Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

Paul Revere's Ride (20 page)

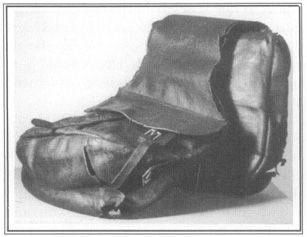

Paul Revere’s leather saddlebags are in the collections of the Paul Revere Memorial Association, Boston.

Suddenly the mood was shattered. It would have been the horse that noticed first, as horses often do. A rider as experienced as Paul Revere would instantly have seen the animal’s head come up, and her ears prick forward, and her high-arched neck twist slightly from side to side as she came alert to danger. He would have felt a momentary break in the rhythm of the canter, a change in the tension of the reins, and a subtle shift of pressure beneath his seat.

Paul Revere searched the road ahead. Suddenly he saw two horsemen in the distance, almost invisible, waiting silent and motionless in the moonshadow of a great tree by the edge of the highway. As Revere rode closer, he made out the blur of military cockades on their hats, and the bulge of heavy holsters at their hips.

Regulars!

He pulled sharply on his reins, and Deacon Larkin’s horse responded instantly. Even before she had stopped, Revere yanked

her head around, and spurred her savagely in the opposite direction. The two officers gave chase. One tried to cut off Paul Revere by riding crosscountry, and galloped straight into an open claypit, miring his horse in the wet and heavy ground. The other kept to the road, but was soon left far behind by the long stride of Deacon Larkin’s splendid mare.

As his pursuers disappeared in the darkness behind him, Paul Revere later recalled that he “rid upon full gallop for the Mistick road.” His route took him to a small village north of Charlestown which is now the Boston suburb of Medford. It was commonly called Mystic in 1775, after the river of the same name. He had not planned to go that way. This road was a long detour for him, and added many northern miles to his westward journey. He must have cursed his luck. But as Prince Otto von Bismarck liked to observe, there is a special Providence for children, fools, drunkards—and the United States of America! Paul Revere’s unwelcome detour took him safely around the roving British patrols that might have intercepted him.

Revere followed the Mystic Road over a wooden bridge, and clattered into the quiet village. From there he rode through north Cambridge to the little hamlet of Menotomy, now the town of Arlington. At the Cooper Tavern in Menotomy he met the King’s Highway or Great Road, as it was variously called, and turned west toward Lexington. He continued along the road through rising hills to the town’s meetinghouse at Lexington Common. There he came to the Buckman Tavern with its traditional bright red door. Perhaps still burning in the window was a small metal lantern with four candle stubs that signaled the availability of food, drink, lodging, and livery.

41

At the Buckman Tavern, Paul Revere turned right into the Bedford Road. He traveled a few hundred yards past a fifty-acre tract of the minister’s farmland to the parsonage that was the home of Lexington’s clergyman, Jonas Clarke, his wife and many children.

42

Inside the crowded house that night were at least ten Clarkes, and Sam Adams and John Hancock. With them were Hancock’s “slight and sprightly” fiancee Dorothy Quincy, and his aged aunt Lydia Hancock. The Clarkes and Hancocks were kin. They were both old clerical families, deeply rooted in the extended cousinage of New England Congregationalism. John Hancock and his ladies had been there since April 7; Sam Adams since April 10.

43

Everyone in the parsonage had retired for the night. Adams

and Hancock were sleeping in the downstairs parlor-bedroom. Aunt Lydia and Miss Dolly had the best chamber upstairs. Jonas Clarke and his wife were in another bedroom, and eight of their twelve children were in various trundle beds and backrooms. The old house was dark and silent. Outside, the faithful Sergeant William Munroe stood guard in the moonlight with ten or twelve Lexington militiamen.

44

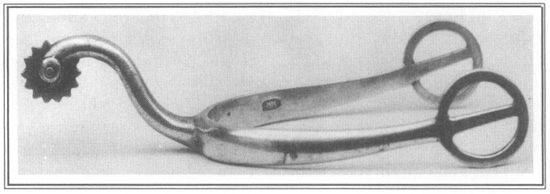

It was midnight when Paul Revere arrived, his horse probably flecked with foam and streaked with blood from the sharp rowels of his old-fashioned silver spurs. The scene that followed was not the heavy melodrama that one expects of great events, but a touch of low comedy that often incongruously happens in moments of high historical tension.

When Paul Revere came riding up to the parsonage, he met Sergeant William Munroe and called out to him in a loud voice. Sergeant Munroe did not know Paul Revere, and was not impressed by the appearance of this midnight messenger. In the eternal manner of sergeants in every army, he ordered Revere not to make so much noise—people were trying to sleep!

“Noise!” Paul Revere answered, “You’ll have noise enough before long! The Regulars are coming out!”

