PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk (27 page)

Read PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk Online

Authors: Sam Sutherland

Everyone in the Action was broke, and everyone in the Action was high. They fell apart as soon as they got back to Ottawa.

The Bureaucrats were like the Action’s geeky kid brother, less prone to grandiose tales of debauchery and talking shit with Dee Dee Ramone, and more likely to be in the basement on a Friday night learning how to play every song on

The Nerves

note for note. There was no coke and no groupies. There were no shady record deals, and no talk of tours with the Stranglers. But for what it’s worth, the discovery of the Bureaucrats remains my favourite of this entire project.

They were never a major touring band, and their material is hard to track down. “Feel the Pain,” one of their best songs, is led by a hook every bit as good as “Hanging on the Telephone,” and I have no trouble believing that Blondie probably would have covered their songs, too, if they just lived a few hours south. They represent the kind of aggressive minimalism that made early records by the Clash and Wire so compelling, and possess the same coiled-snake attitude that doesn’t age over time. Their style sounds as fresh today as it did 30 years ago, which is rare. When you consider the sheer number of new songs I heard compiling this book, I hope you’ll understand why me saying that “Feel the Pain” is the best song I uncovered isn’t an unnecessary personal detail I offer lightly. It’s an unnecessary personal detail that, I hope, will encourage anyone reading this to track down the band’s complete discography and turn them into belated Grey Cup halftime show performers, like a come-from-behind Blue Rodeo or BTO. But a power-pop band.

The band played their first show at the School of Architecture at Carlton University, a gig booked by their manager (read: friend who couldn’t play an instrument), Carlton student David Whales. The energy was strange; it was a Friday the 13th, the day after Nancy Spungen’s apparent murder at the hands of her boyfriend, punk’s most famous junkie, Sid Vicious. Engineering students provided the security and everyone acted as self-consciously “punk” as possible.

“I think it ended in a riot, if I’m not mistaken,” says vocalist and guitarist Joe Frey. “I think I remember things being thrown. It was pretty funny, in retrospect.”

“I feel like a lot of people’s first shows ended in riots at that time,” I tell him.

“Yeah, there was a weird energy. I think a lot of the audience thought that it was about jumping up and down in front of a band and throwing things at them and spitting on them.”

“I was a social leper at school the next day because I’d brought punk to the School of Architecture,” concludes David Whales.

Things improved from their first pseudo-riot, and by the time they had rehearsed enough to feel ready for a second show, the Rotters Club had opened. Frey remembers the club as “dark and stinky” and the band’s first few shows as “very shaky,” but admits that, after a few duds, they finally began to improve. By the end of ’79, the Bureaucrats were ready to make the trip to Larrimac and record at the Rotters offshoot studio, Double Helix. Since none of the bands ever had enough money to pay for recording, a deal was worked out where they would receive a lower cut of the door at their shows in exchange for time at the studio. It was a relationship that worked for everyone, since the door money wasn’t about to make anyone rich, and it left the Ottawa scene with a remarkably strong catalogue of original recordings. Double Helix wasn’t just a cheap basement operation; it was a cheap basement operation that cared, and many of the recordings produced there sound leagues better than anything that came out of bigger cities like Toronto. And the Bureaucrats’ first single is among the best.

With an increasingly proficient live show and a freshly pressed 45, the band decided to hit the road, touring regularly to Montreal and Toronto, filling dates with lunchtime high school gigs in between.

“We played one of those strange daytime shows, and all I remember is all the girls screaming like it was the Beatles,” says Whales. “They all ran up to the front and all the teachers were trying to stop them. To see that it was like, ‘God, are they insane? It’s just the Bureaucrats, not the Beatles.’ But it was fun to watch. And the teachers were suitably flustered and unhappy.”

The band’s van required constant work, with members frequently banging pieces back into place on the side of the highway to avoid a catastrophic accident. They played regularly at the Edge in Toronto and the Hotel Nelson in Montreal, but things started to fall apart when half the band began insisting they move to the Big Smoke and try to give the band a serious go.

“I wanted to move things along, and in my mind, Toronto was the next step,” says Frey. “I wanted to get to Toronto and break into the Toronto scene. A few of the other guys were just not into it. They didn’t want to leave Ottawa.” The friction led to the untimely dissolution of the Bureaucrats in 1980. Like many bands of that era, you have to wonder what would have happened if the band had taken the leap and moved to Toronto. Maybe nothing, maybe the halftime of the Grey Cup.

