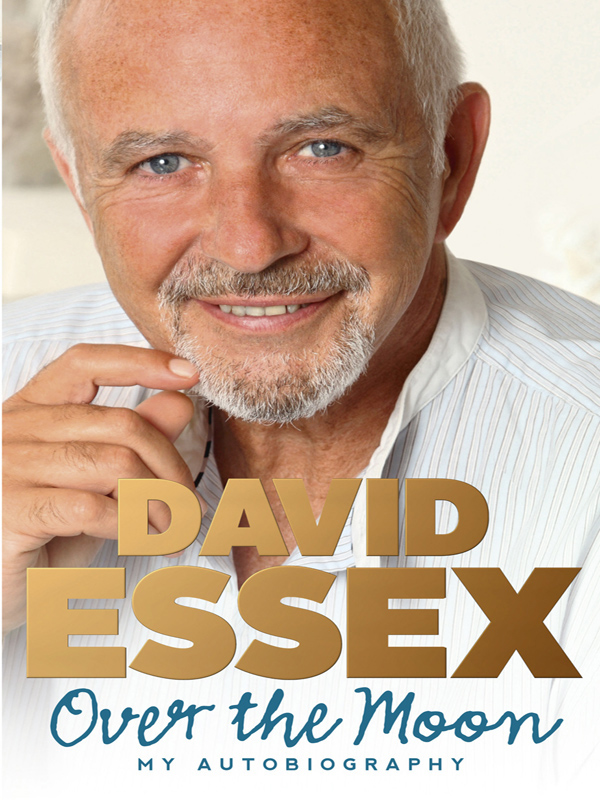

Over the Moon

Authors: David Essex

Introduction: From Jesus to Eddie Moon

1. You Can Take the Boy Out of the East End…

2. Getting in Trouble and Blowing Bubbles

3. Sex, Drums and Rock ’n’ Roll

4. The Smashing of the China Plates

5. Oh My, Thigh High, Dig Dem Dimples on Dem Knees

6. Luvvies, Gangsters and Snogging Brown Bears

11. ‘It’s Because We F****** Love You’

15. My Life as an International Drug Smuggler

18. What Shall We Do with the Drunken Sailboat?

19. Two Heads are Better Than One

20. A Lot of Work for Charydee

21. It’s Always About the Family

25. You Can Put the Boy into the East End…

About the Book

‘You get a few – very few – moments in your life when suddenly something happens and you know immediately that things will never be the same again. I had such an epiphany. I was thirteen on an undercover schoolboy mission to explore Soho, when we heard some killer music coming out of a club. What I found in there altered everything I felt and knew about myself, and about my future. It rearranged my very DNA.

The band playing on stage completely blew me away. The atmosphere and energy were just incredible. I would never have thought it possible, but suddenly I couldn’t care less about the West Ham youth team or becoming a footballer.

This was rhythm blues as it should be played: rich and strong and loud and powerful. It seemed to touch my very soul. I wanted to be a part of it. Yes – the drums. They were the foundation, the rock for this thrilling, explosive racket. That was my future settled, then: I was going to be a blues drummer…’

Well, that’s how it all started. But the future held crazy, unimaginable fame and undreamt of adventure for David Essex. From

Godspell

to

EastEnders

, it’s been an amazing life. And here is the full, incredible story – in his own words.

FROM JESUS TO EDDIE MOON

The writer F Scott Fitzgerald said there are no second acts in American lives. I guess I must be lucky I’m British, then, as I reckon by now I have been through acts two, three, four and five and must be on the encore.

I recently spent five months on

EastEnders

playing that lovable rogue with a dark past, Eddie Moon. It was a privilege to be part of one of the biggest shows on British TV and I had a fantastic time making it. People seemed to take to Eddie, and I guess for a lot of people under thirty, that will be what they think when they see me now: Eddie Moon.

For people a little older than that, however, it is a different story entirely. They may well focus on one of my many incarnations in the past. Maybe they will remember me as Jesus, or at least his human form on earth, when I first emerged from obscurity in the musical

Godspell

all those years ago.

They might, however, prefer to think of David Essex the singer and songwriter, the pop star with the mop of gypsy curls who enjoyed a string of chart-topping hits and who for a while seemed to be on the front cover of

Jackie

magazine every week.

I

know for some folk, I will forever be the smiling waif who sang ‘Rock On’ and ‘Hold Me Close’.

Maybe others will always see me as Jim MacLaine, the angst-ridden anti-hero of the movies

That’ll Be the Day

and

Stardust

, the working-class boy who longed to be a rock star and found fame and fortune only for them to destroy him. Jim seemed to leave a mark on a lot of people: he certainly left one on me.

I’ve been told by some people they will always think of me as the iconic revolutionary, Che Guevara, who had so much impact when I played him on stage in Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s

Evita

. And for a few, I will always be the amiable lock-keeper with a dodgy past from TV show

The River

.

I think I have had quite a life – or quite a few lives – to date. I have written West End musicals, scored ballets and even (don’t laugh) starred in a ninja action movie. And that’s before we even mention the pantomimes, a novelty single and a

Carry On

film (yes, really) in my early years.

