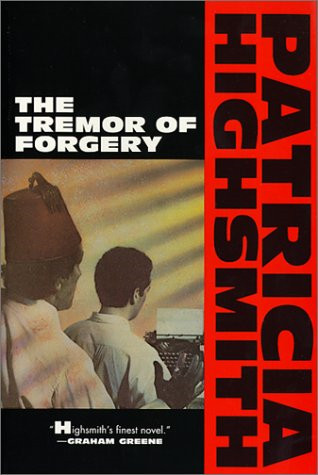

Patricia Highsmith - The Tremor of Forgery

Read Patricia Highsmith - The Tremor of Forgery Online

Authors: Patricia Highsmith

Patricia Highsmith

The Tremor of Forgery

1969

For Rosalin

d Constable as a small souvenir

of a rather long friendship

‘

You

’

re

sure there

’

s no letter for me?

’

Ingham asked.

“

Howard Ingham. I-n-g-h-a-m.

’

He spelt it, a little uncertainly, in French, though he had spoken in English.

The plump Arab clerk in the bright red uniform glanced through the letters in the cubbyhole marked I-J, and shook his head.

‘

Non, m

’

sieur.

’

‘

Merci,

’

Ingham said with a polite smile. It was the second time he had asked, but it was a different clerk. He had asked ten minutes ago when he arrived at the Hotel Tunisia Palace. Ingham had hoped for a letter from John Castlewood. Or from

I

n

a. He had been away from New York five days now, having flown first to Paris to see his agent there, and just to take another look at Paris.

Ingham lit a cigarette and glanced around the lobby. It was carpeted with oriental rugs, and air-conditioned. The clientele looked mostly French and American, but there were a few rather dark-faced Arabs in Western business suits. The Tunisia Palace had been recommended by John. It was probably the best in town, Ingham thought.

He went out through the glass doors on to the pavement. It was early June, nearly 6 p.m., and the air was warm, the slanting sunlight still bright. John had suggested the

Café de Paris for a pre-lunch or

dinner drink, and there it was, across the street and at the secon

d corner, on the Boulevard Bour

guiba. Ingham walked on to the boulevard, and bought a Paris

Herald-Tribune.

The rather broad avenue had a tree-bordered, cement-paved division down its middle on which people could walk. Here were the newspaper and tobacco kiosks, the shoeshine boys. To Ingham, it looked something

between a Mexico City street and a Paris street, but the French had had a hand in both Mexico

Ci

ty and Tunis. Snatches of shouted conversation around him gave him no clue as to meaning. He had a phrase book called

Easy Arabic

in one of his suitcases at the hotel. Arabic would obviously have to be memorized, because it bore no relation to anything he knew.

Ingham walked across the street to the Caf

é

de Paris. It had pavement tables, all occupied. People stared at him, perhaps because he was a new face. There were many Americans and English, and they had the expressions of people who had been here some time and were a little bored. Ingham had to stand at the bar. He ordered a Pernod, and looked at his newspaper. The place was noisy. He spotted a table and took it.

People idled along the pavement, staring at the equally blank faces in the

café

. Ingham watched especially the younger people, because he was on an assignment to write a film script about two young people in love, or rather three, since there was a second young man who didn

’

t get the girl. Ingham saw no boy and girl walking along, only single young men or pairs of boys holding hands and talking earnestly. John had told Ingham about the closeness of the boys. Homosexual relationships had no stigma here, but that had nothing to do with the script. Young people of opposite sex were often chaperoned or at least spied upon. There was a lot to learn, and Ingham

’

s job in the next week or

s

o

until

John arrived was to keep his eyes open and absorb the atmosphere. John knew a couple of families here, and Ingham would be able to see inside a middle-class Tunisian home. The story was to have the minimum of written dialogue, but still something had to be written. Ingham had done some television writing, but he considered himself a novelist. He had some trepidations about this job. But John was confident, and the arrangements were informal. Ingham had signed nothing. Castlewood had advanced him a thousand dollars, and Ingham was scrupulously using the money only for

business expenses. Quite a bit of it would go on the car he was supposed to hire for a month. He must get the car tomorrow morning, he thought, so he could begin looking around.

‘

Merci, non

,’

Ingham said to a

peddler

who approached him with a long-stemmed, tightly bound flower. The over-sweet scent lingered in the air. The

peddler

had a handful, and was pushing about among the tables yelling,

‘

Yes-

meen?

’

He wore a red fez and a limp, lavender jubbah so

thin

one could see a pair of whitish underpants.

At one table, a fat man twiddled his jasmine, holding the blossom under his nose. He seemed in a trance, his eyes almost crossed with his daydream. Was he awaiting a girl or only thinking of one? Ten minutes later, Ingham decided he was awaiting no one. The man had finished what looked like a colourless soda pop. He wore a light grey business suit. Ingham supposed he was middle-class, even a bit upper. Perhaps he made thirty or more dinars per week, sixty-three dollars or more. Ingham had been boning up on such things for a month. Bourguiba was tactfully trying to extricate his people from the reactionary bonds of their religion. He had abolished polygamy officially, and disapproved of the veil for women. As African countries went, Tunisia was the most advanced. They were trying to persuade all French businessmen to leave, but still depended to a great extent on French monetary aid.

