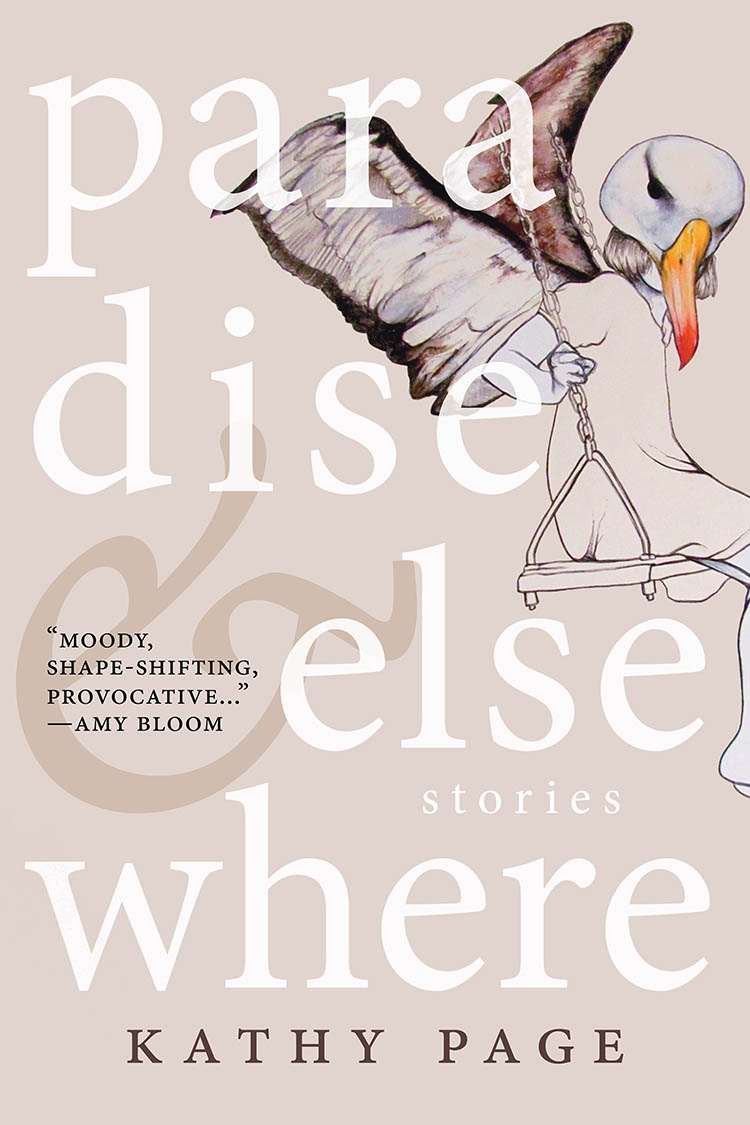

Paradise and Elsewhere

Read Paradise and Elsewhere Online

Authors: Kathy Page

Â

Â

Â

Paradise

&

Elsewhere

Â

Stories

Â

Kathy Page

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

a

JOHN METCALF

book

Â

BIBLIOASIS

WINDSOR, ONTARIO

Copyright © Kathy Page, 2014

Â

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Â

FIRST EDITION

Â

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Â

Page, Kathy, 1958-, author

Paradise and elsewhere / written by Kathy Page.

Â

Short stories.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-927428-59-7 (pbk.).--ISBN 978-1-927428-60-3 (epub)

Â

I. Title.

Â

Â

PR6066.A325P37 2014 823'.914 C2013-907292-6

C2013-907293-4

Â

Edited by John Metcalf

Copy-edited by Allana Amlin

Typeset by Chris Andrechek

Cover design by Kate Hargreaves

Cover illustration by Stephanie Grogan

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Biblioasis acknowledges the ongoing financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Council for the Arts, Canadian Heritage, the Canada Book Fund, and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Arts Council.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

G'Ming

Â

Â

Â

Â

T

he village looks

closer to the road than it is and I see them coming from a long way off, their clothes bright white against the mud and the scrub of the plain. Most often it is a man and a woman together like this; the man has a camera, and both of them wear money belts around their waists. When they reach the path I slip down from the wall. I watch them coming around the twist in the path; they see me, and I smile.

