Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light (18 page)

Read Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light Online

Authors: David Downie

Tags: #Travel, #Europe, #France, #Essays & Travelogues

Redone recently under the direction of an art historian and advisor to Karl Lagerfeld, the furniture embraces the styles of Louis XVI, the Directoire and the Empire; in other words, it is gilt and gaudy, presumably the way Chanel liked it. “Sixty craftsmen worked around the clock for two months,” says the Ritz, “to complete this work of art, perfect in every detail.” The taps in the stone-clad bathroom are gold plated. There are even Coromandel screens like the ones in Coco’s Rue Cambon sanctuary. Views from the windows take in the eighteenth-century architectural gems lining Place Vendôme and, of course, the celebrated column with its imitation Imperial Roman low-relief sculptures. Like so many symbols of oppression, it was toppled more than once by riffraff and re-erected by the powers that be.

The one time I talked my way into the suite I couldn’t help staring out of the window, contemplating the column—and the fact that in 1934, when she first checked into the Ritz, Coco’s enterprises boomed despite the worldwide Depression and the violent workers’ riots and strikes in which her own employees took part. Business roared for her throughout the grim thirties, in fact.

But money wasn’t everything to Chanel. The premature death of her beloved Iribe in 1935 seemed to prove yet again that Coco was as unlucky in love as she had been successful in commerce. A few years later, even that changed: the distant thunder of the Second World War was beginning to shake Coco’s comfortable universe. In the summer of 1939 she fled Paris. During the Occupation, however, she quietly moved back into the Ritz. And the darkest period of her life began, a decade in which her name was attached to that of the shadowy “von D.,” a German intelligence officer. It’s this period that makes Chanel’s business heirs cringe, and is rarely, if ever, mentioned by anyone remotely associated with the Chanel fashion or perfume houses.

How did Coco Chanel escape the punishment meted out after the Occupation to the women who fraternized with the Nazis? As André Malraux, the celebrated essayist, critic, and first-ever French minister of culture, said, “Chanel, General de Gaulle, and Picasso are the three most important figures of our time.” She had friends in high places in France and, as the baubles on her coffee table in Rue Cambon attest, elsewhere among the war’s victors.

Chanel’s self-imposed exile to Switzerland after the war lasted until 1954, when she made a comeback. She was seventy years old and had not shown a collection since 1939. Christian Dior was all the rage. Undaunted, Coco revived her Rue Cambon shop and set to work. The show, initially panned by the reigning fashion moguls and called a “fiasco” by London’s then-influential

Daily Mail

, was hailed in America. The fame of her youth was revived.

Life

magazine credited her with revolutionizing the industry yet again. Asked who she dressed, Coco snapped, “Ask me who don’t I dress!” Over the next seventeen years, until her last snip of the scissors in 1971, she lived between her suite at the Ritz and her Rue Cambon apartment and shop. “I was a rebellious child, a rebellious lover, a rebellious

couturière

—a real devil,” she once confessed. That’s not a bad epitaph for the twentieth century’s greatest mind in fashion, a true Parisienne of the Golden Triangle.

Les Bouquinistes

They buried him, but all through the night of mourning, in the lighted windows, his books arranged three by three kept watch like angels with outspread wings and seemed, for him who was no more, the symbol of his resurrection

.

—M

ARCEL

P

ROUST

,

La Prisonnière

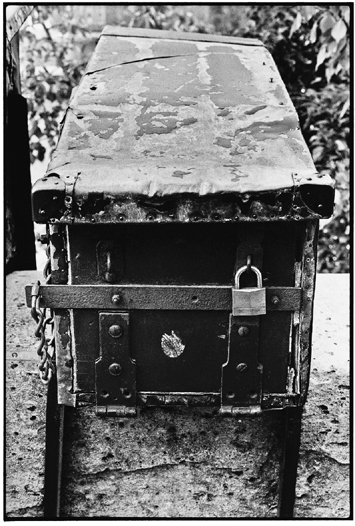

offins. Dilapidated dolls’ houses. Treasure chests encrusted with padlocks and bars. The battered green book boxes of the

offins. Dilapidated dolls’ houses. Treasure chests encrusted with padlocks and bars. The battered green book boxes of the

bouquinistes

, Paris’s quayside booksellers, slump evocatively along the Seine, anachronistic curiosities clinging to riverside parapets as they have for the past hundred-odd years.

A higgledy-piggledy wagon train several miles long loaded with something like five hundred thousand secondhand volumes, the boxes also overflow with posters, engravings, knickknacks, paintings, soft porn, leather-bound tomes, dusty paperbacks, statuettes, coins, coasters, and refrigerator magnets—the sublime, offensive, and ridiculous displayed side by side.

A city official once confirmed to me that there are about one thousand book boxes all told, all of them painted the same regulation

vert wagon

—the dark green of old train cars, old buses, old benches, and old railings left over from the Second Empire or the Third Republic. Despite the

règlement

, each box is a subtly different shade and shape, frosted here by lichen, blackened there by smog, rotted by rain and damp, scarred by reckless drivers and the inexorable passing of time, then patched and trussed and slathered with another layer of green paint. In the dark, especially on a wet moonless night, the boxes glistening under nineteenth-century street lamps take on a sinister, sepulchral cast—the objective correlatives of a dead Paris.

Look again on a sunny morning, though, when the booksellers who preside over the boxes make their way down the stone-paved sidewalks to unlock and prop open their treasure chests following a careful ritual, and the metaphors change. The battered

boîtes

morph into wood-and-tin grasshoppers lifting their legs, or gull-winged vessels carrying precious bundles from the reassuring past toward an uncertain future.

