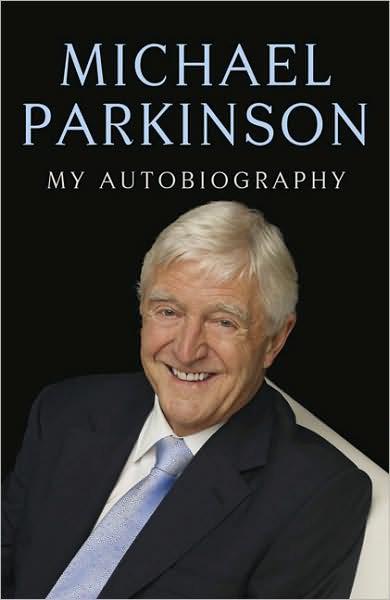

Parky: My Autobiography

PARKY

MY AUTOBIOGRAPHY

Michael Parkinson

HODDER & STOUGHTON

Copyright © Michael Parkinson 2008

1

The right of Michael Parkinson to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Epub ISBN 978 1 84456 900 7

Hardback ISBN 978 0 340 96166 7

Trade paperback ISBN 978 0 340 97680 7

Hardback ISBN 978 0 340 96166 7

Trade paperback ISBN 978 0 340 97680 7

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

This book celebrates

the memory of my parents, the love of Mary,

the blessing of our sons Andrew, Nicholas and Michael

and the joy of our grandchildren, Emma, Georgina and Ben;

Laura and James; Honey, Felix and Sophia.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My special thanks to Erin Reimer and my son Michael for their dedicated research and intelligent prompting; to Teresa Rudge for her patience and skill in making sense of an untidy manuscript; to Andrew Bullock for his enthusiastic support; and to my former PA Autumn Phillips for causing a much-needed break from writing with a royal wedding! Also to my son Nicholas for finding me a typewriter (and some ribbons) in America thereby frustrating my last feeble excuse for not writing the book; and to Mo, Michael, Dom and the rest of the staff at the Royal Oak in Paley Street for the marvellous sustenance. Finally, warm thanks to Roddy Bloomfield, my editor at Hodder & Stoughton, who has nursed the book through decades of uncertainty.

Then there are the stalwarts who worked hard on the

Parkinson

show but didn’t get a mention in the narrative simply because there wasn’t the space. They are Graham Lindsay, Gill Stribling-Wright, Christina Baker and Lynda Wood and, in particular, Quentin Mann who, as floor manager, guided me through near on 600 shows and never let me down.

Parkinson

show but didn’t get a mention in the narrative simply because there wasn’t the space. They are Graham Lindsay, Gill Stribling-Wright, Christina Baker and Lynda Wood and, in particular, Quentin Mann who, as floor manager, guided me through near on 600 shows and never let me down.

I would also like to thank friends and colleagues who were interviewed for the book and gave so generously of their time: Anthony Howard, Harry Whewell, Michael Frayn, Barrie Heads, Brian Armstrong, Chris Menges, Johnnie Hamp, Leslie Woodhead, Sir Paul Fox, the late Sir Bill Cotton, Cecil Korer, Eve Lucas, Jill Drewett, John Fisher, Kate Greer, Patricia Houlihan, Roger Ordish, Chris Greenwood, Colin McLennan, David Lyle, David Mitchell, Greg Coote, Bea Ballard, George Morton, Jim Moir, Anthony Cherry, Sir David Frost, Steven Lappin and Robin Esser.

Other helpful people and organisations were: Jeff Walden/BBC Written Archives Centre, Stuart Craig/Bishop Simeon Trust, Simon Hoggart, Jarvis Astaire, Mirrorpix, News International Archives, The

Guardian

Newsroom Archive Centre, Parliamentary Archives, The London Library, ITN Source, BBC Motion Gallery,

Desert Island Discs

, ITV Press Office, Cutting it Fine, ABC Library/Australia, National Film and Sound Archives/Australia and the

Daily Telegraph.

Guardian

Newsroom Archive Centre, Parliamentary Archives, The London Library, ITN Source, BBC Motion Gallery,

Desert Island Discs

, ITV Press Office, Cutting it Fine, ABC Library/Australia, National Film and Sound Archives/Australia and the

Daily Telegraph.

And, finally, looking back at what I have written I am aware I have failed to mention lifelong friends including Carol and Marshall Bellow, of Leeds, and Athol and Jean Carr, who live in Rotherham, whose friendship and loyal support over the years has been a treasured gift to all our family.

PREFACE – THE CHOICE

Every morning, when I woke, I could see the pit from my bedroom window. When you couldn’t see it you could smell it, an invisible sulphurous presence. It was where my dad worked, where my granddad worked and his dad before him. It was where I expected to end up. I remember thinking it wouldn’t bother me, providing I could marry Ingrid Bergman and get a house much nearer the pit gates. Shortly after Vesting Day, when Attlee’s government nationalised the mines, we were taken from Barnsley Grammar School to visit a colliery. When I arrived home my father asked me where we had been. I told him. He said, ‘That’s not a pit, it’s a holiday camp.’

He told me to be ready, 4 a.m. the following Sunday, and he would show me what a real coal mine was like. He took me down Grimethorpe Colliery and tipped the wink to his mate on the winding gear that there was a tourist on board. We dropped like a man without a parachute. Big laugh. The rest wasn’t so funny. He took me where men worked on their knees getting coal, showed me the lamp he used to test for methane gas, explained how dangerous it was. He showed me the pit ponies. The only time I had seen them before was when they had their annual holiday from their work underground and emerged from the dark, their eyes bandaged against the light.

