Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light (31 page)

Read Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light Online

Authors: David Downie

Tags: #Travel, #Europe, #France, #Essays & Travelogues

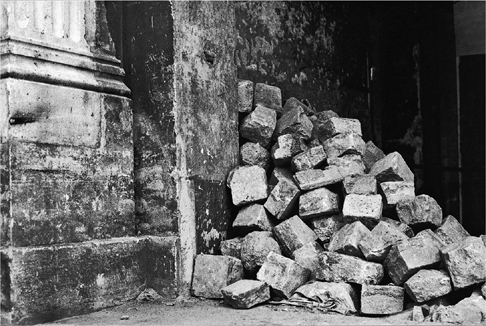

In some ways it was an ideal city, a military man’s Utopia conceived by Emperor Napoléon III and engineered by his prefect Baron Haussmann. It was anything but ideal, though, for nostalgics or romantics. In

Les Fleurs du Mal

and other works, Charles Baudelaire scented death and urban anguish in Haussmannization—the radical modernization that resulted in the demolition of the medieval city. “Old Paris is gone,” Baudelaire wrote in

The Swan

. “No human heart changes half as fast as a city’s face.”

Haussmann’s was an ideal cosmopolis for those who believed in order, uniformity, and the hygienic properties of open air and sunlight. At Napoléon III’s behest, the prefect brought down some twenty-five thousand buildings in fewer than twenty years. Broad cannon-shot boulevards and regular street alignments with uniform façades rose where a tangle of dark alleys had once been.

With few exceptions the Impressionists and early photographers who documented this remade world were fascinated by its novel cityscapes and seemingly endless perspectives. They sought above all to capture the effects of a new kind of light that was at once physical and spiritual. It was the light that sifted through the trees planted on the new boulevards. Or the light cast by the hundreds of

réverbère

gas lamps installed in the 1860s on the sidewalks of those boulevards. Light streamed into the tall French windows of modern buildings. Lights burned around the clock in the new cafés, theaters, and train stations that sprang up around town. By association,

la lumière

was also the enlightened attitude of the inhabitants of this marvelous new world.

The late nineteenth century’s Universal Expositions, in particular that of 1889, which marked the centennial of the Revolution and the building of the Eiffel Tower, seemed at the time to herald a new age of technical progress and scientific reason in parallel to the artistic flowering of the Belle Époque. We may marvel today at their ingenuousness, but most of the spectators of all classes and walks of life who crowded around to watch the Tour Eiffel’s inauguration in 1889 were astonished, transfixed, and delighted. The world’s tallest structure at the time, it was lit by ten thousand gas lamps. Fireworks and blazing illuminations drew the spectator’s eye to various levels. A pair of powerful electric searchlights—among the earliest of their kind—raked the city’s monuments from the summit at a height of 986 feet. Some say it was this signal event that engendered the name Ville Lumière. If so, no one bothered to write it down.

Admittedly not everyone was bowled over by the tower, its lighting display, or what it stood for. Caricatures and political cartoons of the period show strollers shading their eyes at night, blinded by Paris’s newfound modernity. One cartoon’s caption noted that from then on, people would need to use seeing-eye dogs to go out for an evening stroll. By the 1890s, most of the city’s gas lamps had already been replaced by even brighter electric lighting (though the last gas

réverbère

in central Paris was removed only in 1952, and at the dawn of the twenty-first century one still existed just outside the city limits).

It’s no surprise then that at the Belle Epoque’s zenith, which coincided with the Universal Exposition of 1900 and its further technical wonders, a novelist named Camille Mauclair wrote a book titled

La Ville Lumière

—“The City of Light.” This is the earliest documented use of the term as applied to Paris. The book was published in 1904 and has been out of print for decades. No one seems to remember precisely what it was about. Georges Frechet,

conservateur

at the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris, has suggested that the novel probably drew inspiration for its title and content from both the 1900 Universal Exposition (one of the exhibits, La Fée Electricité, was a celebration of the miracle of electricity) and the intellectual ferment generated by the period’s artists, performers, and writers, Stéphane Mallarmé foremost among them.

