Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light (38 page)

Read Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light Online

Authors: David Downie

Tags: #Travel, #Europe, #France, #Essays & Travelogues

It’s hard to lament the passing of such former neighborhood icons as Génie Burger, the king of grease (it became a Benetton shop, which soon morphed into a shoe boutique, which morphed into an interior decoration shop, and is now probably selling hand-held devices or candy). But even for those with a historical perspective and a wry sense of humor, it’s worrisome when the long-established specialty food shop becomes a Chinese take-out joint, the dry-goods store is reborn as a chain baby accessories boutique, the poultry shop with some of the best chicken in town becomes a second-rate sandwich joint, the florist’s withers into yet another Kookaï (which has morphed several times since), and both the local fishmongers metamorphose into cellular telephone stores—all in a few months. Bat an eye and the flash-in-the-pan boutiques change. The ecosystem’s rules seem to be that once the useful shops of yesteryear have sold out, the infinitely replaceable chains and could-be-anywhere sellers of the desirable but useless continue to roll over. Anyone who witnessed the mom-and-pop disappearing act in America back in the 1960s and ’70s is familiar with the scenario.

One of France’s cult crime-novel writers moved into our building in the early eighties. Tellingly, in the late 1990s he set a series of best-selling books not in the Marais but in the adjacent 11th arrondissement, around the roughshod Oberkampf and Roquette districts. Ironically now the 11th has been thoroughly “tarted up,” as our English friends put it. The real estate agents promote it as “an exciting new extension” of the Marais.

Nostalgia is big business in Paris, but it’s also a subtle poison, usually concocted with vague notions and selective memory. Good news—the “news you can use as you shop,” to quote muckraking reporter Mark Hertsgaard, a fellow San Franciscan—is what makes the world go round. So I try to view the Marais’s current incarnation as a first-time visitor would. It’s certainly a cleaner and quieter place than it has been for a long time, at least in daylight. The hard work and imagination of many business owners must be admired. Their shops, restaurants, and hotels are brighter and more attractive to passersby than were the utilitarian stores and fleabag holes-in-the-wall of pre-gentrification days. The museums—the Picasso, the European photography museum, the Jewish history museum, and others—are magnificent. The restoration jobs done to what were ruins are remarkable. No wonder some of my new

bobo

neighbors honestly believe that those blue-uniformed, corn-paper-Gauloises-smoking ignoramuses of a few decades ago are better off in the suburbs. The Marais was wasted on them.

Happily, there is continuing cause to rejoice as the Marais heads into the 2010s. The three supermarkets, plethora of gourmet convenience stores, gift shops, and hundred-odd chain stores on and around Rue Saint-Antoine haven’t yet killed off our pair of outstanding cheese shops and trios, respectively, of independent wine merchants and bakeries, or the wonderful family-run Au Sanglier, whose devoted chefs make some of the world’s greatest pâtés and premodern cooked dishes to go. Whenever I feel a hint of poisonous nostalgia for the place Georges Simenon described as a “backdrop for a Court of Miracles … swarming with a wretched mob,” I head up to my old office neighborhood in the unwashed, unsung and, frankly, unaesthetic 20th arrondissement. There Algiers meets Beijing via Zanzibar—though the

bobos

aren’t far behind. What does the future hold for the Marais? There might be another French Revolution. More likely, the

bobo

bubble will burst one of these decades. In the meantime the next Marais museum should probably be dedicated to “recent yore.”

Night Walking

In the evening, on the way to visit La Marquise, I intended to walk through the Saint-Séverin graveyard; it was closed. I took the little ruelle des Prêtres and I listened at the gate. I heard some sounds. I sat down to wait in the doorway of the presbytery. After an hour the cemetery gate opened and four youths went out, carrying a corpse in its shroud …