Ingham was thirty-four, slightly over six feet tall, with light brown hair and blue eyes, and he moved rather slowly. Although he never bothered about exercise, he had a good physique with broad shoulders, long legs and strong hands. He had been bo

rn

in Florida, but considered himself a New Yorker, because he had lived in New York since the age of eight. After college

—

the University of Pennsylvania- he had worked for a newspaper in Philadelphia and written fiction on the side, without much luck

until

his first book,

The Power of Negative Thinking,

a rather flippant and juvenile spoof of positive thinking, in which his pair of negative-

thinking heroes emerged covered in glory, money and success. On the strength of this, Ingham had quit journalism, and had had two or three rocky years. His second book,

The Gathering Swine,

had not been so well received as the first book. Then he had married a wealthy girl, Charlotte Fleet, with whom he had been very much in love, but he had not availed himself of her money, and her wealth in fact had been a handicap. The marriage had ended after two years. Now and again, Ingham sold a television play or a short story, and he had kept going in a modest apartment in Manhattan. This year, in February, he had had a breakthrough. His book

The Game of

‘

If’

had been bought for a film for $50,000. Ingham suspected it had been bought more for th

e

crazy love story in it than for its intellectual content or message (the necessity and validity of wishful thinking), but n

o

matter, it had been bought, and for the first time Ingha

m

was enjoying a taste of financial security. He had declined a

n

invitation to write the film script of

The Game of

‘

If

’

.

He thought film scripts, even television plays, were not his forte, and

The Game

was a difficult book for him to think of in film terms.

John Castlewood

’

s idea for

Trio

was simpler and more visual. The young man who didn

’

t get the girl married someone else, but wreaked vengeance on his successful rival in a most horrible way, first seducing his wife, then ruining the husband

’

s business, then seeing that the husband was murdered. Such things could scarcely happen in America, Ingham supposed, but this was in Tunisia. John Castlewood had enthusiasm, and he knew Tunisia. And John had known Ingham and had invited him to try the script. They had a producer named Miles Gallust. Ingham thought that if he felt he wasn

’

t getting anywhere, wasn

’

t capable, he would tell John, give back the thousand dollars, and John could find someone else. John had done two good films on small budgets, and the first,

The Grievance,

had had the better success. That had been set in Mexico. The second had been

about Texas oil-riggers, and Ingham had forgotten the title. John was twenty-six, f

ul

l of energy and the kind of faith that went with not knowing much about the world as yet, or so Ingham thought. Ingham felt that John had a future better, more than likely, than his own would be. Ingham was at an age when he knew his potentialities and limitations. John Castlewood did not know his as yet, and perhaps was not the type ever to think about them or recognize them, which might be all to the good.

Ingham paid his bill, and went back to his hotel room for a jacket. He was getting hungry. He glanced again at the two letters in the box marked I-J, and at the empty cubbyhole under his hanging key.

‘Vingt-six, s’il vous plaît,’

he said, and took the key.

Again taking John

’

s advice, Ingham went to the Restaurant du Paradis in the rue du Paradis, which was between his hotel and the Caf

é

de Paris. Later, he wandered around t

he town, and had a couple of c

af

é

expr

è

s standing at counters in

c

af

é

s where there were no tourists. The patrons were all men in these places. The barman understood his French, but Ingham did not hear anyone else speaking French.

He had thought to write a letter to Ina when he got back to his hotel, but he felt too tired, or perhaps uninspired. He went to bed and read some of a William Golding novel

that

he had brought from America. Before he fell asleep, he thought of the girl who had flirted with him

—

mildly

—

in the

Caf

é

de Paris. She had been blonde, a trifle chubby, but very attractive. Ingham had thought she might be German (the man with her could have been anything), and he had felt pleased when he heard her talking French with the man as they went out. Vanity, Ingham thought. He should be thinking about Ina. She was certainly thinking about him. At any rate, Tunisia was going to be a splendid place not to think any more about Lotte. Thank God, he had almost stopped. It had been a year and six months since his divorce, but sometimes to Ingham it seemed like only six months, or even two.

The

next morning, when there was again no letter for him, it occurred to Ingham that John and Ina might have written to him at the Hotel du Golfe in Hammamet, where John had suggested he should stay. Ingham had not yet made a reservation there, and he supposed he should for the 5 th or 6th of June. John had said, Took around Tunis for a few days. The characters are going to live in Tunis…. I don

’

t think you

’

d like to work there. It

’

ll be hot, and you can

’

t swim unless you go to Sidi Bou Said. We

’

ll work in Hammamet. Terrific beach for an afternoon swim, and no city noises….

’