Squint, or use a telephoto lens to eliminate the traffic, and you can almost see novelist Anatole France—the most famous patron of late-nineteenth-century

bouquinistes

—picking through the swirling crowds, lifting a heavy volume then dickering over the price. It was in France’s heyday in fact, in 1891, that the itinerant booksellers of Paris’s quaysides were finally given the right to affix their boxes to the parapets, after about four hundred years of cat-and-mouse with municipal authorities. That game is now left to the unregistered, largely immigrant groups of bangle-hawkers who pack up and run at the approach of a gendarme.

I’m not sure why but I’ve always been drawn to the

bouquinistes

. To say I’ve befriended several would be an exaggeration, but as a regular customer I do know them and their wares. Many are great talkers, and a few know a good deal about the history of their trade. Apparently they take their name from the German

buchen

(books) or the Old Dutch

boeckin

—“little books.” In French, therefore, a

bouquiniste

is a seller of

bouquins

. A

bouquineur

is a book lover, collector, or reader like me (and most of us have no room for

bouquins

in our tiny apartments, which is why we do book swaps, to keep down the height of the stacks). It’s only logical, then, that the verb

bouquiner

means both “to troll the quays searching for books” and, more commonly, “to read up” or “study hard” by poring over textbooks.

Funnily no one I’ve talked to seems to know when these expressions were coined, though city records show that Paris’s first printing press was installed in 1470 at the Sorbonne—fourteen years after Gutenberg printed the first

buch

in Mainz.

Bouquins

began to circulate immediately thereafter among the scholars and priests headquartered in the Left Bank’s university neighborhoods. By 1500, the city’s earliest permanent bookstores had begun to spring up there, and by around 1530, groups of itinerant booksellers were walking the streets of the Cité and the bridges connecting the island to either side of the Seine.

As is their wont, from the start, the powers that be regarded with a baleful eye these motley

bouquinistes—

suspicious, perhaps subversive indigents selling their wares off ground cloths or from trays hanging from straps around their shoulders. A 1577 police document compares them to “fences and thieves” in part because during the wars of religion, many

bouquinistes

sold Protestant pamphlets or “subversive tracts” printed abroad. Routinely the king’s men would round up and jail the

bouquinistes—

or do worse.

In 1606, Paris police authorities decided to regulate the trade, limiting business activity to daylight hours and restricting the sphere of movement to the riverbanks “in the vicinity of the Pont-Neuf.” These early booksellers were allowed to display their goods on the parapets and roadsides (there were no sidewalks back then in Paris, except on the Pont-Neuf itself). The number of vendors skyrocketed during the French Revolution, when the collections of countless noble families were confiscated and auctioned, or stolen by angry mobs, as patrician heads tumbled into bloody baskets in what’s now Place de la Concorde. Eventually many of the aristocracy’s books made their way into the hands of the

bouquinistes

, and in the course of the past two hundred years these valuable volumes have been sold and resold many times on the quays.

Order and symmetry have long been national obsessions among France’s administrators, and they are regularly subverted by institutionalized revolution. The dimensions and distribution of the

bouquinistes

’s boxes go back to the Third Republic, when enlightened municipal officials decided to give the families of wounded veterans and war widows the right to leave their

boîtes

clamped to the riverside walls. A few minor reforms were made to the

règlement

in the 1940s (establishing the total length—exactly eight meters—of parapet allotted per

bouquiniste

) and in the 1950s (the uniform application of

vert wagon

as a color). In 1993, the City of Paris began requiring

bouquinistes

to open at least four days a week, limit consecutive days off to six weeks per year, buy a business license, and pay social security and income taxes (usually about thirty percent of declared gross revenues). Licenses now go to individuals from all walks of life, not just to needy families.

Predictably the

règlement

isn’t always respected, but it has kept the worst abusers at bay. Of the four regulation green boxes each bookseller may exploit, at least three must now contain only books. In the fourth, the

bouquiniste

can display “souvenirs related to Paris,” which explains the proliferation of miniature Eiffel Towers, Notre-Dame gargoyle paperweights, postcards, and faux-Hermès scarves showing the Arc de Triomphe or other monuments.

One day I buttonholed a youngish woman named Laurence Alsina, who turned out to be a fourth-generation

bouquiniste

. Her boxes face number sixty-five on the Left Bank’s Quai de la Tournelle kitty-corner to Rue de Bièvre. “I was born on this sidewalk,” she told me with understandable pride. “But we can no longer survive selling only books.”

With Notre-Dame as a backdrop, Laurence has an ideal location, yet there are days, she noted, when she doesn’t sell a single

bouquin

. Carefully wrapped in cellophane, her classics of literature, history, and travel are flanked by the usual selection of postcards and posters—the moneymakers. “In summer, tourists want secondhand classics like

Madame Bovary

,” she sighed. “Off season, Parisian collectors, quayside regulars, and journalists buy out-of-print or rare books, but people just don’t read as much anymore …”

The Internet, CDs and DVDs, videos and computer games have squeezed the

bouquinistes

’s market share. Still, Laurence’s family runs three sets of boxes and shows no signs of giving up. Her father, Marcel Baudon, hails from the Quai de Montebello facing Shakespeare and Company. Her sister, Véronique le Goff, is on the Quai Saint-Michel near the RER station entrance, facing number three. Like most

bouquinistes

, the whole family is driven by an obsessive passion for books—quayside lifers call it

la maladie des livres

. It’s also what keeps them going despite meager takings: city officials estimate average monthly earnings per licensee at one thousand to two thousand dollars.