—N

ICOLAS-

E

DME

R

ESTIF DE LA

B

RETONNE

,

Les Nuits de Paris ou Le Spectateur nocturne

, 1788

ight had fallen. Lights began snapping on, illuminating room-by-room the interior of the Île Saint-Louis mansion. Alison and I stood outside, leaning on the parapet above the Seine, and glanced from the dark river to the mansion’s twinkling windows. Tuxedoed men flanked by women wearing gowns mingled under a painted ceiling. Family portraits stared down at the merrymakers, at the maid carrying a silver tray, and out to the quayside where we loitered. A

ight had fallen. Lights began snapping on, illuminating room-by-room the interior of the Île Saint-Louis mansion. Alison and I stood outside, leaning on the parapet above the Seine, and glanced from the dark river to the mansion’s twinkling windows. Tuxedoed men flanked by women wearing gowns mingled under a painted ceiling. Family portraits stared down at the merrymakers, at the maid carrying a silver tray, and out to the quayside where we loitered. A

bateau-mouche

cruised downstream, its lights flooding the tableau vivant above us. One by one the tuxedos and gowns placed their emptied champagne coupes on the maid’s tray and filed out. Chauffeur-driven limousines whisked them away. The maid peered down, spotted us, and pulled the shutters closed with a frown and a snap of both wrists.

By silent accord Alison and I moved on, no longer looking at the river but lifting our eyes instead to the mansions on the island, drawn to their lights like proverbial

papillons nocturnes—

a poetic way to say “moths.” Around the corner from the townhouse a lamp winked on in a cozy mezzanine with low ceilings. There were leather-bound books and brass wall sconces illuminating small oil paintings. We could just make out a liquor cabinet and a stag’s head. Someone moved, casting shadows across the walls. We wondered if the owner was smoking a cigar—as if Alfred Hitchcock, his profile silhouetted, had arisen from the grave.

Soon streetlamps flickered on around us, pooling yellowish light across the stone sidewalks that ring the island. Farther east, facing the Tour d’Argent restaurant, we heard a piano and glanced up to another tiny mezzanine built above a carriage door. A straight-backed piano teacher with her hair in a bun instructed her pupil in what sounded like “Für Elise.” The girl shifted on her stool and played a single bar over and over again before advancing clumsily, battling Beethoven. She wore a hair-band and a long dress with pleats and seemed in that instant the distilled, awkward essence of French bourgeois girlhood.

As we made our way from one pool of lamplight to the next, rounding the island counterclockwise as we often do, we imagined a life story for the girl, for her piano teacher, for the cigar-smoking man with the stag’s head in his apartment, then for the maid with the silver tray and each of the merrymakers from the mansion on the island’s tip.

The

bateaux-mouches

babbled by with commentary in four languages, their floodlights splashing on the façades. Their beams exposed the requisite lovers hidden along the Seine, and revealed interiors with Pompeii-red wallpaper or gaudy chandeliers, decorated ceiling beams, stucco incrustations and seventeenth-century chimney pieces. Glitzy and loud, the tour boats and their searchlights nonetheless transformed banal parked cars or sidewalk benches—and strollers like us—into elements of a magic-lantern show.

The scene flowered in my mind. I began to realize why, in my years in Paris, I have unconsciously loved night walking.

For one thing, daylight flattens and hardens Paris, emphasizing the smog-blackened gray of its plaster façades, the straightness of its boulevards, the maddening symmetry imposed upon it by Baron Haussmann and Napoléon III during the Second Empire.

Night lighting, instead, brings out the bends and recesses, the jagged edges, the secret interiors, the sinuous quality of the Seine, the flying buttresses and other medieval escapees of modernization.

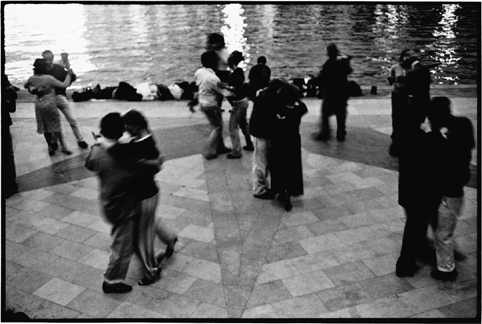

There are practical reasons, too, why nighttime strolling seems to me the finest way to experience Paris nowadays. The later the hour, the thinner the traffic, the cleaner the air, the more quintessential the scenery and atmosphere, stripped of superfluous color and noise. When the cars and trucks and buses and guided groups fade away—unless they’re part of a Paris by Night tour—the city’s magic steals back. Garish Pigalle seems bizarrely wonderful with its sizzling neon signs and fluorescent teeth flashing meretricious smiles. Seen from afar, the Eiffel Tower becomes an eerie glowing skeleton that kicks into life periodically, with swarming, swishing explosions of blue and silver light. Even the Panthéon’s leaden dome appears to hover weightless over the jigsaw puzzle of tin and tile roofs. In winter, when the weather drives Parisians indoors, the nighttime streets and sidewalks are for the taking, and the innocuous voyeurism is unparalleled.

