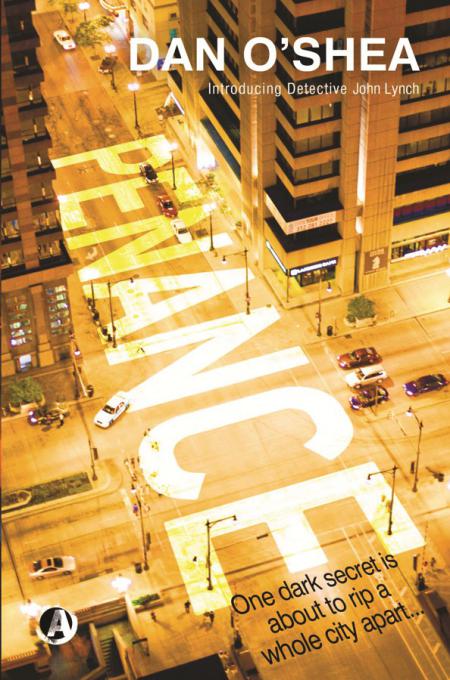

Penance: A Chicago Thriller

Read Penance: A Chicago Thriller Online

Authors: Dan O'Shea

Dan o’Shea

PENANCE

For my father, Dr Thomas A. O’Shea, who raised me in a house lousy with books.

I wish you’d been around to see this one, Dad.

Cast of Characters

The cops (and friends)

1971

Declan Lynch – Chicago police detective

Robert Riordan – Head of the Red Squad

Present Day

John Lynch – Chicago police detective, son of Declan Lynch, nephew of Rusty Lynch

Shlomo Bernstein – Chicago police detective

Harold Starshak – Chicago police captain, Lynch and Bernstein’s CO

Darius Cunningham – Chicago police SWAT sharpshooter

Brian McCord – Medical examiner

Liz Johnson – Chicago

Tribune

reporter

Tribune

reporter

The Politicians

1971

David Hurley, Sr – Mayor of Chicago

David Hurley, Jr– Hurley’s son, Cook County DA, candidate for US Senate

Brendan Riley – Hurley’s right hand man

Hastings Clarke – David Hurley’s chief of staff and campaign manager

Rusty Lynch – Chicago city councilman, Declan Lynch’s brother

Present Day

David Hurley III – Mayor of Chicago

Hastings Clarke – Politician

Rusty Lynch – Retired politician, John Lynch’s uncle

Paddy Wang – Power broker

Tommy Riordan – Chicago political hack, son of Robert Riordan

The Spooks

1971

Zeke Fisher – US intelligence operative

Present Day

Ishmael Fisher – InterGov operative

Colonel Tech Weaver – Head of InterGov, a US black ops group

Ferguson – InterGov operative

Chen – InterGov operative

CHAPTER 1 – CHICAGO

The pain was bad. Helen Marslovak had not taken her painkillers at lunch, not with confession today. If she took her pills, she’d be groggy. Confession was important now. She needed her head clear for that. But now the pain was bad.

She shivered inside her coat as she stepped out the side door of Sacred Heart and stopped to evaluate the stairs. They were dry, at least, but it was cold. (She was always cold now, the cold maybe the worst thing about the cancer, worse sometimes than even the pain.) The cold seemed to make the railing slippery – or maybe it was just her hands, she wasn’t sure.

And then there was a hole in time. She had just picked up her right foot to take the first step and had a firm grasp on the railing and now she was on her back, head facing down, her legs pointing up the stairs. She felt the bite of the wind as her coat and her skirt rode up her legs. Not ladylike, she thought. And she must have wet herself because something warm and wet was running up her back. Something was wrong, her legs wouldn’t move. But she was tired, and even colder, and she thought she would just lie here for a moment before she tried to pull herself up. Maybe someone would come along to…

Nearly half a mile away, Ishmael Leviticus Fisher slid a long green duffle into the back of a rusted Ford 150 and closed the lid on the truck cap. As he pulled away, heading for the expressway, his strong, slender fingers ran over the worn wooden beads of his rosary with practiced precision. The Sorrowful Mysteries.

