Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light (9 page)

Read Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light Online

Authors: David Downie

Tags: #Travel, #Europe, #France, #Essays & Travelogues

In keeping with its Thousand-and-One-Nights ambience, the latest chapter of the

hôtel

’s history features a Qatari prince. In 2007, Abdullah Bin Abdullah Al Thani bought the landmark, gift-wrapped in red tape, for the equivalent of eighty-eight million dollars, planning to spend nearly as much again on restorations and improvements. It was the “improvements” that led him into a legal labyrinth from which he only began to emerge in 2010, much enlightened.

Baudelaire’s own romantic distractions included installing his mulatto mistress and muse Jeanne Duval, alias the Black Venus, nearby at 6 Rue Le Regrattier. Scratch the surface and seamy stories well up all over the island.

At number 15 Quai de Bourbon, facing the church of Saint-Gervais, the painter and poet Émile Bernard (1868–1941) lived and worked. He founded the Pont-Aven Group of Symbolists. The plaque doesn’t tell you that in his studio, under the gilt beams, court painter Philippe de Champaigne labored in the mid-1600s, his official residence two doors upstream at number 11.

Sculptor Camille Claudel, Rodin’s protégée and mercurial lover, had a ground-floor studio from 1899 to 1913 at number 19 Quai de Bourbon. Islanders still grimace when recalling that, for several months after the movie

Camille Claudel

came out, the sidewalks were impassable because of the mobs paying homage to the mad artist, who died in an asylum. You can’t get into the studio, but you can see one of the sculptures she made here,

Maturity

, an allegory of human mortality, at the Musée d’Orsay.

Another curiosity exhumed from the history books is that the 1659 townhouse capping the Quai de Bourbon goes by the name “House of the Centaur,” because of the pair of low-relief sculptures on the façade showing Hercules fighting Nessus, the savage mythical beast, half man, half horse. For years Madame Louise Faure-Favier held her literary salon here, hosting poet Guillaume Apollinaire, painter Marie Laurencin, writer Francis Carco, and poet Max Jacob, Picasso’s penniless friend. The centaurs overlook a pocket-size park, which is a popular picnic and panoramic spot. Alison and I come here often for the view. The mansion’s current occupants apparently enjoy entertaining. On more than one occasion we have watched as society women in

gowns

and gentlemen in tuxes mingled under a second-floor ballroom’s painted ceiling.

It was this kind of wordly tableau that inspired eighteenth-century author Nicolas-Edme Restif de la Bretonne to invent a new literary genre, the nighttime prowl, writing about it from 1786 onward in

Les Nuits de Paris ou Le Spectateur nocturne

, a rambling account of 1,001 nights on Paris’s streets. His ramblings often started from the Île Saint-Louis (he lived nearby). Taking nighttime walks around the island, with a magic-lantern show of interiors, is my preferred form of voyeurism.

Another, equally fun by day or night, is to poke around the shady courtyards of the island’s largely impenetrable mansions. Electronic coded locks called Digi-codes keep the rabble out. But I’ve discovered two methods to subvert them: wait outside and when someone leaves, confidently stride in, or, two, follow local mail carriers with passkeys on their rounds, starting about ten a.m. Stealth and subterfuge transform innocent exploration into an adventure. They once got me into number 15 Quai de Bourbon after years of cat-and-mouse with the concierge. Hidden in the wide cobbled courtyard I discovered a stone staircase with elaborate ironwork railings. On the roof above rises a two-story gable fitted out with a pulley—presumably to hoist furniture or intruders like me.

By systematically testing the island’s doors I’ve found a few that are nearly always open. The best belongs to the Hôtel de Chenizot, at number 51 Rue Saint-Louis-en-l’Île. Giant griffins uphold a balcony over the studded door. Step in and at the back of the first crumbling court you see a low-relief Rococo floral burst. Keystones carved with heads peer down at you. The rusticated sections of the mansion date to the 1640s. The taller additions are from 1719, when Jean-François Guyot de Chenizot, a royal tax collector from Rouen, redecorated. The building then spiraled downward, becoming, in succession, a wine warehouse, the residence of Paris’s archbishop, a gendarmes’ barracks, a warehouse again, and a moldering apartment house. Today the leprous plaster hides the requisite sweeping staircases and a rear court with a weathered sundial. Though parts of it have been scrubbed, atmosphere still oozes from the place like wet mortar between bricks.

