Pediatric Primary Care (40 page)

E. Differential diagnosis. Careful history will determine the type of injury and degree of burn. Other diseases include scalded skin syndrome and Ritter's disease.

F. Treatment. Management depends on the classification of the burn. Electrical and chemical burns usually require hospital observation. Injuries with associated upper airway injury, fractures, abuse, or severe pain also should be hospitalized. Outpatient treatment includes maintenance of proper nutrition. Superficial burns are treated with cool compresses and pain management. Partial thickness burns are treated with daily cleansing, debridement of devitalized tissue, application of silver sulfadiazine cream, bacitracin, or gentamycin ointment, and a thin guaze dressing, as well as appropriate pain management.

G. Follow up. Treatment should continue for 1 to 2 weeks, or until wounds are healed. Assessment for infection should continue.

H. Complications. Local infection and inflammation, as well as neurologic and vascular compromise.

I. Education. Home and environmental safety issues should be addressed, firstaid measures, proper use of sunscreen to prevent sunburn of the affected areas. The extent of scarring is difficult to predict, depending on the severity and extent of the burn, whether grafting was needed, and skin color.

IV. DIAPER DERMATITIS

A. Etiology. Diaper dermatitis is an inflammation of the skin in the diaper area due to breakdown of the skin's natural barrier.

B. Occurrence. Diaper dermatitis is perhaps the most common skin disorder seen under 2 years of age. If not properly controlled, diaper dermatitis can recur regularly until toilet training is complete.

C. Clinical manifestations. Causes of diaper dermatitis include irritant secondary to prolonged contact with urine and feces,

Candida albicans

, bacterial infections including impetigo secondary to staphylococcus or streptococcus, and psoriasis.

D. Physical findings.

1. The most prevalent form of diaper dermatitis is irritant dermatitis. Usually confined to the buttocks, perineal area, and medial thighs, sparing the interiginous areas. Contributing factors are prolonged time between diaper changes, harsh soaps, improper moisturization, use of barrier ointments, and excessive heat in warm climates.

2. Candidal diaper dermatitis should be suspected when a diaper rash does not respond to topical treatments. It is a common occurrence with the use of oral antibiotics.

3. Characterized by erythema on the buttocks, suprapubic area, and medial thighs with raised edges with sharply demarcated margins with pinpoint satellite lesions surrounding the borders.

4. Impetigo is characterized by flaccid vesicles and bullae on the lower abdomen, medial thighs, and buttocks.

5. Psoriasis is a violaceous plaque with adherent silvery-white scale. Borders are sharply demarcated.

E. Diagnostic tests. Microscopic examination with KOH will reveal budding yeasts with hyphae in Candidal infections. Bacterial culture of a vesicle or crust will diagnose bacterial infection. See

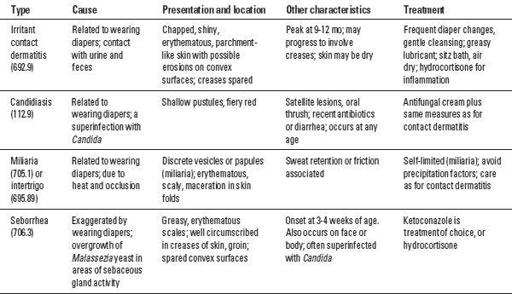

Table 20-3

.

F. Treatment.

1. Irritant diaper dermatitis is treated with frequent diaper changes, cleansing the skin with a mild cleanser, drying the skin, and applying a barrier such as petrolatum or Aquaphor. Air drying between changes is also helpful.

Table 20-3

Diagnosis and Treatment of Diaper Dermatitis (691.0)

2. Candidal rashes should be treated with topical antifungal medications. Avoid topical corticosteroid ointments, including combination antifungal and corticosteroid medications to reduce the possibility of atrophy in an occluded area. Resistant infections should be treated with appropriate oral antifungal medications.

3. Bacterial infections should be treated with appropriate antibiotics. Infections that include a large proportion of the diaper area are best treated orally. Isolated areas may be treated appropriately with topical antibiotics, such as Mupirocin.

4. Psoriasis is a chronic condition. Topical steroid ointment should be applied twice daily for 2-week periods. Ointments such as petrolatum or Aquaphor can be used at diaper changes. Watch for psoriatic plaques in other areas, as well as psoriatic arthritis.

G. Complications. Resistant infections.

H. Education. Parents should be taught proper skin cleansing, frequent diaper changes, and proper use of barriers to prevent contact of urine and stool with skin.

V. RASHES

A. Allergic, contact: See Atopic Dermatitis.

VI. INFESTATIONS: PEDICULOSIS

A. Etiology and occurrence. Pediculosis or lice are spread from human to human, and epidemics are common in schoolchildren. Pediculosis corporis is often found in crowded living conditions and areas of poor personal hygiene.

B. Clinical manifestations and physical findings. Nits (louse eggs) are found in the hair on the scalp. Pediculosis corporis begins as small papules with secondary lesions developing from scratching, resulting in crusted papules and ulcerations.

C. Diagnostic tests. White nits are obvious on the hair shaft. A hair may be plucked and microscopic examination will reveal nits. Pediculosis corporis is diagnosed by examination of the seams of the clothing, which reveals the louse.