Detective John Lynch tried to remember the last time he’d been to Sacred Heart. The church was just west of Narragansett, a mile or so south of Belmont. Not quite in Coptown proper – that northwest corner of the city near Niles and Park Ridge that was full of cop families, fireman families. Close enough, though. Streets and Sanitation guys probably. CTA guys.

He’d been down to Sacred Heart during his marriage for sure. He remembered fighting in the car with Katie heading to one of the weddings on the Slavic side of her family. There was a mess of them in Sacred Heart. Summertime, back in 86. Neither of them bothering with being civil anymore, both of them knowing the marital jig was pretty well up, just trying to get their licks in before the bell. It was August that year when the drunk kid in the Trans Am made the whole divorce thing moot, picking off Katie’s Civic on the Kennedy at 2.00am one Saturday morning. Lynch was working third shift, Wentworth. Never did find out where she’d been, what she was coming home from.

Sacred Heart was long with a steep slate roof, brown brick, running east to west. Main door faced west, a glassed-in vestibule with a side door faced south. Rose window over the vestibule, four tall stained glass windows down the side.

Lynch had been to his share of cop funerals, starting with his father’s when he was ten. The cluster of uniforms on the steps at the side door of the church brought that back as he nosed the brown Crown Victoria into a handicapped spot at the end of the walk. Same weather as then, low March sky with all the gray charm of a wet basement floor. He remembered arriving at the church the morning of his father’s funeral, awkward in the new suit, his mom and sister in black, all the uniforms milling around. And then the honor guard forming up, the Emerald Society in front with the bagpipes, six guys in their dress blues taking the coffin from the hearse, Lynch still not quite believing that it was his dad in there, that he was never coming back. Sitting through the service, watching his mom stiffen as the mayor got up to give the eulogy, turning Declan Lynch into an icon Lynch had never known, feeling something new in the air, like watching a religion being born.

No funeral today, but there was still a body. Lynch shrugged into his leather car coat and climbed out of the Crown Vic. Twinge in the knee, the one that had turned him from a third-round draft choice in Green Bay into a cop. Still six feet one inch, one hundred and ninety-five pounds. Hell, ten pounds under his playing weight.

Sergeant Kowalski was shooing the uniforms away from the steps. Lynch liked to get a fresh read on the stiff before everybody started downloading the whats and whens on him. Liked a minute alone to form his own impressions. Kowalski knew to give him his space. Lynch squatted down next to the body.

The woman was sprawled face-up on the stairs, her head on the bottom stair. Flat, moon-shaped face – Polish, Lynch bet. She looked surprised. Not the first time Lynch had seen that. Lynch had heard a lot about stiffs looking peaceful, but most of them he’d seen looked like they were in pain. The lucky ones looked surprised.

A lot of blood had run down under her head, some catching in the white-gray hair, some pooling on the walk. Entrance wound was center chest, right next to one of the buttons on the coat. No blood there. Lynch knew that the human body was a big, tough, blood-filled balloon. More blood in there than most people think. Five or six quarts – ten pounds or better. When you blow a hole in somebody, the blood comes out and keeps coming out until it clots or the heart stops. No blood on the chest meant the heart had stopped right off, nothing pumped out the front. Looking at the wound, Lynch bet the round had gone right through the heart, at least caught a piece of it.

The blood under the body was just a leak, a combination of the location of the exit wound and gravity. No smearing around the shoulders or the head. She hadn’t thrashed around at all, which people do when they get shot, seeing as how it hurts likes hell, which Lynch knew from experience. She’d been dead when she hit the cement. One smudge just on the edge of the pool of blood, then a footprint on the first step, slight footprint on the third, maybe a smudge on the fifth. Woman’s shoe, right foot, slight heel.