We stood in front of a seam of coal, black and shiny. ‘Let’s see if you’d make a miner,’ he said. He gave me a pick and nodded at the seam. The harder I hit the coal, the more the pick bounced off the surface. ‘Find the fault,’ he said, running his fingers across the coal face. He tapped it and a chunk fell out, glittering in his lamplight. We walked back and he said nothing until we reached the pit gates. ‘What do you reckon?’ he said.

‘You won’t get me down there for a hundred quid a shift,’ I said.

He nodded and smiled. ‘That’s good,’ he said, ‘but be warned that if ever you change your mind and I see you coming through those gates I’ll kick your arse all the way home.’

This is a story of a child who did as he was told.

1

PIT VILLAGE

My father used to love coming to the show, although he was never quite sure that what I was doing was a proper job. He wanted me to be a professional cricketer. Just before he died he said to me: ‘You’ve had a good life, lad.’ I said I had. ‘You’ve met some fascinating people and become quite famous yourself,’ he said. I nodded. ‘What is more, you’ve made a bob or two without breaking sweat,’ he said. I agreed. ‘Well done,’ he said.‘But think on, it’s not like playing cricket for Yorkshire, is it?’ That may well be true, but once or twice it got pretty darned close.

From the script of the final

Parkinson Show

recorded at the London Studios, 6 December 2007

Parkinson Show

recorded at the London Studios, 6 December 2007

When I was born in 1935 my father wanted me called Melbourne Parkinson because we had just won a Test match there. My mother, a woman of great common sense, put her foot down. Her winning argument was that my father could have his way if she could pick a second name. He was agreeable until she told him that she wanted me called Gershwin after her favourite composer. They settled for Michael.

I was born on a council estate in Cudworth, a mining village in the South Yorkshire coalfield. In those days it was nicknamed ‘Debtors’ Retreat’ and my dad told me the rent collectors walked around in pairs. He was a miner at Grimethorpe Colliery. Every day he would walk three miles to his place of work, spending eight hours underground getting coal. He was paid seven shillings a shift.

The year after I was born a dispute at the pit ended, as disputes did in those days, with a lockout. The management simply closed the pit gates until the miners, having learnt their lesson, went back to work. Fed up with the mining industry, seeking a less uncertain career, father borrowed a fiver from a relative and went to Oxford to get a job on the new Morris Motors car assembly line. The day after the interview, walking around Oxford waiting to see if he had been accepted, he felt a terrible longing for his native landscape, so he came home. A week later a letter arrived telling him the job was his if he wanted it.

My mother, Freda, was in favour of a move. She had been born in Oxford. Her father was killed in France in the First World War. She arrived in Yorkshire not out of choice but by chance. After her husband’s death, my grandmother would visit a local hospital where the casualties of war were left outside in their wheelchairs awaiting anyone kind enough to take them for a walk. One day she took Fred Binns for a spin. He had been invalided out of the army after being wounded on the Western Front. Lodged in the back of his shoulder was a spectacular lump of metal, which surgeons deemed too risky to remove. Later on, when he became my grandmother’s second husband and took her family back to his native Yorkshire, he would allow me, as a Christmas treat, to feel the shrapnel in his back.

‘How did it happen?’ I’d say. ‘That would be telling,’ he would reply, the longest sentence I ever heard him speak and the only time he ever mentioned the war.

My mother always said she wasn’t really a Yorkshire woman, more a transplant. Living in a pit village, being married to a miner, was not how she had imagined her life. In an unfinished family history, which she started writing after the death of my father, she explains her frustration:

My older brother Tom was a bright boy. He won a scholarship to Grammar School. My parents borrowed £100 from a local money lender to send him there. They paid 66 per cent interest. They were still paying it off when I was pulled out of school to look after my mother who was unwell. I wanted to be a designer. I had a flare for making clothes. I dreamed of a life in a street of doctors and professional people. I imagined marrying a teacher.

Throughout her life she never lost her belief that she had been thwarted in her ambitions, that she was unfairly cheated of an opportunity to prove her talent. But I don’t want to portray her as a bitter person, as someone soured by disappointment. Quite the opposite. She channelled her ambitions through her son, found great joy and fulfilment in her grandchildren and, most of all, never had occasion to doubt the profound and enduring love of a good man.

Even though she said she would never marry a miner, she reckoned without John William Parkinson. He was ten years older than my mother and the best friend of her brother. She was twelve when she first became aware of him. He was one of sixteen children, ten of whom survived infancy.

His father, Sammy, was a miner, like his dad before him. And, like his dad, Sammy was a black-backed miner. These men believed that excessive washing of the back weakened the muscles needed to take the weight of a collapsing seam. They washed their backs once a week, no more.

I remember seeing my granddad with his strange discoloured back, sitting in the tub in front of the fire while his wife and daughters took turns to fill it from a brick-built copper in the corner of the room. Before pithead baths sons would follow fathers into the water in order of seniority. Women and children witnessed the ritual. Modesty was not something the working class could afford. When pithead baths eventually arrived and his sons started using them, Sammy stuck by his home ritual. Even a serious accident when he was buried in a fall and suffered severe injuries didn’t change his attitude. When they dug him out he had deep lacerations to the top of his head. In later life, when his hair turned white, the scars showed through like veins in a leaf.

Other books

What a Woman Needs by Judi Fennell

Marta's Legacy Collection by Francine Rivers

In the Line of Duty: First Responders, Book 2 by Donna Alward

Weaving the Strands by Barbara Hinske

Rise and Shine (Shine On Series, Book 2) by Jewell, Allison J.

A Haunted Theft (A Lin Coffin Mystery Book 4) by J A Whiting

Smart Women by Judy Blume

Claiming His Fate by Ellis Leigh

Playland by John Gregory Dunne

Open For Him (BBW / Billionaire Erotic Romance) by James, Karolyn