But what of the actual lighting of Paris? Though it has been “modernized” repeatedly, Paris

intra-muros

—meaning the city within the Boulevard Périphérique beltway—retains many Second Empire features. Other than minor damage in 1870–71 caused by the Franco-Prussian War and Commune uprising, it was never bombed or burned. Real estate speculation has caused the greatest damage.

This apparent changelessness goes beyond the physical. Jean-Paul Sartre described Baudelaire as a man who “chose to advance backwards with his face turned toward the past.” In many ways the same can be said of Paris and the people who reside in it. Photographer Robert Doisneau once called Paris a “museum city,” though “amusement park” might have been more accurate, at least as regards the attitude of many visitors. The weight of history, institutions, and culture forces natives and other inhabitants to glance back while moving forward.

Sartre’s and Doisneau’s observations seem particularly apt when applied to the nuts and bolts of lighting the Ville Lumière and to the philosophy, if one can call it that, underlying the myriad of light-related technical and bureaucratic constraints at work. For a down-to-earth example, consider the many light fixtures on Paris streets that were installed before or during the Second Empire. Haussmann-style lamps are still manufactured today. There are also Art Nouveau fixtures and others added in the 1930s. Are they obsolete? Of course. But no one would dream of removing them. Why? Atmosphere. The atmosphere Paris’s old-fashioned lamps create is warm, welcoming, and infused with nostalgia. Nostalgia is both a state of mind and a cultural ID card. No other city goes to such lengths or spends as much money—about three hundred thousand dollars a day—to create a retro “light-identity,” an ambience that immediately declares, “You’re in Paris, the City of Light.” In many places you could be walking alongside Baudelaire or Brassaï or Sartre through a crepuscular time tunnel.

This is something most residents and visitors alike take for granted. But behind the scenes, a score of

éclairagistes

and

concepteurs-lumières

(lighting designers)—plus architects, engineers, and some four hundred technicians—are hard at work around the clock creating Paris’s evening magic.

Raise your eyes from just about anywhere in town and you’ll see how lighting designer Pierre Bideau has illuminated the Eiffel Tower with hundreds of small sodium lamps. The tower’s golden lacework glows from within, recalling the gas lighting of 1889. A twenty-first-century novelty, like clockwork it sparkles and bursts into a glittering dance every hour, as a searchlight rakes across town, another reminder of 1889.

Louis Clair’s delicate lighting of the Rotonde de la Villette underscores the curves and colonnades of architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s fanciful eighteenth-century canal-side customs house. Clair’s luminous transformation of the church of Saint-Eustache from inhospitable hulk into glowing beacon traces the flying buttresses and lets light leak outward through the stained-glass windows.

Roger Narboni and Italo Rota—two other bright stars in the French lighting firmament—have worked together or separately to capture with lights the physical and spiritual essence of Notre-Dame cathedral, the Louvre, a handful of bridges over the Seine, and famous avenues such as the Champs-Elysées. Architect Thierry Van de Wyngaert managed to transform the banal 1970s skyscraper at the notoriously unappealing Jussieu university campus into an intriguing, multicolored lighthouse. But there are dozens of other equally impressive nighttime scenes: Place Vendôme and its storied façades look to me like a stage set; the fountains of Place de la Concorde or Boulevard Richard-Lenoir splash both water and light.

What these projects share, their planners assure, is the goal of bringing forth the history and symbolism of each site. Flamboyant, experimental, or garish lighting displays that might seem marvelous elsewhere don’t work here on anything more than a temporary basis—and sometimes they provoke an immediate outcry. For instance, a few years ago Paris’s lighting engineers were playing around at Sacré-Coeur atop Montmartre and turned the basilica mauve, precipitating a kerfuffle with the priest in charge.

True, avant-garde French light-sculptors like Yann Kersalé do create works in Paris for special occasions (July fourteenth extravaganzas, bicentennials, and so forth). And many French lighting designers rightly consider themselves artists or

créateurs

. But for them to succeed, their talents must be solidly anchored to the city’s multilayered historical reality. To transpose Sartre’s celebrated description of Baudelaire—moving forward with his eyes on history—they must light the future by illuminating the past.

“If you don’t know exactly where you’re going, at least you can look back to the past and form some ideas,” said François Jousse, musing about the Parisian worldview in general and how it applies to lighting in particular. For decades Jousse was the chief engineer of Paris’s municipal lighting and street maintenance department, a title that described only a few of his functions. He’s the man who turned Montmartre purple for a fleeting instant. Not long before he retired, I met him at his office in a remarkably nondescript, ill-lit building near Paris’s beltway.