Hair was neat, clothes were clean but not new. They looked big on her, like she had lost weight. Nails trimmed, no polish. Minimal makeup. Old shoes with new heels. Dress had ridden up past her knees. Thick stockings, plain slip. Plain wedding ring. Expensive watch, though. Piaget with diamonds around the face. Smudge of something shiny on her forehead, oil probably. Last rites, Lynch bet.

Lynch looked up at Kowalski. “She looks like shit, Sarge.”

“Getting shot will do that for you,” Kowalski said.

“Beyond that, though. Skin seems loose. Color’s bad. Face looks shrunken.”

Lynch stood up.

“All right, Sarge, what else you got?”

“Here’s what I know. Deceased is Helen Marslovak, seventy-eight, lives four doors down, other side of the street. Looks like a single gunshot to the chest. The priest – he’s up in the church – says she finished confession between 3.00 and 3.05 because he starts at 3.00 and she is always the first customer. He figures she probably said a rosary after, which put her out the door about 3.15. An Agnes Weber – she’s inside with the father – came screaming into the church at, the father is guessing, 3.22, because he looked at his watch as soon as she calmed down enough to tell him that the victim was splattered on the stairs, and then it was 3.24. Including the priest, three people were in the church at the time of the shooting. Nobody heard a thing. Also, looking at the body, this ain’t no contact wound, and judging from the spray – you’ll see we got some bits of this and that up top of the stairs – you’re looking at a round with some velocity. My guess is a rifle, but we’ll let the pocket-protector types work that out. One thing you’re not going to like. The father has handled the body, did the last-rites drill before we got here.”

“Saw the oil.”

“Also, the Weber woman tracked through the blood.”

Lynch nodded. “Just the one shot?”

“Looks like. Got all those windows in the vestibule back there, no holes in those. There’s a wooden chest sort of thing back by the wall. They probably put bulletins and such out after mass. Round looks to have hit there.”

“So one shot center chest, likely a rifle. Purse?”

“Yeah. It was on its side, top step. Not even open. Six bucks and change in the wallet. Driver’s license, Social Security card, no plastic. Hanky, keys, rosary. Bout it.”

“And she’s still got the watch. That looks like a couple of grand anyway.”

“Looks like.”

“All right. Thanks, Sarge,” said Lynch.

Lynch nodded to the crime scene guy, letting him know he could start on the body. “OK I go through here on the right?” Lynch asked.

“Yeah, detective. Close to the wall, OK? Got some shit up here.”

Lynch remembered Sacred Heart as looking old school. Dark wood pews in straight rows facing east, broad middle aisle, ornate altar tucked in an alcove on the east wall, racks of votive candles, big statues. Looked like a church, anyway.

Or had. As he pushed through the double doors, he saw white drywall, burnt-orange carpeting and seat cushions, blonde wood pews in a huge, space-wasting semicircle facing the long north wall, the altar on a half-oval riser sticking out of the wall into the pews and something that looked like a life-sized Peter Frampton in a bathrobe hanging from the ceiling on a Plexiglas cross.

“Jesus,” muttered Lynch.

“Well, it is supposed to be,” said a voice to his left. Lynch turned to find a beefy priest in an old-fashioned button-up cassock. Mid-fifties, Lynch guessed. Gone a little to fat, but judging from the chest and shoulders, some weight work in the guy’s past, and not in the distant past.

“Detective Lynch,” Lynch said, offering his hand.

The priest took it. “Father Mike Hughes. I’m the pastor. Actually, I’m the whole staff at the moment. Well, for quite a few moments, now. Young men today just don’t seem to grasp the allure of the collar.”

“Probably need a video game.

Priest for PlayStation

. Kicking the devil’s ass for him.”

Priest for PlayStation

. Kicking the devil’s ass for him.”

“I’ll suggest that to the cardinal.”

Lynch and the priest sat at the end of one of the pews.

“Comfy, with the cushion and all,” said Lynch.