The woman wears big dark glasses: some years the glasses are big, some years small. She carries a plastic bottle of water. You can see the shape of her body beneath her clothes, the damp patches under her arms. The man is thin. He is beginning to go bald, and although he moves loosely he stoops from being tall. He doesn't wear sunglasses and there are lines on his face, whiter than the rest. He smiles right back when he sees me. Normally it is the woman, but today, he is the one, and so we begin:

“I offer you a good afternoon.”

“To you also,” the man replies: he has some of our language, then, but it will not be so much as I have of his. I offer my hand to shake, first to him then to her. The woman makes a noise in her throat. She flaps her other hand around to chase away the small brown flies that come at this time of year; it only makes them worse, but foreigners never see this.

“My name is Aeiu,” I tell them. Theirs are Nick and Liz. And now we have made an exchange, which prepares the ground.

“It is beautiful here,” she says. Truly, I don't know if it is or it isn't beautiful. There is earth, sun, water, trees. There could be hundreds of places like this.

“Very beautiful,” I tell them, as they nod and agree. “And your wife,” I say to the man, “she is like a gazelle.” And then we walk together, on towards the village.

I am sixteen but I look less so I tell them twelve. I have two younger brothers and one older and one sister, not married. My father's brother is a holy man who does not have to workâpeople bring him gifts of food and drinkâbut the rest of us start with the sunrise. I tell them this and they nod hard again when they understand and say “Good.” It is not particularly good, it is how things are, here in G'ming, where I live. Though I do not say that.

The mud walls rise higher either side of the track and as we come into the village, the shade grows deeper. Branches hang over the walls, heavy with fruit. The man and the woman look around with big eyes. But they don't look behind and neither do I. I know without looking that by now the others, the little ones, are following us.

“These are pomegranates.” I pick one for the woman. “To quench your thirst. Perhaps you would like to buy a basketful? Or maybe some of our pottery, all very cheap.”

“We are just walking, thank you,” she says. “We are not buying.” We come to the centre of the village, where all the paths meet in a star, which is the marketplace every week, busy, busy, busy. But now it is quiet. The sun is almost overhead, no shade, no sounds. They hesitate, aware of the stillness, and then the boys who have been following break suddenly upon us, laughing and shouting.

It would make a good photograph: the two tall ones, the twenty or so smaller ones, somewhere between their knees and their hips in height, jostling, reaching up. Hands to shake. Lots of shaking. Good afternoon, the man and the woman say back, making our sounds strange. And as for myself, a figure between the two heights, I stand for a moment a little apart. The man has his hand in the small of the woman's back. His camera is Minolta.

Â

A

re you a growing

to be a good man, Aeiu, or a bad man?

Since my tenth birthday, my father insists that every year I take an offering to his brother, the holy man. If I am honest, I do not like him. He smells like rotting fruit. He tells me that I should think on this question of goodness and badness as many times a day as I can. It is the way to true riches, he says. He sits by the river all day. It seems to me that he has no obligations.

That is not so, Aeiu, he says, his eyes fixed on the distance, even when he looks right into my eyes. As if the distance were inside my head too.

I know only that I am good at doing certain things. This.

The kids hold their hands out. “Aeiki!” they say, first one, then the rest.

“No aeiki,” the man says, loudly shaking his head, but smiling still.

“Aeiki, one aeiki. One dollar!” They cluster around so it is hard to walk and the woman looks back along the track they came down, as if she wants to return. Instead, they veer right, away from the village and down towards the river. We all follow.