D. Differential diagnosis. Atopic dermatitis or other eczematous dermatitis, as well as scabies.

E. Treatment. Remove nits with a fine-tooth comb after soaking in vinegar or over-the-counter products such as Nix Crème Rinse, Rid, and Acticin. A second application of these agents is recommended in 7-10 days. Shaving the affected area is not necessary. Also can use dryer sheets to remove nits.

F. Complications. Atopic dermatitis secondary to pruritus and reaction to nits and eggs. Treat with appropriate topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.

G. Education. Proper use of topical medications and proper use of nit comb. Application of gasoline is not an accepted treatment and must be avoided.

VII. SCABIES

A. Etiology and occurrence. An infestation caused by

Sarcoptes scabiei.

Usually spread by skin-to-skin contact among household members and by sexual contact. The fertilized female mite burrows in the stratum corneum, laying eggs and feces which create irritation and pruritus.

B. Physical findings. Pinpoint vesicles and erythematous papules in S-shaped pattern. Finger webs, flexor wrists, areola, umbilicus, waist-band area, groin, and axilla are common sites of lesions. Children and adults rarely have lesions above the neck. Infants can manifest lesions on the palms and soles. Incubation from infestation to onset of symptoms is usually 1 month, with nocturnal itching most intense.

C. Diagnostic tests. Mineral oil applied to the vesicle, scraped with a No. 15 blade and placed on a slide with a cover slip reveals mites, eggs, or feces on microscopy.

D. Differential diagnosis. Insect bites, atopic dermatitis, drug eruptions.

E. Treatment. Permethrin is the treatment of choice. It has not been proven safe in infants younger than 2 months, or in pregnant or lactating women, therefore precipitated sulfur ointment is used for 3 nights. All household contacts should be treated. Treat pruritus with appropriate antihistamines, and secondary dermatitis with appropriate corticosteroids.

F. Follow up. Treatment failures, usually secondary to noncompliance, improper application of scabicide, or reinfection.

G. Complications. Secondary atopic dermatitis and bacterial infection.

H. Education. Proper application of scabicide. Mites can survive for 2 to 5 days on inanimate objects such as clothing and stuffed animals. Proper laundering should be taught.

VIII. LYME DISEASE

A. Etiology and occurrence. A systemic infection caused by the spirochete,

Borrelia burgdorferi.

Successful transmission requires 48-72 hours. It is found in the northeastern and midwestern United States, and can occur in any season, although most prevalent during the warmer months.

B. Clinical manifestations. Flulike symptoms including malaise, arthralgias, headache, fever and chills precede development of the rash.

C. Physical findings. A red macule or papule at the site of a tick bite 2-30 days after infection. The lesions expand to form annular erythematous lesions, generally with central clearing. The center of the lesion becomes darker, vesicular, hemorrhagic, or necrotic. Common sites are thigh, groin, trunk, and axilla.

D. Diagnostic tests. History, including exposure to tick bite, is important. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Western blot analyses for

B. burgdorferi

are recommended by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

E. Differential diagnosis.

Tinea corporis

, urticaria, granuloma annulare, erythema annulare.

F. Treatment. Doxycycline 100 mg 2 times/day for 21 days, amoxicillin 500 mg 3 times/day for 21 days, ceftriaxone 500 mg 2 times/day for 21 days; azithromycin or erythromycin are second-line treatments for pregnant patients or those unable to tolerate above treatments.

G. Education. Educate patients on proper use of insect repellents, and to wear long pants, socks, and long-sleeved shirts in endemic areas.

IX. ROCKY MOUNTAIN SPOTTED FEVER

A. Etiology and occurrence. Rocky Mountain spotted fever, a prototype for all tick-borne spotted fevers, is caused by

R. rickettsii.

It occurs primarily in the southeastern and south central United States. All ages are susceptible; however, it is most common in children younger than 15 years of age. The incidence is highest in mid-summer, and lowest in winter.

B. Clinical manifestation and physical findings. A history of tick bite is common in more than 80% of cases. A prodrome of low-grade fever, headache, malaise, joint or muscle pain, and anorexia may precede the illness, which is sudden, consisting of sweating, chills, severe aches, vomiting, and diarrhea. The most common clinical findings are rash, edema, and fever. The rash may appear soon after the onset of symptoms, first on the ankles and feet, and spreading to the wrists, hands, trunk, and head. Discrete, rose-colored macules, blanching on pressure, soon become popular or purpuric. The resolving rash may desquamate with resulting hyperpigmentation. Nonpitting edema is frequent, with periorbital edema common in children. Conjunctivitis, pharyngitis, photophobia, CNS symptoms including confusion, delirium, seizures, and coma are common.

C. Diagnostic tests. Generally no rise in antibody titer is detected until the second week of the disease. An enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay if IgM and IgG to

R. rickettsii

is sensitive and specific is indicated. Tissue direct and indirect immunofluorescence may identify rickettsiae.

Other books

Trying the Knot by Todd Erickson

Never Run From Love (Kellington Book Four) by Driscoll, Maureen

Duke of Deception (Wentworth Trilogy) by Smith, Stephie

The Duke's Marriage Mission by Deborah Hale

Listen to the Mockingbird by Penny Rudolph

Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf

Sour Puss by Rita Mae Brown, Michael Gellatly

Husband by the Hour by Susan Mallery

A Series of Unfortunate Events: The Carnivorous Carnival by Lemony Snicket

Deadly Accusations by Debra Purdy Kong