Panama fever (80 page)

Authors: Matthew Parker

Tags: #History - General History, #Technology & Engineering, #History, #Central, #Central America, #Americas (North, #Central America - History, #United States - 20th Century (1900-1945), #United States, #Civil, #Civil Engineering (General), #General, #History: World, #Panama Canal (Panama) - History, #Panama Canal (Panama), #West Indies), #Latin America - Central America, #South, #Latin America

Chamber cranes at Miraflores

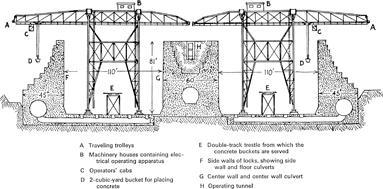

Spanning the site were four giant, 800-foot-long cableways, supported on either side of the great basin by towers 85 feet high. As each pair of buckets was filled with 6 tons of liquid concrete, the car moved off and was then picked up by a hook on the cableway and taken off to the site. At the same time, an empty skip returning from the site was set down on the railcar.

The system worked brilliantly. In one year a million cubic yards of concrete were delivered to be molded and set. The walls were built in 36-foot sections all the way to the top, which took about a week. Then the scaffolding, shutters, and cableway towers, all rail-mounted, were simply shifted along to the next section.

On the Pacific side concrete was batched on-site and lifted to the required position using a tower crane. Here even more concrete was used for the single lock at Pedro Miguel and the double tier at Mi-raflores. A small dam was also required at Miraflores in conjunction with the locks, forming the tiny Miraflores Lake, but this structure presented no serious difficulties.

The lock basins are the construction marvel of the canal. They are massive, a hundred thousand tons of concrete each, 1,000 feet long and more than 100 feet wide. Seen full of water they are impressive enough, but those who stood on the empty floor and gazed upward at the sheer, featureless walls, more than 80 feet high, taller than a six-story building, were awestruck. “These locks are more than just tons of concrete,” commented one such visitor, “they are the gate to that pathway of which Columbus dreamed and for which Hudson died. They are the answer of courage and faith to doubt and unbelief. In them are the blood and sinew of a great and hopeful nation, the fulfillment of ancient ideals and the promise of a larger growth to come … I left with the feeling that follows a service in a great cathedral.”

he mechanical marvel of the canal was the machinery of the locks. For one thing, the entire system was powered by electricity (supplied from the hydroplant next to the spillway), a great innovation at a time when steam- and horse-powered systems were the norm, and the electrification of factories was in its infancy. The power that did the hard work of lifting or lowering ships was, of course, gravity, the filling of a lock with water from the lake or a higher lock or the release of water to farther down the system. Water was drained or admitted through tunnels 18 feet in diameter, built lengthwise within the center and wide walls of the locks. Running perpendicular to these were smaller tunnels or culverts under the floors of the locks, fourteen per chamber. Each had five evenly spaced openings in to the floor, so that when water was admitted the turbulence would be minimized. The main culverts had large steel gates as valves. The principle was ancient: to fill a lock, the valve at the lower end would be closed and the upper one opened, and vice versa to drain it. Each lock had a lift of an unprecedented 28 feet, and the system aimed to raise or lower a ship this distance in just fifteen minutes.

he mechanical marvel of the canal was the machinery of the locks. For one thing, the entire system was powered by electricity (supplied from the hydroplant next to the spillway), a great innovation at a time when steam- and horse-powered systems were the norm, and the electrification of factories was in its infancy. The power that did the hard work of lifting or lowering ships was, of course, gravity, the filling of a lock with water from the lake or a higher lock or the release of water to farther down the system. Water was drained or admitted through tunnels 18 feet in diameter, built lengthwise within the center and wide walls of the locks. Running perpendicular to these were smaller tunnels or culverts under the floors of the locks, fourteen per chamber. Each had five evenly spaced openings in to the floor, so that when water was admitted the turbulence would be minimized. The main culverts had large steel gates as valves. The principle was ancient: to fill a lock, the valve at the lower end would be closed and the upper one opened, and vice versa to drain it. Each lock had a lift of an unprecedented 28 feet, and the system aimed to raise or lower a ship this distance in just fifteen minutes.

Worries voiced in the U.S. press prompted the adoption of a series of stringent safety measures to avert the worst-case scenario of a ship smashing through the upper lock, causing the lake to pour through the breach. No ship would pass through the locks under its own steam. Instead the movement of the ships would be controlled by a group of powerful electrical cars, mounted on rails at the lock's edge, each in control through a windlass, a steel cable, attached to the ship. Each lock had a double gate, and a chain ran in front of the mouth of the top lock to catch and slow any vessel approaching in a dangerous way. Failing that, an emergency dam could be lowered across the channel within minutes.

All of the mechanisms for the lock operation were controlled from one position, where a working replica of the locks had been made, with the controls for each machine adjacent to its model. In addition, a system of safeguards meant that it was impossible, for instance, to open a culvert valve if the relevant lock gates were not firmly shut.