There is a third method I have mastered for penetrating the isle’s inner sancta: take a guided tour. This can turn mystery into mere history, but it’s the only way to get inside the sole townhouse whose interior is accessible to the public, the Hôtel de Lauzun. Here you actually taste a crumb of the upper crust’s lifestyle under the Bourbon Louis—numbers XIII to XVI. The building’s history is lavished upon you, like it or not, by a loquacious cicerone. A potted version of it might run as follows.

Charles Chamois, a military architect, designed the Hôtel de Lauzun in 1657 for a stolid cavalry commissioner named Grüyn. But no horses are to be found: Grüyn’s boar’s-head coat of arms shows up on fireplaces and wall decorations. Much racier a character, the Duc de Lauzun lived here from 1682 to 1684, shacked up with Louis XIV’s first cousin, alias La Grande Mademoiselle. That’s why the Lauzun name stuck.

Surprisingly the townhouse has survived almost intact, naturally without anything the heirs could un-nail and sell, meaning period furniture and original paintings. However, the venerable Versailles parquet creaks satisfyingly underfoot. Several tons of gold glitter from delicately decorated beams and walls, and when light pours through the many-paned windows the effect is blinding. Baudelaire and Théophile Gautier slummed here in the 1840s when the gilding had gone black—no doubt in part because of the hash fumes spewed by adepts of the Club des Hachichins (pronounced Ha-She-Shans). Baudelaire’s hashish-induced hallucinatory poetic visions—of nude women and cloudscapes—apparently derive in part from the mansion’s music room, a salon garlanded with dreamy plasterwork damsels.

Love Conquers Time

was the title given to a second-story ceiling decoration but alas, it has succumbed to the centuries. The catalogue of short-lived unions enacted beneath it, and in the island’s many other similar townhouses, suggests au contraire that Time Conquers All. That’s not a bad motto for the Île Saint-Louis, though I can think of an even better one, given the isle’s ostensibly unchanging qualities—its stony mansions and merry-go-round of wealthy inhabitants. It’s a saying coined by French wit Alphonse Karr in 1849: “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

Montsouris and Buttes-Chaumont: The Art of the Faux

Let us stroll in this décor of desires, this décor filled with mental misdemeanors and with imaginary spasms …

—L

OUIS

A

RAGON

at Buttes-Chaumont,

Paris Peasant

he leaves of the horse-chestnut trees overhanging the sidewalk broke into a sudden jig. Smoke and steam shot through them, puffing up over the tops of the hedges along the street where we were strolling, outside the historic park of Montsouris in Paris’s 14th arrondissement. Alison poked her head through the hedge and beckoned me to follow. I heard a swish and a chug and saw an old black steam engine dive into a tunnel under the park, on the tracks of the Petite Ceinture—theoretically an abandoned railway. A ghost train? I’d read somewhere that back in the nineteenth century those tracks had linked in a loop the outer edge of Paris. I’d also read that they were used occasionally by train buffs to exercise vintage rolling stock.

he leaves of the horse-chestnut trees overhanging the sidewalk broke into a sudden jig. Smoke and steam shot through them, puffing up over the tops of the hedges along the street where we were strolling, outside the historic park of Montsouris in Paris’s 14th arrondissement. Alison poked her head through the hedge and beckoned me to follow. I heard a swish and a chug and saw an old black steam engine dive into a tunnel under the park, on the tracks of the Petite Ceinture—theoretically an abandoned railway. A ghost train? I’d read somewhere that back in the nineteenth century those tracks had linked in a loop the outer edge of Paris. I’d also read that they were used occasionally by train buffs to exercise vintage rolling stock.

By the time Alison and I had ambled across the shady, landscaped curves of Montsouris and dug into our picnic on a lakeside bench, we’d forgotten about the train. The quacking ducks and shifting light, the luxuriant greenery and human parade passing by lulled and enchanted us. There were students from the nearby Cité Universitaire campus and the usual selection of au pairs, plaster-spackled workers in blue dungarees, and tourists shod with running shoes. The gingerbread Pavillon de Montsouris, a restaurant filled with hoity-toity Parisians in their Sunday best, seemed plucked from the proverbial Impressionist painting. So too the oversized prams, the fancy picnic hampers, and the awkward 1870s statuary dotted around us on freshly mowed lawns and raked gravel paths. Exception made for the tourists and joggers, and the cars parked outside the gates, much was as it might have been when the park was built atop abandoned quarries almost a century and a half ago, by Napoléon III’s planners.