The priest smiled. “The church was remodeled in the late Eighties. While the liturgical remedies of Vatican II were long overdue, some of the resulting architectural excesses have been less than fortunate.”

“Ms Marslovak like it much?” said Lynch.

“No, I doubt that she did. But you wouldn’t hear it from Helen. The woman would never breathe a word against the church.”

“Know her well?”

“I’ve been here twelve years. She’s been at mass every morning, and I do mean every morning. First in for confession every Friday at 3.00pm sharp. Past president of the St Anne’s unit. Tends the garden. Cooks me a roast first Sunday of every month, God bless her soul.”

“So no reason you can think of for someone to kill her?”

“No, none.”

Lynch sat for a moment. “Look, Father, you were the last person to talk to her. Anything in that conversation that might shed some light here?”

“You mean in her confession?” The priest turned toward Lynch. “Irish boy in a town like this, you’ve got to be Catholic, right?”

“I don’t know how often you’ve got to get your card renewed. It’s been a while.”

“Baptized, though?”

“Oh yeah. St Lucia’s, 1961.”

“Once you’re dipped, you’re ours for life. And you know the rules. If it’s said in confession, it stays there. That secret doesn’t just go to her grave, it goes to mine.”

“I figured,” said Lynch. “Just taking a shot. She have family in the parish?”

“Her husband died three years ago. ALS. Long time going. She’s got a son, but he lives up on the north shore. Lake Forest, I think. Eddie Marslovak? MarCorp?”

Lynch nodded. “That’s where I’ve heard the name. They close?”

The priest shrugged. “She loved him, but she didn’t approve of him. A couple of divorces, professed agnostic. He’d visit, I know, and they talked. But close? I don’t know.”

“How about after the husband died. Any gentlemen friends?”

The priest chuckled. “If you knew Helen, detective, you would know how funny that is. No.”

“Other friends?”

“Helen was something of an institution, volunteered at the school, helped with everything, really. Gave free piano lessons. Taught CCD for thirty-some years.”

“You’re not giving me much to work with here. Listen, Father, looking at her, she didn't look well. Was she sick, do you know?”

The priest paused for a moment. “I hear some things in confidence but not necessarily in confession. Yes. Helen was very sick. Cancer. She was dying. She didn’t want anyone to know, not even her son. She said it was her cross, and she was pleased to bear it. There are elements of this that we discussed in confession that I cannot share with you. But she did talk to me about funeral arrangements. So that she was ill, was dying, that I can tell you.”

“This stuff you can’t tell me, anything in that?”

“Detective, I cannot divulge or even hint at what is said within the seal of confession.”

Lynch looked at the priest, but the priest was looking away.

Agnes Weber was just this side of shock. Probably close to Marslovak’s age. She was holding a pair of long black gloves, absentmindedly wringing them.

“Mrs Weber? I'm Detective Lynch. Can I talk to you for just a minute here? Then we can get you home.”

She nodded slightly, not looking up, still wringing the gloves. “This is so horrible, so horrible.”

“It is, Mrs Weber, and I am very sorry. You knew Mrs Marslovak?”

“Helen? Everybody knew Helen. She was... she was... just so decent to everybody. I lived across from her, just across and one house up. I’ve known Helen for thirty-five years.”

“She sounds like a wonderful woman. The father was telling me.”

“I can’t understand this.” Sounding puzzled, and a little angry suddenly.

“Mrs Weber, how did you get to the church today?”

“Oh, I walked. I always walk. I don’t like to drive anymore. It’s not far.”

Other books

Side Chic 2 (A Ratchet Mess) by West, La'Tonya

Cold in Hand by John Harvey

Finding 52 by Len Norman

VINA IN VENICE (THE 5 SISTERS) by Kimberley Reeves

Nothing to Lose by Alex Flinn

Fallen Embers (The Alterra Histories) by C. S. Marks

Moon Princess by Barbara Laban

Dead in the Water by Robin Stevenson

Rebecca's Tale by Sally Beauman

Prospero's Children by Jan Siegel