The Red Squares were the strangest act at the centre of the Rotters Club scene. Everyone I meet describes them in a different, often completely contrary way. Their lone single only hints at their utter live weirdness, and I am told numerous times that it is barely representative of the band’s true sound. What is clear is that Ottawa’s scene was an incredibly diverse one, and the Red Squares provide the perfect proof.

“The Red Squares were never really punk,” says Stuart Smith, who played bass in the band when they recorded their first single. “They had a punk attitude, but you had an M.A. in art history in that band. Extremely highly educated, literate people.” That single, “Ottawa Today,” hints at a bizarre mix of classic R&B, psychedelia, and the Talking Heads, but it’s clear that the final product is not what Smith ever intended. The original mix, which had such standard effects applied to it as reverb and compression, was rejected by the band’s singer, who saw fit to remix both songs himself. He had never mixed anything before, and the final product shows it. Even today, Smith is still burned by the way things went down and is insistent that he intends to re-release the songs as he originally mixed them; he’s gone so far as to track down the necessary reel-to-reel equipment and have it delivered to his home. As it stands, the two Red Squares songs in existence are a very weird mix of dry, hardcore-style production and weirdo psychedelic guitars. And not much else is known about the band. Consider this paragraph a warning shot, and an invitation to get the original mixes out, so that the band’s legend can transcend hushed oral tradition and rip through some speakers in the new millennium.

It didn’t take long for the Ottawa scene to outgrow the Rotters Club. With the increasing popularity of local bands, and the steady presence of major Canadian touring acts like D.O.A. and the Viletones, that “dark, stinky” basement was no longer adequate, and Smith moved his punk clubhouse to a proper venue just up the street, the Eighties Club. Suddenly, running the venue was a serious full-time gig that was losing more money than it was making, despite some high-profile bookings. Two key factors led to the demise of the club; primarily, the higher overhead, which made any potential losses, such as a John Cale show booked during a snowstorm, near catastrophic. A minor irritation involved a former Rotters Club employee opening up the old venue under the RC moniker, a hurtful act of insubordination that still irks Smith to this day. Feeling unsupported by the scene he helped to build, Smith cut his losses and moved to Toronto. He bummed around the city for a year before stumbling into real estate, then commercial real estate. And it looks like things have gone pretty well since.

There is a long out-of-print compilation of Rotters Club artists, recorded at Double Helix, called

Rot ’n’ Roll

. Given the calibre of what I’ve heard from first-wave Ottawa bands, this record has been built up in my mind as Ontario’s mythic answer to the legendary

Vancouver Complication

album. When we finish our conversation, Smith tells me I should come over to his place some time and listen to it. I just hope I’m not the only one who gets to experience it in this decade. Consider this my plea to someone to get behind the reissuing of as much Ottawa punk as possible. It might be some of the best music covered in this book.

THE SUBHUMANS

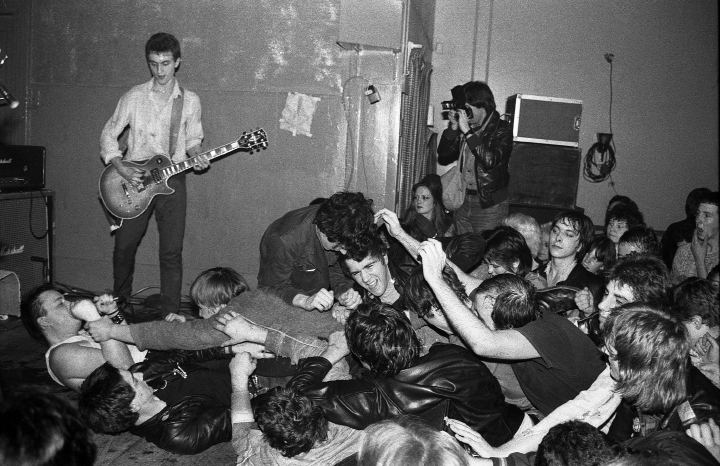

The Subhumans [© bev davies]