The alert reader will note what Paul Revere did

not

say. He did not cry, “The British are coming,” Many New England express riders that night would speak of Regulars, Redcoats, the King’s men, and even the “Ministerial Troops,” if they had been to college. But no messenger is known on good authority to have cried,

“The British are coming,” until the grandfathers’ tales began to be recorded long after American Independence. In 1775, the people of Massachusetts still thought that

they

were British. One of them, as we shall see, when asked why he was preparing to defend his house, explained, “An Englishman’s home is his castle.” The revolution in national identity was not yet complete.

45

In American museums, Paul Revere spurs are as numerous as fragments of the True Cross. This one may be authentic. It is made of silver, bears the mark of Paul Revere, and is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. There is no evidence that Revere actually wore it, but he is known to have used spurs on his midnight ride, probably a pair of his own manufacture such as this one. Its sharp rowls would have left the flanks of his horse raw and bloody.

On the other side, the Regulars did not usually refer to the New England militia as Americans, but as “country people,” “provincials,” “Yankeys,” “peasants,” “rebels,” or “villains” in the

Oxford English Dictionary’s

definition of “a low-born, base-minded rustic,” or “boors” in the archaic sense of farmer (as Dutch

boer).

As late as 1775, people on both sides in this great struggle still thought of themselves as of the same stock. They commonly spoke of their conflict not as the American Revolution, but as a “Civil War” or “Rebellion” that divided English-speaking people from one another. This was the way that Paul Revere was thinking on April 18, 1775, when he told Sergeant Munroe that the “Regulars are coming out.”

46

After exchanging a few choice words with the sergeant, Paul Revere went past him and banged heavily on the door of the parsonage. Up flew the sash of a bedroom window, and out popped the leonine head of the Reverend Jonas Clarke, perhaps wearing a long New England night cap. Other heads appeared from different windows—as many as ten Clarke heads in various assorted sizes. From yet another downstairs window emerged the heads of Sam Adams and John Hancock, who instantly recognized their midnight caller. “Come in, Revere,” Hancock called in his irritating way, “we’re not afraid of

you.”

47

Paul Revere entered the Clarke house in his spurs and heavy riding boots, his long mud-spattered surtout swirling around him. He delivered his message to Hancock and Adams. The hour was a little past midnight. The men began to talk urgently among themselves. Revere asked if Dawes had arrived, and was concerned to hear that nobody had seen him. “I related the story of the two officers,” Revere later recalled, “and supposed he must have been stopped, as he ought to have been there before me,” Half an hour later, to everyone’s relief, Dawes appeared with a duplicate of the message from Boston.

The two expresses remained in Lexington for another hour. “We refreshed ourselves,” Revere wrote simply. Dorothy Quincy remembered later that John Hancock left the parsonage and walked down the Bedford Road to the tavern on the Common,

where some of the Lexington militia had been staying the night. Sam Adams went along, as did the minister Jonas Clarke. Probably Revere and Dawes also went to the tavern to find “refreshment” for themselves, and their exhausted horses.

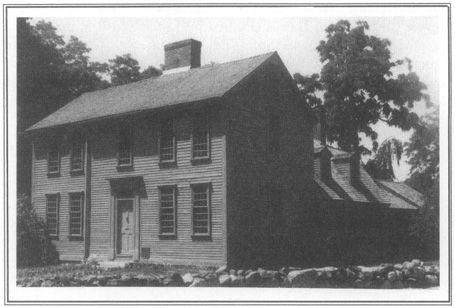

The Hancock-Clarke Parsonage was built in 1738 for Lexington’s minister John Hancock. In 1775, it was occupied by his successor Jonas Clarke, whose silhouette still hangs in the house. Samuel Adams and John Hancock (grandson of the builder) were staying here when Paul Revere arrived with news that the "Regulars are out." The house was moved across the street in 1896, and returned to its original location in 1974,

The men talked with members of Lexington’s militia company. Jonas Clarke remembered that the conversation centered on the purpose of the British mission. They agreed on reflection that Doctor Joseph Warren must have been mistaken in thinking that the purpose of General Gage was the arrest of Hancock and Adams. It was true, as Jonas Clarke observed, that “these gentlemen had been frequently and publickly threatened.” But the arrest of Hancock and Adams alone could not be the primary object of so large an expedition. “It was shrewdly suspected,” Clarke later recalled, “that they were ordered to seize and destroy the stores belonging to the colony, then deposited at Concord.”

48

It was clear that Concord must be warned, and that the messengers

from Boston were the men to do it. Once again, Paul Revere and William Dawes climbed into their saddles, probably a bit more slowly than before. They said farewell to Adams and Hancock, and turned the heads of their weary horses westward toward the Concord Road. Behind them, Lexington’s town bell began to ring in the night.

The Ordeal of the British Infantry

The Ordeal of the British Infantry