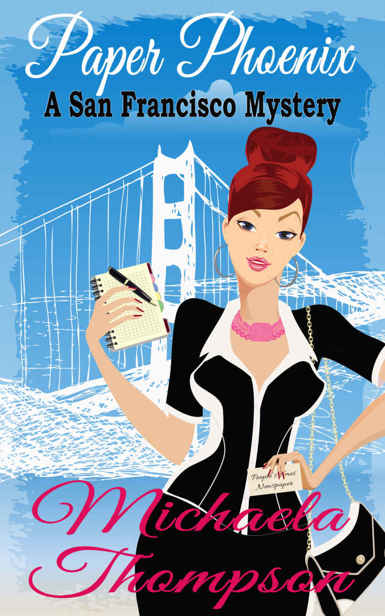

Paper Phoenix: A Mystery of San Francisco in the '70s (A Classic Cozy--with Romance!)

Read Paper Phoenix: A Mystery of San Francisco in the '70s (A Classic Cozy--with Romance!) Online

Authors: Michaela Thompson

Tags: #Mystery, #San Francisco mystery, #female sleuth, #women sleuths, #mystery series, #cozy mysteries, #historical mysteries, #murder mystery, #women’s mystery

Praise for

Paper Phoenix

:

“Wickedly delicious… What makes (Thompson's) book so particularly wonderful is the way it accomplishes the detective novel’s covert mission of urban analysis and social criticism.”

—

San Francisco Examiner

“(She) knows how to create that sense of place which is so important to any novel, but particularly to crime fiction; her characters are believable men and women in a real world…”

—P.D. James

Paper Phoenix

A Mystery of San Francisco in the ’70’s

By Michaela Thompson

booksBnimble Publishing

New Orleans, La.

Paper Phoenix

Copyright 1986 by Mickey Friedman

Cover by Andy Brown

ISBN: 978162517467

All rights are reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

First booksBnimble Publishing electronic publication: June 2013

eBook editions by eBooks by Barb for

booknook.biz

Other Books by Michaela Thompson

A Respectful Request

About the Author

Until Richard left me, I had never thought much about murder. After he left me, I thought about it a great deal. Being abandoned by your husband when you’ve just turned forty-four is enough to make any woman consider violence, and being abandoned for a law student almost exactly twenty years your junior is a situation begging for mayhem.

But violence in the abstract, such as a satisfying fantasy of beating Richard bloody, is a long way from the real thing. Larry Hawkins’s death and its aftermath taught me that, and a good deal more besides, at a time when I imagined I had very little left to learn.

The popular wisdom of the moment said that I was OK and you were OK. I could go only halfway with that. I

was

OK, or I had done my best to be. I had been faithful, supportive, loyal, an ornament to Richard’s career. I had gotten myself on committees of various cultural and philanthropic organizations and willed myself to care about their projects. I had sat through political dinners, my eyes watering with cigar smoke and suppressed yawns, when I would’ve preferred being at home with a good book. I had been pretty close to OK.

Nothing could convince me, on the other hand, that you were OK, if “you” meant Richard. Because to kick a perfectly OK wife in her stylish-but-not-flashy posterior is not OK and never will be, no matter what writers sympathetic to the problems of the male menopause say.

I thought about murder. When Richard closed the door behind him, my career as Mrs. Richard Longstreet, San Francisco Big Shot, was officially over. I was left with a renovated and rapidly appreciating pre-Earthquake cottage on Lake Street with a dining table at which the mayor would never again have dinner. The curtain had descended, and I was left in the dark backstage with the sudden suspicion that my big scenes had already been played.

A difficult situation was made more difficult by the fact that 1975, the year of Richard’s defection, was also the year that San Francisco— or, perhaps more accurately, the San Francisco press— discovered older women. In previous times, we females had marked the passing years in relative tranquility. Now, we were in ferment. At the age of forty-four, fifty-four, sixty-four, we were retreading ourselves for the job market, taking assertiveness training, petitioning our congressmen. We were banding together and starting cute new restaurants. We were learning carpentry and setting up communes on rolling acreage north of the city, where we birthed calves, walked around in mud-splattered hip boots, and lived in raw redwood cabins with no indoor plumbing. We were on the move.

I wasn’t going anywhere. Sitting in my glass-enclosed sun porch overlooking Mountain Lake Park, I would drop the paper beside my chair and watch the winter rain batter the weaving branches of the almond tree. When I got tired of doing that I would take a pill and lie down.

Since I wasn’t ready for calf-birthing, I had, as I saw it at the time, three possibilities: dye my hair, take a cruise, or commit suicide.

I decided against dying my hair. Even with a little gray here and there the chestnut was holding its own. After briefer consideration I also dismissed cosmetic nips and tucks on the eyelids and jawline. “You have good bones, Maggie,” my mother used to say, comforting me for being too thin. By this time I was glad. The less flesh, the fewer possibilities for sagging. My chin was a bit sharper than when I was twenty, and my eyes (the color of apple-green jade, Richard had rhapsodized in happier days) had seen a lot more, but I’d continue without chemical or surgical intervention. If Richard had chosen to see me, his domestic reflection, as on the verge of decay, that was his problem.

No cruise, either. I wasn’t ready to fend off the attentions of vacationing liquor salesmen whose wives were confined to the cabin with a touch of

mal de mer

and playing shuffleboard with other fun-loving divorcees didn’t appeal to me either. What I dreaded most was the thought that I’d probably fling myself at some greasy-haired ship’s vocalist wearing a diamond pinky ring and, worst of all, be rejected by him.

