of gentlemen who have dined well, and who are looking forward to brandy and a fine Havana and another pleasure equally as great—conversation with their peers on a subject deeply engrossing to all of them.

One man leads the way, striding impatiently. His high forehead is wrinkled, his eyes narrowed. Mr. Frank Podmore calls himself "skeptic-in-chief" of the Society for Psychical Research.

The spiritualist tricksters he has exposed, and many of his own colleagues in the SPR, consider him unreasonable and unfair. Those colleagues would recognize the expression on his face this evening. Podmore is on the trail again, ready to pour the icewater of his doubt on another questionable case.

Behind him comes a man whose voice still retains the accents of his native Vienna—Nandor Fodor, formerly director of the International Institute for Psychical Research, who resigned in disgust when his colleagues objected to his "filthy-minded" explanations of certain cases. A practicing psychiatrist for many years, he has investigated almost as many purported "ghosts" as has Podmore.

The third member of the group is stocky and clean-shaven, with keen blue-gray eyes. Born Erik Weisz, son of a Hungarian rabbi, he is better known as Harry Houdini. Many of the spiritualists he ridiculed claimed that he himself must have had psychic powers in order to accomplish his amazing feats.

One of his old antagonists, a burly man with a bristling mustache and soft brown eyes, walks with him. Conan Doyle and Houdini broke off their friendship when Houdini attacked Doyle's faith in the survival of the dead. It would be pleasant to believe that in some other time and place these two good men have at last made up their quarrel.

A fifth person follows modestly behind the others. From his hesitant manner and the formal way in which the others address him, one might deduce that he is a guest, rather than a regular member of the group. He is taller and heavier than the others; his evening suit is a trifle old-fashioned and more than a trifle too small. He has very large feet.

They settle into their chairs. Topaz liquid swirls in the bell-shaped glasses and a fragrant fog of smoke surrounds them.

"Well, gentlemen," says Podmore, "are we ready to begin?"

Typically, he does not wait for a reply, but continues, "Tonight's case—"

Doyle raises a big hand. "Always impatient, Podmore. Don't you think we owe our guest a word of explanation first? He knows our purpose, but cannot be familiar with our methods."

"Oh—certainly." Podmore turns to the stranger. "I beg your pardon, sir. All of us have investigated many cases of presumed supernatural activity, some as agents of the SPR and some, like Houdini, in a private capacity. During our evenings together we enjoy a busman's holiday, applying our combined expertise to the investigation of famous cases that have never been satisfactorily explained. Sometimes we agree on a solution; more often we agree to disagree."

"More often?" Fodor repeats, smiling. "I cannot remember an occasion when the verdict was unanimous, and I know none of you are going to agree with my solution to this case. The Bell Witch, is it not?"

"Correct," says Podmore. "And, as is fitting, we have selected our American member to describe this American ghost. No more interruptions, gentlemen, if you please; pray, silence for Mr. Harry Houdini."

Houdini has his notes ready. He gives the others a rueful smile. "This is worse than escaping from a sealed coffin, gentlemen. Book research isn't my style, and this is the first case I've investigated where all the suspects have been dead for over a century. But as Podmore would say, that just makes it more challenging. And what a tale it is! Dr. Fodor here has called it the greatest American ghost story. I would go further; I would call it the greatest of all ghost stories. There is nothing to equal it on either side of the Atlantic.

"Over the years the true facts have become so encrusted with layers of exaggeration, misinterpretation, false memories and

plain out-and-out lies that the result sounds like one of Sir Arthur's wilder fictions. Our greatest difficulty will be to figure out what really happened. I won't presume to do that; I will just give you the story as I have worked it out and let you decide what is important and what isn't. Ready? Then here we go."

Betsy Bell

was twelve years old when the witch came. It sounds like the beginning of one of the fairy tales beloved by juvenile readers, a tale in the great tradition of the Brothers Grimm. Even the name of the heroine conjures up the image of a smiling, dimpled child with bows on her pigtails, skipping merrily through the woods with a basket on her arm!

But Betsy's witch was no Hallowe'en hobgoblin with a pointed hat and a broomstick, and by the time it finally left the Bell household, Betsy was a young woman of seventeen who had seen her lover driven away and her father tormented into his grave. Betsy is certainly the heroine of our tale—a tale of horror so fantastic no writer of fiction would dare invent it. But she is not the chief protagonist. That distinction belongs to another character.