January 20, 1983, 9:00 a.m. PST

The cop has his knee pressed deep into Gerry Hannah’s back, pinning him against the asphalt. There’s a gun against his temple, and the thick taste of iron on his lips. Hannah runs his tongue through his mouth while a voice barks at him to get the fuck up. He’s missing a goddamn tooth, knocked out when the cop pulled him out of the truck during what he thought was a routine traffic stop. Only a few kilometres south of Squamish, Hannah had been heading north from Vancouver on the beautiful Sea-to-Sky highway, travelling with the Direct Action group he had fallen in with following his departure from the Subhumans in ’81. DA was wanted for the bombing of the Litton Industries plant in Toronto, the Cheekye-Dunsmuir B.C. Hydro substation, and three adult video stores in Vancouver. All five members were captured that day in a large-scale sting operation that had been in the planning stages for months, ending with a fake construction crew stopping the group en route to their daily training session and target practice in the B.C. forest. Before getting into an unmarked police car at the side of Highway 99, Hannah asks the cop if he can go find his tooth. The cop tells him that the tooth is the least of his worries.

The arrest and prosecution of Gerry “Useless” Hannah happened over two years after the release of the Subhuman’s seminal album

Incorrect Thoughts

and Hannah’s subsequent split from the group. While the rest of the band soldiered on, recruiting Ron Allen, hitting the road, and recording

No Wishes, No Prayers

for SST, they split before its release in 1983, only a few months after Hannah’s arrest. All of which is to say that Hannah’s involvement in domestic terrorism shouldn’t cast a violent pall over the Subhumans. But it does.

Hannah’s arrest galvanized the Vancouver punk scene in a way that still makes discussions about it uncomfortable. Concerned that the explosion of media interest in the story would make a fair trial impossible, bands like D.O.A. and the Subhumans staged benefits for the Squamish Five’s legal defence, referred to in activist circles as the Vancouver Five. In essence, they came out in support of a series of bombings that horrifically injured 10 innocent people in the name of Direct Action’s “propaganda of the deed,” a plan to incite a popular revolt against the evils of the state, weapons manufacturers, and pornographers.

The Litton Industries bombing — which Hannah did not directly participate in, but supported — split open the back of security guard Terry Chikowski by 14 inches, embedding half of a brick and several inches of sheet metal in him “like a shark’s fin.” It snapped four ribs off his spine and blew his diaphragm apart, sending four pounds of muscle flying off his back. It disintegrated his spleen and embedded fragments of glass in his heart, further fragments collapsing his left lung and kidney.

This was the action defended by the Subhumans’ former manager, David Spaner, in the pages of

Maximumrocknroll

. He wrote that “the Five recognize that social change — like rebel music — is not made by professionals or experts; it’s made by ordinary people taking control of their lives and acting against racism, sexism, nuclear weapons, authority, and the other terrors of everyday life.” It was the action tacitly supported by “Free the Five” concerts featuring bands like the Dead Kennedys. It was the action continually supported by Gerry Hannah, who wrote to

Maximumrocknroll

from prison that “It’s good to know that there are many people out there that genuinely care about our current situation and support us as political people engaged in resistance against the state.”

Hannah, who was planning to rob a Brink’s truck with stolen automatic weapons when he was arrested, was sentenced to 10 years in prison and served five. In the documentary about his release from prison,

Useless

, he is shown burning his parole card, along with the card for his parole officer, Bob Reading. “So long, Bob,” he says, while the crowd around him shouts, “Burn, Bob!” The viewer is not left with the impression that prison had much of an effect on Hannah.

“We pretty much came out totally supporting Gerry and the Vancouver Five,” says Brian Goble, the Subhumans’ vocalist. “I don’t think we gave it much thought, but there wasn’t anywhere else we could really throw our support.” In 2005, the Subhumans, with Gerry, reunited. And no one really likes to talk about the bombing, Direct Action, or prison.

“I made a decision when I got involved with punk rock,” says Hannah, who’s seated on the back patio of a Toronto bar with his bandmates. “I would not be playing punk rock when I was 26. I decided part of the idea was to usurp the dinosaurs that were still trying to play rock music. And by the time I was 26, I guess I wasn’t playing because the band had broken up. But somewhere along the line, my thinking changed.”