Mont Souris

means “Mouse Mountain.” I couldn’t help chuckling at that as we circled the flower-edged knolls covering about forty acres of prime real estate. It seemed an unlikely moniker for the site of an ancient Roman burial ground originally strung along the road leading south from Paris to Orléans. Among the sepulchral monuments once stood the tomb, now lost, of a supposed giant: the gravestone measured about twenty feet long. The giant’s name has come down to us twisted from something now forgotten to Ysorre, Issoire, or possibly the mousy-sounding Souris. “Issoire” lives on in the Avenue de la Tombe-Issoire, a nearby traffic artery.

From the Middle Ages to the late 1860s windmills rose among the ruined tombs and quarries. Nowadays the modest heights of Montsouris sport the parabolic antennae of Paris’s meteorological station. From the park’s belvedere we gazed down and saw a flash of steel—a train rattling over the RER regional express subway tracks. The railway, originally linking Paris to suburban Sceaux, has been here since the inception of Montsouris as a park. The engineers who landscaped the neighborhood used the quarries and the lay of the land to route the trains through almost unnoticed. Those of the Petite Ceinture ran through tunnels even farther underground.

It was the thought of those tunnels that reminded me of the steam train we’d spotted earlier that day. A penny dropped in my head, a rusty handle turned, and I recalled a similar scene in another of my favorite time-tunnel parks, also built on abandoned quarries, Buttes-Chaumont. The event had taken place ten, maybe fifteen years ago, when I’d first stumbled upon the lush Buttes-Chaumont on the opposite side of town in the 19th arrondissement. There too I’d heard a steam train rumbling below, hidden by trees. Irrationally I now wondered if the ghost train we’d seen earlier could possibly be circling Paris, and if we could intercept it across town.

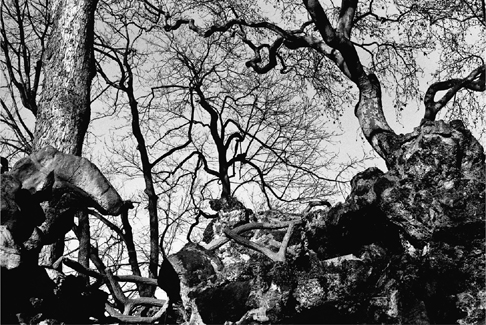

I took Alison by the hand and rushed down Montsouris’s snaky paths to the RER station. We transferred at Gare du Nord then trotted from the Ourcq subway stop to the northern entrance of Buttes-Chaumont. Panting and sweaty like the droves of joggers on the park’s paths, we found the footbridge over the Petite Ceinture. Did we see the old black steam train conveniently chuff by? Of course not. But as I leaned on the bridge’s iron grilles catching my breath amid swerving perambulators, swinging picnic baskets, and bourgeois families seemingly whisked along behind us from Montsouris, I was glad to have been so impulsive. Though the scene around us was in living color—a riot of blossoms and garish outdoor casual wear—my mind’s eye focused on a sepia-tinted image from the Second Empire circa 1865.

In it there were brand new boulevards lined by balconied buildings, and as many smokestacks as church towers on the surprisingly familiar horizon. It was an image my brain had clicked on and dragged from the novels of Zola and Balzac, the poetry of Baudelaire, the photography of Charles Marville—official photographer to Napoléon III and Haussmann. Welling up from it I could almost smell the electrifying greed of the Second Empire’s new bourgeoisie, a perfume powerful enough to overwhelm the cabbage-scented misery of the hundreds of thousands of peasants pouring into town, seeking their fortune amid the smokestacks. How might it have felt to wake up in Paris one day in the 1860s to discover a new city had mushroomed overnight, with not only new roads and buildings and parks like Montsouris and Buttes-Chaumont, but also a new soul, a new way of living—the birth of the modern?