In the early part of the nineteenth century, Robertson County, Tennessee, was being settled by easterners looking for new land. It was not wild frontier country; the only Indians in the region were those whose dry bones lay buried in the grassy mounds scattered about the countryside. Most of the settlers were well-to-do farmers and slaveowners. The little community was civilized enough to possess a school, presided over by a handsome young

master, and several churches. The oldest of these houses of worship, the Red River Baptist Church, had been founded in 1791. Some of the settlers belonged to this church, some to that of the Methodists, but petty sectarian differences did not divide them; an admirable spirit of Christian tolerance prevailed.

The country these men and women discovered was a lovely land of rolling hills and stately forests, of fertile meadows and rippling streams—an abundant land, giving freely of its riches. Game abounded in the woods, the virgin soil provided grain and vegetables, maple syrup flowed from the trees, and fish fairly leaped out of the river to snatch the angler's hook.

Into this earthly paradise, in the year 1804, came Mr. John Bell and his family. John and his wife, Lucy, were from North Carolina. Mrs. Bell, a good Christian woman, had obeyed the Biblical injunction to be fruitful and multiply. By 1804 she had given birth to six children.

The size of their growing family and the urgent invitations of friends who had already settled in the west convinced Mr. Bell to emigrate. He sold his farm in North Carolina for such a good price that he was able to buy a thousand acres of land in Tennessee, along the Red River.

There was a house on the property, built of logs and covered with clapboard. It was one of the finest homes in the county, with six large rooms and a parlor, called a "reception room" in those days. An "ell," or wing, contained several more rooms and a passageway. A wide porch stretched across the front of the house, looking out over a vista of green lawns shaded by fine old pear trees. It must have been a pleasant place to sit on spring afternoons, when the trees were masses of snowy blooms, and the Bells welcomed visitors hospitably. John Bell made his own whiskey of pure spring water, and I assure those of you who have not tried it that there is no finer beverage. Drunkenness

was a sin, of course, but there was nothing wrong with an occasional nip, "to sharpen one's ideas."

With the help of his neighbors the industrious Mr. Bell cleared more land and built barns and slave quarters. Soon after they arrived Mrs. Bell had another child—a daughter, who was named Elizabeth. Two more children followed in due course. By the fateful spring of 1817 only one of the Bells' offspring slept in the family cemetery on the gravelly ridge behind the house, his grave shaded by cedar and walnut trees. One out of nine is an amazing survival record for that time; perhaps the healthy life and the clean country air had something to do with it. Cynics might claim that the absence of medical attention also helped, but this would not be entirely accurate. The community possessed several doctors, one of whom, Dr. George Hopson, attended the Bells in cases of severe illness. We will meet Dr. Hopson in due course, when he was confronted with a case that would try the skill of any physician.

Though we have been formally introduced to Mr. and Mrs. Bell, we do not know them well. In attempting to sketch their portraits we suffer from the commendable yet frustrating refusal of survivors to speak ill of the dead. No candid comments have come down to us, no faded photographs survive; we can only sketch verbal portraits, vague and incomplete. Yet by piecing together a fact here and a casual comment there, we can derive some notion of what the actors in this eerie drama were like.

Simple arithmetic tells us that if John Bell was born in 1750 (which he was), he was sixty-seven years of age in 1817, when the trouble began. Despite his age, he was as hale and hearty as many a man twenty years his junior. (Bear in mind, my friends, that his last child had been born when he was sixty-two.) Unlike the aristocratic planters of the southeastern states, the Washingtons and Jeffersons and Lees, Mr. Bell was no gentleman of leisure, but a

farmer who worked with his own hands. His children praised him as God-fearing and industrious, sober and devout. We need not take these epitaphs too literally, but we must admit we know nothing to his discredit. If his children fail to mention laughing and romping with their father, they are equally silent about harsh punishments. He was certainly a devout Christian; his was one of the homes in which weekly prayer meetings were held. Yet it would be a mistake to picture this patriarch as a dour Puritan. He had at least one amiable human quality—he was not stingy with his whiskey

Lucy Bell, affectionately known to her friends as "Luce," was approximately fifteen years younger than her husband. Her children had not acquired the now-fashionable habit of blaming all their troubles on their parents; they spoke of Lucy with the highest praise. She was, simply, the best woman living. Many years later Richard Williams Bell wrote of his mother that she was "greatly devoted to the moral training of her children, keeping a restless watch over every one, making sacrifices for their pleasure and well-being." A curious word to choose—

restless.

But perhaps Richard only meant untiring.