In 1977, the Skulls, Vancouver transplants trying to break into what they perceived to be a more promising punk scene in Toronto, were without an opening band. Their friend and makeshift roadie, Gerry “Useless” Hannah, had been trying his hand at writing punk songs, having only recently warmed to the genre. He used to sing in a very early, very jam-y version of the Skulls, alternatively billed as the Resurrection and the Icon, when the band lived in the British Columbia woods without electricity and were basically nothing but a bunch of dirty, long-haired hippies. The band had initially resisted the first warning shot from the worldwide punk cannon, tentatively working Ramones covers into a set that leaned heavily on ’70s arena rock.

“I wasn’t sure whether I liked that first Ramones record all that much at first ’cause it was so different from anything else I’d heard up to that point,” recalls Goble. “

The Idiot

by Iggy Pop was floating around, and a few Bowie numbers were kind of on the punk edge. It was a transition period for me.” The Skulls may have debuted with a Beatles cover at a logger’s wake in Cherryville, B.C., but they soon found themselves immersed in the new sounds of New York and London, a long way from home and with substantially shorter haircuts. And in need of an opening act.

The Skulls switched up their instruments and handed Hannah a bass, dubbing themselves Wimpy and the Bloated Cows. Fronted by Skulls’ bassist Brian “Wimpy Roy” Goble and featuring Ken “Dimwit” Montgomery on guitar and Joe Keithley behind the kit, the band was a joke, a fuck band in the classic Vancouver model, born of necessity and taken seriously by absolutely no one. It was an oddly prophetic joke project. According to Goble, they only ever played the one show in Toronto, and soon after, the Skulls split and splintered.

“Toronto?” he asks. “My perception was it was kind of arty. It had more roots, and it already had some established bands that were pretty big draws. The crowds didn’t feel all that welcoming to a bunch of west coasters. I mean, there were some nice people, but I don’t think we ever felt like we were that welcome there.” After the band’s failed Ontario experiment, Keithley and Goble spent some time in London, while the rest of the band headed home to Vancouver.

Back on the west coast, two bands formed, then fused like a filthy punk Voltron — the Stiffs, which featured Hannah and a promising guitarist named Mike Graham (plus two friends named Sid Sick and Zippy Pinhead), and the Subhumans, with Goble, Montgomery, and former Skulls guitarist Brad Kent, an influential force in the band’s social circle who had opted to stay in Vancouver during the group’s great eastern migration. It’s worth noting that Pinhead’s father was the head of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Christian Association. “So you can imagine how disappointed he was in his boy,” laughs D.O.A.’s Joe Keithley. “But that’s the way it goes, right?”

“We just said, ‘You should get rid of Zippy and Sid and come play with us,’” laughs Goble. Soon, Kent decamped to D.O.A. with Joe Keithley, and the first classic Subhumans lineup was born. It wasn’t long before the group had already fashioned a lean set of acerbic punk tunes, hitting the studio to record their first two songs, “Death to the Sickoids” and “Oh Canaduh.” The single remains a classic of the era, with the latter song regularly covered by acts ranging from Nomeansno to Andrew W.K., and the former an untouchable piece of early punk perfection. The band managed to combine the coming onslaught of the first wave of hardcore with the melodic sensibility of new wave; their time in the arena rock trenches of Cherryville had given them a naturally epic tendency, balanced by a blackly humorous side that continued to shine through even their darkest political songs. Unlike many of their American hardcore peers, an ability to wink at the firing squad defined the Vancouver scene, and the Subhumans in particular.

“Even thought it’s hardcore music, it’s still funny,” says the Pointed Sticks’ Nick Jones. “I think that was something that we valued a lot in Vancouver. We weren’t doing this for the money, and we certainly weren’t doing it for the recognition. We were doing it because we wanted to have a good time. If you’re taking it that seriously, then it wasn’t really going to be worthwhile to us.”

Almost immediately, the Subhumans were at the top of Vancouver’s growing punk heap, forming a dangerous hardcore one-two punch with D.O.A. Soon, it was them, and the Pointed Sticks, who became the ambassadors of the west coast’s dedicated, aggressive, and varied new sound. The Subhumans’ first single was the ideal first strike, portending the invasion of west coast hardcore throughout North America with its streamlined sound and pseudo-political musing. There was also the undeniable appeal of drummer Ken Montgomery, whose massive size behind the kit translated to massive sounds on tape. But that doesn’t mean the band thought they were any good.

