Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind (3 page)

Read Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind Online

Authors: Sarah Wildman

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Cultural Heritage, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Jewish

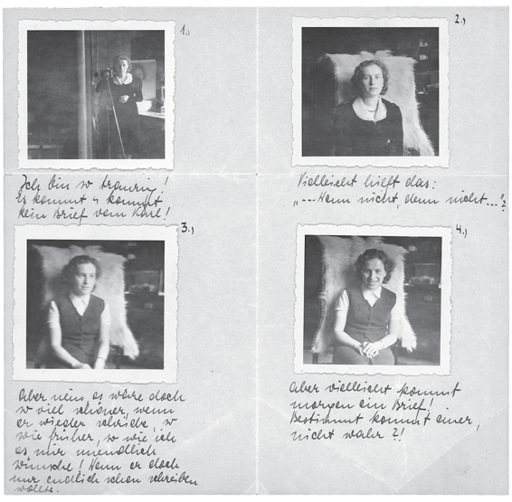

The little note was dated May 5, 1939, about ten months after my grandfather had left Europe.

I held the document up and asked my grandmother who the author was. “Your grandfather’s true love,” she said, and offered nothing more.

His what?

My grandmother was not a terribly romantic woman. What a totally peculiar, what a totally devastating thing to say. I tried to press her on it, but she demurred and retired to her room. She refused to comment further; I feared to ask more.

Back at home, I called my grandfather’s sister, Cilli. “Who was she?” I asked.

Ah, Valy,

she said, with a sigh, and a moment’s hesitation. Valy and

Karl, she explained, studied at the University of Vienna’s medical school together. Valy had been desperately in love with him for years, and he had barely noticed her. That lopsided relationship remained true until one summer, partway through his medical degree, when he ran to find her at home—she was from Czechoslovakia—and professed his love for her as well. They had had a few years together. And then he’d escaped to New York. She stayed behind. “She was brilliant. Brilliant! A wonderful girl.”

Vonderful

.

Later that week I ran into a prominent Jewish intellectual. Breathlessly I told him of my find:

My grandfather had a lover, he’d left her behind, and

who knew what happened

.

Maybe there was a woman to be found out there, maybe . . .

“Someday,” he said, barely looking up, “you’ll pass through Berlin or Vienna. And you’ll fuck some German. And then you’ll write your story.”

Crushed, I thought,

Oh God, this intrigue, this intensity; it’s all so horribly banal.

Of course there are these Holocaust stories, of course there were lovers left, of course lives were rerouted, uprooted, destroyed. What new story would I find, really? What more was there to say?

Cilli wrote to me that week. She sent the note by regular mail, to my office. “Maybe you’ll write the story of Karl and Valy,” she typed, “maybe you’re the one to tell it.”

But I had already stopped digging.

One after the other, my great-aunt, and then my grandmother, died. I had failed to ask more questions, even though I wondered, often, if there was more to the story of the girl in the photographs. I assumed if there was more to know, it had been thrown away, purposely or not, destroyed by my grandmother in her purge of my grandfather’s documents. Later, much later, far too late, I went back and listened to an interview I had conducted with Cilli for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in the months after I graduated from college. Valy was everywhere in her memories, but I hadn’t yet known to listen for her.

“He had a girlfriend who he went to medical school with, she was very bright, and very short, and she was so much in love with him!” Cilli said that long-ago December afternoon. “She would wait every night—until eleven or twelve—while he was out giving lessons to students. She was from Czechoslovakia. . . .” And then, later, the tape mentions her again: “He was making plans with Valy to run away from Austria—this girlfriend—he knew as a foreigner he could not open a medical office in Vienna. Then, instead, he ran away with us.”

These sentences hang there on the recording, ready for a

follow-up. But each time I listen to it, the outcome is the same: I do not press her to explain further when I hear the name Valy. I do not follow up. Instead, I focus, exclusively, on the five who left—my grandfather, his mother, his sister, his brother-in-law, his nephew—and I push past references to those who did not leave. I was so sure, then, of the important story, so sure of the supreme veracity of what I already held to be true. Now when I listen to the tape, I am haunted by what I might have asked.

But that’s now. For a long time, even after I found her photos, and her small notes—even after I knew to wonder about her, when I thought about her, I simply assumed Valy, too, was dead, or, at least, disappeared; a sad, personal addendum among six million catastrophic tales. I didn’t even Google her. I simply left it alone. Yet every now and then I wondered: I worried something was missing, some aspect of the grandfather I’d worshipped had been doubly lost by not pursuing the story; I wondered, too, if she somehow might have actually survived.