“No,” the man says. He puts his hand in his pockets and pulls the linings out. Uuio comes forward. He has greasy white cream on the patch of skin on his forehead, and the dust has stuck to it. He taps the man's pouch, and we can all hear the ringing of coins inside.

“Aeiki,” he says. But the man, still smiling, shakes his head. And because so far I have asked for nothing, he looks to me for help.

“There are twenty aeiki to one dollar,” I say, and shrug, as if to say it is nothing to do with me.

“But why?” the man says, turning back to the kids. “Why aeiki?” So very stupid.

“Aeiki, dollar, aeiki!” they call back.

Â

T

he trees stop suddenly

and the path finishes at the river, where the women are washing clothes and all the coloured things are spread out to dry on the bushes. They stop work and stare back and some of them cover their faces. The kids are asking for pens now, or sweets; they try different languages:

“Stylo, bonbons!” They mime writing, eating, hunger.

“We have nothing,” the woman says. A lie. Does she think we have no eyes? She has folded her arms across her chest. They want to be friendly without giving. But this is not possible: why do they think they can pretend a walk here is the same as a walk in their own village? Do they truly expect to come here for nothing? They are seeing my home: they have already had what they wanted. I will never be able to see the place they come from, to walk around it, looking. I do not have a picture of it in my mind, unless it is New York, Hong Kong, or London.

“Aeiki, pen, dollar, Coca-Cola, aeiki, stylo.”

“It is beautiful here,” I remind them. “Maybe you can take a photograph.”

They look at each other quickly. “No, no, no,” the man says. “No photographs.” But Eeiu and Aui come forward to put their arms around the woman, one each side, and rest their heads on her waist.

“Photo!” they cry.

“No photo.”

“Photo!”

“Their poor teeth,” the woman says.

“No photograph. Camera finished!” the man says, making a gesture like scissors with his hands.

Eeiu and Aui hold their pose.

“Ten Aeiki,” they say.

“No photograph. No aeiki, no dollar,” the man tells them. The woman breaks free and Eaio taps her on the arm: he's the oldest after me, but very thin, and he has a small face that looks as if it has suffered much. He points at her bottle of water, then at his mouth. We have both a river and a well, but this they can't refuse. So he drinks, passes the bottle on. An important step. For a short time, everyone is quiet.

“Aeiki, dollar,” the boys begin again as we walk back from the river. Then the man takes the empty bottle back and holds it up.

“Soccer? Football?” he says, looking around, smiling very hard. He kicks the bottle. It doesn't go far. He runs after it and looks back at us, kicks it towards Uuio. Uuio passes to Eaio. Eaio to Oii, who heads it back to Uuio⦠Others rush forward, passing the bottle to and fro until it is crushed and the man, breathing hard, smiles at the woman, a big smile.

“They're just kids,” he says.

We are beyond the marketplace now, following the path. Smaller tracks leave off to either side, like the veins of a leaf. The old men sleep on a bank in the shade of the orange trees. Just like my uncle, the one who is a holy man, old men do not have to work, I tell the tourists.

“Aeiki, dollar, aeiki,” someone begins. The man turns and puts his tongue out. He puts his finger in his mouth and pulls it, making a noise like the cork from a bottle. Some of the younger ones do it back. But it doesn't last.

“Come to my house.” Uuio mimes setting a cloth on the floor then pouring and drinking tea.

“Hospitality,” I explain. “You should accept.” And now yet others join us and some of the kids try to chase the newcomers away. The woman notices this.

“It is very kind. We want to be friends, but we do not have time to visit,” she says.

“No time? On your holiday?”

“We must leave now.” She looks ahead. There are many paths.

“Up to you,” I say. I am good at this. I need not hurry, because it will work out for me, either way. If they give to the others, they will also give to me. If they do not give to the others, still, in the end, they will give to me.

“You are in a car?” I ask. The man mimes walking, two fingers on the back of his hand.

“This way for the hotel!” says Uuio. It's the way to his house, of course.