Ever since I had my first twilight epiphany on the Île Saint-Louis more than twenty years ago, I’ve not only been walking more and later at night: I’ve also been searching in literature for references to fellow night-walkers. It seems that

noctambulisme

has a long and noble history in Paris. A strange-sounding word, in English it simply means “sleepwalking.” But in French a

noctambule

is a night owl, someone who literally walks about—very much awake—in the darkness, a denizen of the night, a night-walker, stalker, or prowler. To serve such creatures, the RATP transit authority accommodatingly created the Noctambus: Paris’s late-night bus service whose symbol is an owl.

Everyone knows that Paris is la Ville Lumière—the City of Light. A century or more before it earned that moniker a restless writer named Nicolas-Edme Restif de la Bretonne pioneered the Parisian nighttime prowl. He recorded his adventures from 1786 onward in

Les Nuits de Paris ou Le Spectateur nocturne

, a rambling account of 1,001 nights spread over a period of many years. I was gratified to learn that Restif de la Bretonne’s first and favorite night-walks also began on the Île Saint-Louis when he lived nearby on Rue de Bièvre. Physically at least, the isle must have been much the same then as it is today: most of the townhouses were already 150 years old (they were built in the mid 1600s), the traffic was sparse, the quays cobbled. In Restif de la Bretonne’s day oil lamps with reflectors called

réverbères

hung from the center of the streets casting a feeble glow. As in the rest of central Paris, public lighting on the Île Saint-Louis today is a mix of handsome 1800s lamps and more recent units. The resultant glow entices not only

papillons nocturnes

but also lovers of the island’s Berthillon ice cream.

In my reading and walking I’ve confirmed that no other city cultivates so zealously its nighttime ambience, a sort of luminous identity card spelling out the words

Ville Lumière

. Ever since the term was coined more than a century ago (probably inspired by the 1900 Universal Exposition), artifice is what the City of Light has been all about. Several hundred technicians, engineers, and lighting designers work full-time creating Paris’s magical nighttime kingdom. They follow a master plan that covers the lighting of everything from pedestrian crossings to façades, monuments, and bridges. Lampposts are staggered at studied intervals and heights to produce a luminous blanket. Nothing is left to chance.

Restif de la Bretonne may have invented the genre of nighttime sketches, but to many French people the literary night belongs to Charles Baudelaire. The inveterate noctambulist distilled his shadowy world most notably into

Les Fleurs du Mal

—flowers of evil nourished, with poetic license, not only by the sun but also by the flickering gas lamps of the Second Empire, lamps that lit the wide new sidewalks of Haussmann’s boulevards and the cafés and theaters and railroad stations that sprang up on them, where people came and went at all hours of the day and night in what had become the world’s first modern metropolis. Coincidentally Baudelaire lived on the Île Saint-Louis, at 22 Quai de Béthune (in the Hôtel Lefebvre de la Malmaison), and, later, among the hashish-smokers of the Hôtel de Lauzun (at 17 Quai d’Anjou).

Being able to walk safely at night, under lamps on paved surfaces, was a novelty Baudelaire didn’t take for granted: paradoxically for him it meant the death of his beloved, dark old Paris. Today, many of the cannon-shot boulevards that Baudelaire tramped along, ambivalence in his heart, have been around for nearly 150 years and people now think of them as the quaint old quintessential Paris. I don’t, and rarely include them (with the exception of the boulevards Saint-Germain, Saint-Michel, and Montparnasse) in my nocturnal itineraries. Though some of the grand cafés and theaters of the Second Empire and Belle Époque are still around, the Avenue de l’Opéra, Boulevard Haussmann, and dozens of arteries like them strike me as about the worst places in town for an amble. Even skillful illumination fails to give them charm.