Suicide was my last option. I finally nixed it because I was too damn mad at Richard to give him the satisfaction. He would have played the scene well. His gray hair and elongated face gave him an attenuated, spiritual look that his black suit set off wonderfully. He would have stood, to all appearances guilt-ridden and grief-stricken, at my bier, and every woman at the service would have thought he looked worth committing suicide over. And underneath it all, he would have felt nothing.

***

If Larry Hawkins hadn’t died, I might never have taken off my salmon-colored peignoir again. Looking back, it seems that I wore it all day, every day, for months. That can’t be true, because I am fairly meticulous, and must have laundered it occasionally. I don’t remember. In fact, I remember very little of that time. I moved through the days like a salmon-colored blur, soft around the edges and the center completely dissolved, like a piece of chocolate candy that’s been left in the sun. Or like my marriage. My marriage had dissolved, too. That’s why they call it “dissolution of marriage,” I reasoned in my befuddled way. My brain didn’t work so well in those days, because I was taking a great many pills.

There was a pill in the morning, to calm my system down from the shock of getting out of bed. Then one at noon, to prepare me for my afternoon nap. At bedtime there had to be another to assure me of a good night’s sleep. Those were the regulars. If I started feeling jumpy in between, or burned the toast, or got a phone call from my lawyer, it was reason enough to take another. I was turning into a dissolving, salmon-colored junkie.

This situation continued from before Christmas to early March. How long it might have gone on I don’t know. I suppose I could still be stumbling around the house, subsisting on canned soup and staring moodily at whatever happened to be on television, if I hadn’t been awakened one afternoon by the sound of the newspaper slapping against the front steps.

It was four o’clock, and I had been sleeping since one. From what I had seen out the windows, it had been a glorious early-spring day— the sky a profound California blue, the park meadow the daisy-spangled bright green that comes after periodic hard drenching. Through the branches of the almond tree, now furred with delicate white blossoms, I had seen some neighborhood athletes braving the muddy parcourse. Then I had gone to sleep. When the thump of the paper penetrated my stupor I opened my eyes and watched the patterns the lowering sun was making on the bedspread of the king-sized bed in which I lay, still habituated, on my accustomed half.

The

Herald

. For once the delivery boy hit the steps, instead of the Japanese magnolia tree next to them, or the slick-leaved boxwood bushes at the bottom. What time was it? I was distinctly put out. The newsboy’s accuracy had robbed me of another half hour to forty-five minutes of sleep, which would have meant my waking just in time to start thinking about which Campbell’s production to have for dinner. Now, it was too early.

When each minute of consciousness is a burden, an extra forty-five of them constitutes an almost insurmountable tragedy. What in hell would I do until dinnertime? I concentrated, watching the motes of dust spinning slowly in the ray of sunlight that had slipped past the curtains. I would read the paper. It was poetic justice. The paper woke me, so instead of taking my usual cursory glance at the headlines, I would read every story in the paper, and then I could eat, watch television, and take another pill. Full of purpose, I climbed out of bed.

I almost gave up. More Watergate fallout. Another stabbing at San Quentin. A group of “displaced homemakers” was petitioning Congress for reform of the marriage laws. Fifteen minutes had passed. Basic Development Corporation, low bidder on the project, had submitted final plans for the proposed Golden State Center to Richard Longstreet, San Francisco redevelopment director. That was too much. It was hard enough putting Richard out of my mind without reading about him and his idiotic Redevelopment Agency in the papers. Grimly, I leafed through to the obituary page, possibly hoping to see his name.

The name I saw wasn’t Richard Longstreet, but Larry Hawkins.

It was a short, uninformative article headed

LOCAL EDITOR DIES IN FALL

. I read it three times without stopping:

***

Larry Hawkins, 35, editor-publisher of the

People’s Times,

a weekly newspaper devoted to local politics, was found dead this morning in an alley outside the

Times

offices at 1140 Cleveland Street, a police spokesman said. Hawkins, an apparent suicide, had fallen from his office window on the building’s seventh floor. A note was found, the spokesman said.

Hawkins, self-styled “gadfly” of the City’s political establishment, was a well-known local figure. The

People’s Times

began publication three years ago. Hawkins is survived by his wife, Susanna, and two sons.

I put the paper down. So Larry Hawkins had committed suicide. I must have seen him a hundred times, maybe more— a slender man about five feet four, with a Byronic profile and a tumbling, unkempt headful of black curls, a rather attractive air of grubbiness about him. Although he was known to feel that anyone connected with City Hall was a natural adversary, there were people who considered it chic to flaunt their liberal tendencies and hound’s-tooth cleanliness by inviting him to their parties. Perhaps they wanted to show they weren’t afraid to let a righteous radical journalist loose in their china closets, no matter how out of place he might look and be.

Why he attended these gatherings I don’t know, unless he was in search of stories. I doubt that was the only reason. I think he got some sort of thrill from swaggering into an impeccably dressed group wearing his dirty beige corduroy jacket, his patched jeans, and his cracked boots. His moral superiority was evident always. He showed it in his contempt for all of us, the establishment he despised and excoriated week after week in the

Times

. After a perfunctory handshake for his hostess, he would usually station himself as close to the food and drink as possible, watching everyone with quick, dark eyes. And the next week, likely as not, one of his fellow guests would turn up in the pages of the

Times

as having given the City rest room contract to a toilet paper firm owned by his brother-in-law.

I wasn’t thinking about Larry now, but Richard. When I closed my eyes, I could see his long fingers curving around the telephone receiver, see his straight, navy blue, impeccably tailored back. I could hear his voice saying, impatiently, “Sure, I agree Larry Hawkins is a pain in the ass…” I had stood in the doorway of the study, wearing the same salmon-colored peignoir I was wearing now. It was the end of October, and Richard was going to leave me.