“It was a pretty unsatisfactory recording session,” says Goble. “We were totally green at that point, didn’t know anything about studio stuff at all. I remember wasting a lot of time on stupid details. I had a terrible vocal performance and, I don’t know, the whole thing sounds like it was played under a blanket.” It’s the second time I’ve talked to Goble. This time, he’s on the phone in his car, pulled over on Main Street in Vancouver while trying to avoid rush hour traffic. I chalk up his general dismissal of numerous Subhumans classics to context.

“The Subhumans had a whole different sound and style,” says the Modernettes’ John Armstrong. “I think it was because they were left alone. There was no music industry here. It was really only about Trooper and Prism, bands that came out of the club circuit and were aiming at top 40 success. Satin pants, poofy hair. That was the only music industry there was.”

Which is not to say that Vancouver musicians were without ambition. Despite a dedicated fanbase inside the city’s growing punk community, Montgomery quit soon after the band’s first recording to join the Pointed Sticks. Goble maintains that Montgomery may have been the most career-minded of the group, and he saw the poppier sound of the Sticks as a more likely route to a future as a professional drummer. All in spite of the slightly odd coupling of the hulking Montgomery with the teen idol Sticks.

“I don’t think he really fit in well with the Pointed Sticks,” says Goble. “They’re kind of like an English, gentlemanly pop band, and then you’ve got this big gorilla-like figure in the back that plays thundering drums.” The band didn’t want for long, however, when Koichi Imagawa, better known locally as Jim, stepped in to fill the gorilla’s big shoes. Looking to produce a new recording to show off their still-developing sound, the band hooked up with Quintessence Records and Bob Rock at Little Mountain Sound, a pairing that had started with the Modernettes and Young Canadians.

With each member of the band developing a distinct voice as a songwriter, the band’s eponymous 1979 12" benefitted from equal input from Hannah, Goble, and Graham. It boasts one of the band’s defining anthems, “Fuck You,” alongside the tongue-in-cheek skewering of macho sexism with “Slave to My Dick,” and the dark, raging finger-pointing of “Death Was Too Kind.” Even more so than with their first single, the Subhumans now embodied the emerging sound of west coast hardcore, ahead of their time and cited as a major influence throughout the ’80s accordingly. No Canadian punk mix tape is complete without “Fuck You,” its distilled anger and agro-as-fuck minor chord changes still stirring up adolescent angst decades after its release. It was broad-based teenage finger-raising of the kind later popularized by bands like Rage Against the Machine and rappers like Eminem, but grimmer, and, in some ways, even more potent.

Even years removed from its production, Goble admits that he’s still happy with how the recording sounds. With a satisfactory batch of songs and the support of the city’s lone punk label, the Subhumans followed their peers D.O.A. out into the North American touring void, becoming one of the first Canadian punk bands to travel across the country and down into the United States. Like many Vancouver bands, the Subhumans felt an immediate kinship with the city of San Francisco, exemplified by their continued relationship with Jello Biafra’s Alternative Tentacles label, which has released all the band’s post-reunion material.

“It was obviously a lot of fun, y’know?” says Goble of the band’s experience in California. “I liked the environment. San Francisco seemed like a really cool place, a little more mature than Vancouver. Better pinball machines. And you could walk into any store and get beer.”

At some point in their cross-continental adventures, the band found themselves re-recording the fan favourite “Fuck You,” a song with, unsurprisingly, several crucial, emphatic swears in its chorus. Problematically, the band was working in a Christian recording studio.

“When they were recording the vocals, someone else in the band would just yell something every time they said fuck,” laughs John Armstrong, who spent a few weeks on the road with the band during the Modernettes’ heyday. “By the time mixing happened, it was pretty chaotic.”

Before long, the band had amassed enough songs and fans to justify a full-length, still a rare high water mark for many first-wave punk bands. On the strength of their first two releases, the Subhumans had already cemented a place in the annals of hardcore history. But it was in 1980 with the release of

Incorrect Thoughts

that they became true punk legends, a band with an album capable of going toe to toe with any other record of the era. It was one of the strongest debuts of the decade, from a punk band or otherwise.

Incorrect Thoughts

, from the anthemic call to arms of opener “The Scheme” through to the sludgy sarcasm of the last song, “Let’s Go Down to Hollywood (And Shoot People),” put all the Subhumans’ power into nearly 45 minutes of music.