Instead of writing about my own family, I began writing about the other addenda—the small Holocaust stories, little pieces of the puzzle—investigating the narratives at the edges, stories that asked questions of what happened to regular people, the minor stories, the warp and weave of the tragedy.

I didn’t find out what was missing for nearly a decade. By then I’d spent some years out of the country, always, quietly, in the back of my mind, searching—though for what, I couldn’t have told you. Part of it, I told my closest friends, was an endless foray into my own identity. It felt so arbitrary to be American. If I could better understand my grandfather’s story, I kept thinking, as I spent month after month in Europe, I might discover why I could never feel settled, or fully happy, at home, why I felt most alive in transit, moving. A wandering Jew! Just like my grandfather, who fled Europe and then, it seemed, remained on the road for years after. He and my grandmother

traveled endlessly: all across Europe, of course, but also China (just after Nixon), Morocco, over the Atlas Mountains (by car), Hungary, Russia, Peru, Argentina, Ecuador, Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, Japan, Israel. I would receive dolls from their journeys, hard-faced toys that weren’t meant for play. Stiff geishas in kimonos, with real hair. A Native American woman, doomed to weave her loom forever. A Nordic-looking Swiss mountain lass with eyes that blinked and a stiff crinoline beneath her traditional gown. My sister and I lined them on the shelves in our childhood bedrooms, kept them as dusty reminders of the exotic life my grandparents led.

Karl and Dorothy Wildman in Switzerland, early 1970s. At some point in his life, he changed the spelling to Carl.

The more stories I wrote on the period, the more people I met who were grappling with questions of identity—Jew, Austrian, German, Pole—and the more I came to believe that if I was persistent enough, I might discover where my generation—and I—fit into the picture. We were shaped by the stories our grandparents had told us, or not told us, deeply affected by them and yet distanced, unable to figure out how to translate them for our own children and the children yet to come, unable, in some ways, to decide how to talk about this history once the eyewitnesses were gone. The stories were tactile and yet dusty, faded; they were real, and yet totally unfathomable. And if they felt this way to us, what would they feel like to those who came after? We are the last to know and love survivors as who they are—as human, as flawed, as our family. What, now, do we do with that knowledge?

Even as I researched the history of others, I assumed my understanding of my grandfather’s story—as well as my knowledge of the sweet girl in the photos—was doomed to remain wholly incomplete.

But then, toward the end of the aughts, something changed. As my parents prepared to sell my grandparents’ house, packs of family members visited, culling through papers day after day, selecting, from the acquired detritus of two lives. There wasn’t much, there was too much: it was treasure; it was junk. I filled a bag with dresses that had belonged to my great-grandmother from the 1920s, my grandfather’s Army-issue pants (he volunteered in 1942 and emerged, after several promotions, as a major three years later), and his University of Vienna medical diploma, stamped with the Nazi insignia.

All the items deemed worth saving were collected and bundled into boxes and brought to basements in New Jersey and New York, where they were promptly forgotten again. Mostly. The ones in my parents’ home remained endlessly tempting to me, so much so that, on a visit home a few months later, I couldn’t resist and took one apart. It was labeled “C. J. Wildman, Personal,” C.J. being the initials for Chaim Judah, my grandfather’s given name. Tucked inside was a music box I remembered from childhood, an Alpine house whose roof opens and plucks notes of some long-forgotten Swiss folk song. Next to it, I discovered another carton labeled “Correspondence, Patients A–G.”

It was a wide file box with a small metal pull, the sort of thing common in the offices of the 1930s. It had reached the end of its natural life: fibers of its thick paper walls had begun to fray and disintegrate. Inside, there were hundreds of letters held together by rubber bands that had long since lost their snap; they dissolved as they stretched.

They were not from patients.

They were penned before, during, and just after World War II by friends, a half brother (my great-grandfather had married twice and had a son far older than my grandfather and his sister), nieces, uncles, cousins, aunts—many, though not all, strangers to me. The letters,

dated from 1938 to 1941, were nearly all from Jews desperate to save themselves, to save one another. The letters dated after 1945 were efforts to reach out to those who had survived, tentative attempts to reconstitute a world after the Nazis were vanquished. Were they purposely placed in this mislabeled box? There

were

a few patients’ letters scattered among these papers—was it an innocent mistake? Or had he consciously kept them away from my grandmother’s eyes? It was shocking, a collection she had somehow overlooked, never opened; it must have sat in his office on North Street, in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, until the day he could no longer practice. And at that point he brought them home, tucked them away somewhere, and somehow they had missed the purge.