“I think it's this way,” the man says to the woman, pointing. They hesitate.

“This way,” Uuio insists, which almost always works, but these two walk forward, fast, the way they have chosen. The path turns a blind corner and leads to a bank of sandy scrub and tamarisk trees.

“Come back! This way!” Uuio insists. Again they hesitate, but finally they stride on up the bank, fast as they can, slipping in the sand. Some of the smaller ones drift away now. The rest of us follow. From the top of the bank, across the plain are the two piles of stones that mark the edge of the village's land, and then the road and then the hotel. It is small in the distance but by luck they have chosen the shortest way. We follow quietly for a while as they descend the bank, talking to each other in low voices. Once or twice they check to see if we are still there.

At the stones, we are close behind them again. They turn around together.

“Goodbye,” they say, as we gather around. The man points at himself and then the hotel, at us and then the village.

“Goodbye,” he repeats. Euu, the smallest of those remaining, reaches up to the woman, his lips puckered for a kiss. She bends down and kisses the air to the side of his cheek: she does not want to do this, I can tell. Others follow and she kisses the air besides all of them. When that is done, the man and the woman wave and say goodbye again. No one moves. We stay surrounding them. There is a moment of silence, then Euu says:

“Just one aeiki, just for me.”

“But no,” the man says softly, “That's itâdon't you see? Not fair.” He points at all of us. He looks at me.

“Not

fair,

” he says. There is a new expression in his eyes, a kind of burning I can't name.

“Fair?” I say.

“Aeikiâaeikiâaeiki” he says pointing at us all.

“There are twenty aeiki to one dollar,” I repeat. Sometimes, when they have been here for a while, they forget this. “It is not much.”

“Not much, butâ” he points at us again, and then into the distance, towards the city, continuing “aeiki, aeiki, aeiki.”

Uuio pushes through the others.

“One dollar to me. Little bit each one,” he says, smiling hard as he mimes the cutting up of the coin, as if it were a pie.

“

Share

?” the man says, looking hopefully into Uuio's eyes. Uuio nods. The woman says something very fast, her voice sharp. But then she smiles at the man very softly as if he were a child and he opens his money belt. Of course he does not want us to see how much money he has in there, so his fingers are awkward. He pulls out two coins. One he puts in Uuio's hands. The other drops to the ground: everyone fights. Eeai wins it and runs back to the village. Uuio follows. Dust flies up after them.

Aeiki, aeiki, the unlucky ones call. They grasp at the man's legs, reach for the money belt.

“No! That's it! Go away!” he says, pushing the hands away. His voice has changed. He's angry, or something like it. The woman puts her arm through his. They take a few steps. We follow.

“Please!” the woman says over her shoulder. The man does not turn around at all. I go around to the front of them, hold out my hand, to the woman this time, palm up.

“Ten aeiki,” I say. “Give me ten aeiki. Then I will make them go.”

“What?” she says.

“Ten and I will make them go. And ten for me, for me to go,” I say, “twenty in all.” I hope they understand how foolish they have been. They could have paid and seen properly, seen inside our houses, taken their pictures, but now they must pay anyway, without doing these things.

“For Chrissake!” The man spins around, opening the pouch as he does. They never have change: it's a fifty aeiki note.

I take it and bow my head as I thank him. I will ride the bus to the town and change the note for smaller currency there. I will keep ten, maybe fifteen for myself and give the rest to my father. I've never told him I do this, but perhaps he knows and says nothing. After all, it was he who stopped me going to school, and I pay my way now. And I honour my bargain with the tourists also; I tell the boys to go and they do. Later I will give them something.

I take one last look at the man, Nick. He stands there with his money belt still open and looks back at me. There is something not right. His face is loose and the eyes in it are shining: the skin under them is wet with tears. He takes a deep breath, turns away. The woman, Liz, reaches up his back, rubs the space between the shoulders and they walk away across the plain. They stay together like that and they do not look back.