The manufacture of the lock gates was the only substantial part of the canal work that was subcontracted. A Pittsburgh firm, McClintic-Marshall, started assembly and installation in May 1911 at Gatún, August at Pedro Miguel, and at Miraflores in September 1912. The lock gates were designed to close into a flattened V. When open they slotted into a recess in the lock wall. Each individual gate was 65 feet wide and 7 feet thick and varied in height from 47 to 82 feet depending on its position. The highest were the bottom gates at Mi-raflores, which had to cope with the Pacific tides. The gates were opened and closed by giant wheels within the lock gates. These needed to be hugely powerful machines, but the gates weighed less than they looked. They were hollow, consisting of steel plates riveted on to a steel frame, and watertight so relatively buoyant. At their base were rollers, which ran on enormous steel plates embedded into the floor of the lock.

Few ships at that time needed anything like the space the giant locks provided, so intermediate gates were installed so that vessels less than 600 feet long could pass through more quickly and with less expenditure of water. So in all there were forty-six pairs constructed and installed. The great steel gates were one of the most spectacular sights on the Isthmus, particularly while the lock chambers were still empty and their huge size could be appreciated.

However, the work on the gates also figures, along with the explosion at Bas Obispo, as the worst memory of the construction period for the West Indian workers. The money was good—McClintic-Marshall paid US$0.25 an hour, more than double the basic labor wage—but the work was among the most dangerous anywhere. As a West Indian work song from the time had it:

Yuh gets more money for that job than working in the cut

But it all depends muh honey on if yuh don't get hut

For if you ever get a drop yuh surely have to die

For dem gates lawd gad gal is seventy five feet high.

In mid-1912, when work on the gates was well advanced, Harry Franck went to the Gatún Locks looking for a man accused of theft. “I found myself racing across the narrow plank bridges above the yawning gulf of the locks, with far below tiny men and toy trains, now in and out among the cathedral-like flying buttresses, under the giant arches past staring signs of “DANGER” on every hand… I descended to the very floor of the locks, far below the earth, and tramped the long half-miles of the three flights between soaring concrete walls … On them resounded the roar of the compressed air riveters and all the way up the sheer faces, growing smaller and smaller as they neared the sky, were McClintic-Marshall men driving into place red-hot rivets, thrown at them viciously by negroes at the forges.”

This was the worst job of all. The riveters, using heavy pneumatic hammers, worked on scaffolding that normally consisted of chains running down the face of the gate to which hooked planks were attached one above the other. There were four men per plank, and any sudden movement could unbalance and unhook the platform; if one came down from above, it usually took a few lower ones with it.

Eustace Tabois remembered a particularly gruesome accident at Gatún. “We were working there one Sunday,” he said. “I was inside the gate, right at one of the portholes, and I just happened to look out. I saw a shadow come down like that. And when I look out I saw this man down below. The scaffold break away with him and he went right down and the plank down there with him a spike went right though his head. Kill him dead, kill him dead. Man used to die every day.” “Scuffles would break away,” said James Ashby, “hurting many and sometimes killing men instantly. Lord how piercing!” As another West Indian commented, “The family of those men working on those locks were always fearful as to who may be next to fall.”

It was the same on the Pacific side. Jamaican Nehemiah Douglas was working on the giant gates at Miraflores when the cable holding his plank broke, “kill[ing] some men, on the spot. The amount of blood that flowed gave the appearance of a little gully,” he later wrote, “and when I saw what appeared to be an island of blood, I got nervous, I think, because how I got down, I do not know; but I got down and ran like never run before, straight home in Paraiso.” Many stayed away after witnessing incidents like this, even if they had pay to collect, but Douglas returned and was soon after hit by a crane and received a fractured skull.

Nevertheless, with the money that could be earned, men still “poured like sand” to go and work on the locks. However many were injured or killed, “there were always others to take their places without hesitation.” This became more urgent as the project progressed. It was obvious that the well-paid work was not going to be around for that much longer. The canal project was now nearing its triumphant conclusion.

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

THE LAND DIVIDED, THE WORLD UNITED

During the four last years of construction, nearly 100,000 American and European visitors arrived in Panama to view work on the canal. Interest was so great that steamship lines diverted vessels from other routes to the Caribbean. At Ancón the Isthmian Canal Commission created a tourist station with a lecture room, relief maps, and models of the locks. Tourists could also visit the work site by taking a special train whose open sightseeing cars had been converted from Panama Railroad flatcars.

Back in the States, Tin Pan Alley was busy churning out hits such as “Where the Oceans Meet in Panama (That's Where I'll Meet You)” and “The Pamela,” and the press eagerly reported, alongside sombre news of rising tensions in Europe, each and every landmark and breakthrough.

Work on the west breakwater from Toro Point in Limón Bay started in 1910. As the local rock was too soft to withstand the power of the “northers,” 12- to 18-ton rocks were blasted from the quarry in Portobelo and shipped by sea to be dumped by barges along the outside of the breakwater line. Then a series of creosoted piles were driven in to form a trestle on the inland side. Next, local stone was loaded into flatcars, pushed out along the trestle, and unloaded by the plow method on the inside of the line of hard rock. Work progressed steadily and Colón became a safe harbor for the first time. The east breakwater caused more problems, mainly because the French had dredged deep channels across its line, but it was completed in 1915. The digging inland did not all go smoothly. At Mindi huge amounts of explosives were required to break up the rock, and there were constant problems from flooding. However, by the summer of 1912 only a small belt of land 1,000 feet wide separated the open Atlantic channel from the site of the Gatún Locks. By August 1913 it was the same at the other end of the canal, with just a dike holding the waters of the Pacific back from the Miraflores Locks.