So a lot happened before I spent a while as Eddie Moon, and now feels like the time to reflect and tell my life story. I think it’s a fairly extraordinary tale, and it began in a post-war East End district that was every bit as poor as Walford: a place called Canning Town.

YOU CAN TAKE THE BOY OUT OF THE EAST END…

OVER THE YEARS

, people have made a lot of my relatively poor background and impoverished upbringing, but it never felt bad to me. As a kid, what you know is all you know, and my life always seemed fine and dandy. I could not have had two more loving parents, and when I think back, I remember a very happy childhood.

I wasn’t quite a war baby but I wasn’t far off. I made my first appearance on 23 July 1947, at a maternity hospital in West Ham in the heart of the East End. Forceps were involved. I was a bit on the light side, at six pounds four ounces, and was yellow with jaundice, so I can’t have looked all that good.

I wasn’t David Essex in those days, of course. I was born David Albert Cook, to my two loving parents, Albert and Olive – not that anybody ever called her that. My mum was a petite woman, very beautiful and full of life, who looked a bit like a doll and so went by the nickname Dolly, and that was what everyone knew her as.

The three of us were very lucky to be around. My parents had an eventful war. My dad, who worked on the docks when

London’s

Docklands really

was

docklands, had been conscripted into the Royal Artillery when hostilities broke out. He was stationed on the big guns in Dover, and got posted up to Sunderland for a while.

My dad had to get a twenty-four-hour pass to marry my mum and it was the luckiest thing he ever did, in more ways than one. He turned up at the church on the back of his brother George’s motorbike as my mum waited for him in her BHS wedding dress. My dad’s battalion set sail for Norway without him: they got blown out of the water, with no survivors.

This wasn’t the only close call my dad experienced: the Germans scored a direct hit on his gun nest once, but he escaped with just a burn. As for my mum, living in the East End, she was exposed to the full horrors of the Blitz. One of the many times that the sirens sounded, she and her sister ran to a local school. They were turned away because the basement was full and fled to the tube station. The bombers scored a direct hit on the school.

Another time, Mum was walking in a country lane in Kent with her sister and niece when a Messerschmitt appeared in the sky and started machine-gunning them. They tried to escape down a manhole but couldn’t get the cover off so ran to a nearby house and banged on the door, screaming, with the pilot still firing at them. How can a human being do that: try to blow up two women and a little girl? Luckily, he gave up and flew off.

Remarkably, Albert and Dolly came out of the war in one piece, except for a bit of damage to my mum’s hearing, and set up home in a rented one-bedroom flat in Redriff Road, Plaistow. They were keen to start a family as soon as possible. Mum says

she

always knew she would have a boy and she was always going to call him David: maybe her gypsy roots gave her this inkling.

My mum was one of seven kids and her dad, Tom Kemp, was a gypsy. On her wedding certificate, it gave his job as ‘Travelling Tinker’. When he first came over from Ireland, he moved around the country and made saucepans. Sadly, I never met him: he died before I was born.

Tom had been married before, to a gypsy woman. When she died and Tom married my nan, Olive, his first wife’s mother came over from Ireland and stood outside Nan’s house, cursing her. Dressed all in black, she waved a silver sovereign necklace at her door and said she would never have a penny in the world. Co-incidence or not, that’s just how Olive senior’s life worked out.

From my parents’ accounts, I was a happy baby and toddler and spent my time pouring my food over my head and falling over. The problem was that our Plaistow landlord didn’t allow children in his flat, so Mum and Dad decided to move out and put our names down for one of the high-rise council flats that were replacing the bombed terraces of the East End.

This left us with nowhere to live in the short term, so we went to stay with my mum’s sister, Aunt Ellen, her husband Uncle Bob and my cousin Rose in Canning Town. Their council house had a small garden and they were gracious hosts but it was cramped with all of us there, and even though I was only two years old, I think I sensed we were in the way.

My dad was back on the docks by now, and every day my mum would take me out in my second-hand pushchair to get us out from under Aunt Ellen’s feet. We’d walk around

Rath-bone

Street Market in Canning Town, a hubbub of stallholders and shoppers that felt like the most exciting place in the world, or take our ration book to the butcher’s to get a few scrag-ends of meat.

This routine went on for a year, with the council showing no interest in offering us a home, so my parents tried to force their hand. After a brief family conference, it was agreed that Ellen and Bob would ‘order’ us to leave, and my dad would tell the authorities that we were homeless.

This plan backfired in a major way: the council put us into a workhouse.

I say workhouse, but a lot of people would call it a nuthouse. Forest House in James Lane, Whipps Cross was an institution for the homeless and the mentally ill. There was no room there for my dad, so he had to stay with his sister, Ivy, in Barking and pay the eighteen-bob-a-week rent for Mum and me to share a poky, curtained cubicle with a single bed and a cupboard.

Forest House was full of women and kids in the same desperate situation as us, crammed into tiny living units and all sharing one kitchen. Sixty years on, I can still picture the pink roses on the cubicle curtains, and remember the harsh smell of hospital antiseptic that lingered around its long cream corridors.

Forest House seemed massive to me, and as a wide-eyed kid I found it fascinating. It had a surreal, almost fairy-tale air. Troubled inmates trudged the corridors, singing to themselves. I got to know a few of them. One man asked me one morning if I would like some conkers, and returned that evening with a coal sack of them.