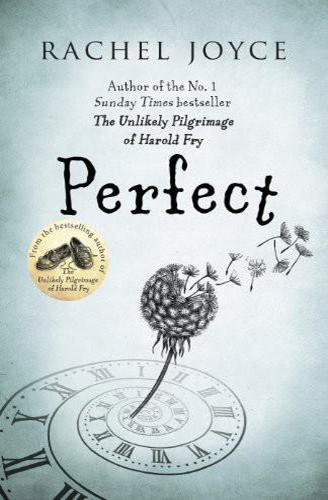

Perfect

Authors: Rachel Joyce

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Contemporary, #Contemporary Fiction

In 1972, two seconds were added to time. It was in order to balance clock time with the movement of the earth. Byron Hemming knows this because James Lowe has told him and James is the cleverest boy at school. But how can time change? The steady movement of hands around a clock is as certain as their golden futures.

Then Byron’s mother, late for the school run, makes a devastating mistake. Byron’s perfect world is shattered. Were those two extra seconds to blame? Can what follows ever be set right?

Contents

4: Things That Have to Be Done

13: The Catching of a Goose Egg and the Losing of Time

For my mother and my son Jo

(without an ‘e’)

Only when the clock stops does time come to life.

William Faulkner,

The Sound and the Fury

The Addition of Time

I

N 1972, TWO

seconds were added to time. Britain agreed to join the Common Market, and ‘Beg, Steal Or Borrow’ by the New Seekers was the entry for Eurovision. The seconds were added because it was a leap year and time was out of joint with the movement of the Earth. The New Seekers did not win the Eurovision Song Contest but that had nothing to do with the Earth’s movement and nothing to do with the two seconds either.

The addition of time terrified Byron Hemmings. At eleven years old he was an imaginative boy. He lay awake, picturing it happen, and his heart flapped like a bird. He watched the clocks, trying to catch them at it. ‘When will they do it?’ he asked his mother.

She stood at the new breakfast counter, dicing quarters of apple. The morning sun spilled through the French windows in such clean squares he could stand in them.

‘Probably when we’re asleep,’ she said.

‘Asleep?’ Things were even worse than he thought.

‘Or maybe when we’re awake.’

He got the impression she didn’t actually know. ‘Two seconds are nothing,’ she smiled. ‘Please drink up your Sunquick.’ Her eyes were bright, her skirt pressed, her hair blow-dried.

Byron had heard about the extra seconds from his friend, James Lowe. James was the cleverest boy Byron knew and every day he read

The Times

. The addition of two seconds was extremely exciting, said James. First, man had put a man on the moon. Now they were going to alter time. But how could two seconds exist where two seconds had not existed before? It was like adding something that wasn’t there. It wasn’t safe. When Byron pointed this out, James smiled. That was progress, he said.

Byron wrote four letters, one to his local MP, one to NASA, another to the editors of

The Guinness Book of Records

and the last to Mr Roy Castle, courtesy of the BBC. He gave them to his mother to post, assuring her they were important.

He received a signed photograph of Roy Castle and a fully illustrated brochure about the Apollo 15 moon landing, but there was no reference to the two seconds.

Within months, everything had changed and the changes could never be put right. All over the house, clocks that his mother had once meticulously wound now marked different hours. The children slept when they were tired and ate when they were hungry and whole days might pass, each looking the same. So if two seconds had been added to a year in which a mistake was made – a mistake so sudden that without the two seconds it might not have happened at all – how could his mother be to blame? Wasn’t the addition of time the bigger crime?

‘It wasn’t your fault,’ he would say to his mother. By late summer she was often by the pond, down in the meadow. These days it was Byron

making the breakfast; maybe a foil triangle of cheese squished between two slices of bread. His mother sat in a chair, chinking the ice in her glass, and slipping the seeds from a plume of grass. In the distance the moor glowed beneath a veil of lemon-sherbet light; the meadow was threaded with flowers. ‘Did you hear?’ he would repeat because she was inclined to forget she was not alone. ‘It was because they added time. It was an accident.’

She would put up her chin. She would smile. ‘You’re a good boy. Thank you.’

It was all because of a small slip in time, the whole story. The repercussions were felt for years and years. Of the two boys, James and Byron, only one kept on course. Sometimes Byron gazed at the sky above the moor, pulsing so heavily with stars the darkness seemed alive, and he would ache – ache for the removal of those two extra seconds. Ache for the sanctity of time as it should be.

If only James had never told him.

Inside

1

Something Terrible

J

AMES

L

OWE AND

Byron Hemmings attended Winston House School because it was private. There was another junior school that was closer but it was not private; it was for everyone. The children who went there came from the council estate on Digby Road. They flicked orange peel and cigarette butts at the caps of the Winston House boys from the top windows of the bus. The Winston House boys did not travel on the bus. They had lifts with their mothers because they had so far to travel.

The future for the Winston House boys was mapped out. Theirs was a story with a beginning, a middle and an end. The following year, they would take the Common Entrance exam for the college. The cleverest boys would win scholarships and at thirteen they would board. They would speak with the right accent and learn the right things and meet the right people. After that it would be Oxford or Cambridge. James’s parents were thinking St Peter’s; Byron’s were thinking Oriel. They would pursue careers in law or the City, the Church or the armed forces, like their fathers. One

day they would have private rooms in London and a large house in the country, where they would spend weekends with their wives and children.

It was the beginning of June in 1972. A trim of morning light slid beneath Byron’s blue curtains and picked out his neatly ordered possessions. There were his

Look and Learn

annuals, his stamp album, his torch, his new Abracadabra magic box and the chemistry set with its own magnifying glass that he had received for Christmas. His school uniform had been washed and pressed by his mother the night before and was arranged in a flattened boy shape on a chair. Byron checked both his watch and his alarm clock. The second hands were moving steadily. Crossing the hall in silence, he eased open the door of his mother’s room and took up his place on the edge of her bed.

She lay very still. Her hair was a gold frill on the pillow and her face trembled with each breath as if she were made of water. Through her skin he could see the purple of her veins. Byron’s hands were soft and plump like the flesh of a peach but James already had veins, faint threads that ran from his knuckles and would one day become ridges like a man’s.

At half past six, the alarm clock rang into the silence and his mother’s eyes flashed open, a shimmer of blue.

‘Hello, sweetheart.’

‘I’m worried,’ said Byron.

‘It isn’t time again?’ She reached for her glass and her pill and took a sip of water.

‘Suppose they are going to add the extra seconds today?’

‘Is James worried too?’

‘He seems to have forgotten.’

She wiped her mouth and he saw she was smiling. Two dimples had appeared like tiny punctures in her cheeks. ‘We’ve been through this. We keep doing it. When they add the seconds, they’ll say something about it first in

The Times

. They’ll talk about it on

Nationwide

.’

‘It’s giving me a headache,’ he said.

‘When it happens you won’t notice. Two seconds are nothing.’

Byron felt his blood heat. He almost stood but sat back again. ‘That’s what nobody realizes. Two seconds are huge. It’s the difference between something happening and something not happening. You could take one step too many and fall over the edge of a cliff. It’s very dangerous.’ The words came out in a rush.

She gazed back at him with her face crumpled the way she did when she was trying to work out a sum. ‘We really must get up,’ she said.

His mother pulled back the curtains at the bay window and stared out. A summer mist was pouring in from Cranham Moor, so thick that the hills beyond the garden looked in danger of being washed away. She glanced at her wrist.

‘Twenty-four minutes to seven,’ she said, as if she were informing her watch of the correct time. Lifting her pink dressing gown from its hook, she went to wake Lucy.