Modest yet contagiously jovial, the bushy-bearded Jousse is famous among French lighting professionals for his expertise on everything from the performance of electric bulbs to the philosophy of monument illumination or the history of lighting since Antiquity. Indeed if any one person is responsible for setting the city’s nocturnal mood, it’s Jousse.

Individual monuments, buildings, and bridges may take on a beautiful sculptural quality at night, Jousse readily admitted to me, but what most intrigues him is the night-lit city as a physical, metaphysical, and emotional whole—the grand display case of Paris and its lifestyles. “Drive into town at night from the suburbs and you feel the difference immediately,” he told me, his eyes twinkling. “From the linear, traffic-oriented lights leading you through and out of the suburbs you enter the floating blanket of Paris light—a destination, a place, the arrival point.” He stroked his beard and leaned back into his unfashionable office chair, readying himself for a stroll through centuries past.

As far back as the Middle Ages, lanterns or candles marked the city limits and the three most strategic points in town, Jousse explained. They were above all symbolic: the Louvre’s Royal Palace; the Tour de Nesle (a watchtower that once stood on the Seine); and the cemetery of the Saints Innocents, a favorite meeting place near Les Halles for thugs and lovers. Over the years, oil lamps were added around town. But it was the Sun King who lived up to his title and in 1669 inaugurated the first systematic public lighting scheme (he even had a commemorative lantern medal minted to celebrate it). By the 1780s, a pulley system had been devised to hang new, elegant lamps over the streets. And then came

le déluge

of 1789. “The refrain in the Revolutionaries’ song

Ah! ça ira

is all about hoisting aristocrats from the lampposts,” Jousse laughed. “And those new pulleys came in very handy.”

Paris’s nighttime identity as we know it today was largely defined with the advent of modern outdoor lighting in the mid-nineteenth century. Ever since, the city’s streetlamps have been erected at the same heights: six, nine, or twelve meters—about twenty, thirty, and forty feet (the Champs-Elysées’s fixtures, designed by Jean-Michel Wilmotte, are exceptions at 11.5 meters). Lampposts are staggered along the sidewalks on both sides of the street to create overlapping, gentle pools of light. The light laps at the buildings and hints at the roofline above the tops of the posts. The overall effect is to give Paris a human dimension, making it an inviting yet safe place to enjoy after the sun goes down.

“It’s the little things I like most,” said Jousse, echoing the sentiments of many Parisians. “For example, there’s a nineteenth-century wall fountain on Rue de Turenne not far from Place des Vosges that no one notices during the day. Even at night, drivers don’t see it. But when it’s lit with two small spots, it’s a wonderful discovery for strollers.”

Beyond the poetry and aesthetics, skillful lighting is one way to diminish vandalism in rough neighborhoods. Jousse is still proud that ever since his technicians illuminated a contemporary sculpture in the 18th arrondissement’s long-notorious Goutte d’Or quarter near Barbès, the locals have adopted it as their own. At Porte de Clignancourt, under the sinister spaghetti bowl of freeways where the city’s main flea market is held, Jousse and his lighting technicians lit a wall that was erected as a safety measure, to divide a wide sidewalk. Now, instead of being viewed as an ugly obstacle, the wall is a noctambulist’s landmark, a kind of luminous welcome mat on the city’s edge.

Half a dozen other cities probably have more and brighter lights than Paris. New York is a forest of flaming skyscrapers and throbbing, colored bands. Parts of Tokyo and Berlin look like immense, garish outdoor advertisements, the objective correlatives of our consumerist age. These forward-looking cities also sparkle as among the world’s great artistic, intellectual, and economic centers. Yet no one would dream of calling any of the three the City of Light, and not only because Paris claimed the title a century ago. There’s another, intangible reason. Something about the city’s quality of life, the skeptical outlook of so many residents, and the sparkling yet sardonic essence of Paris, makes the name Ville Lumière ring true. So even if it sounds like a cliché to some, others—including me—will go on using it for as long as the city shines.

Of Cobbles, Bikes, and Bobos